This fantastic case and post was written by Jesse McLaren (@ECGcases), edited by Smith

Case

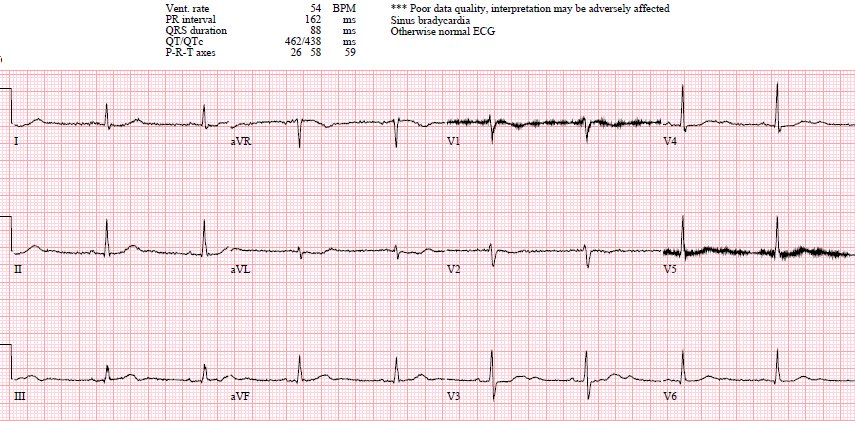

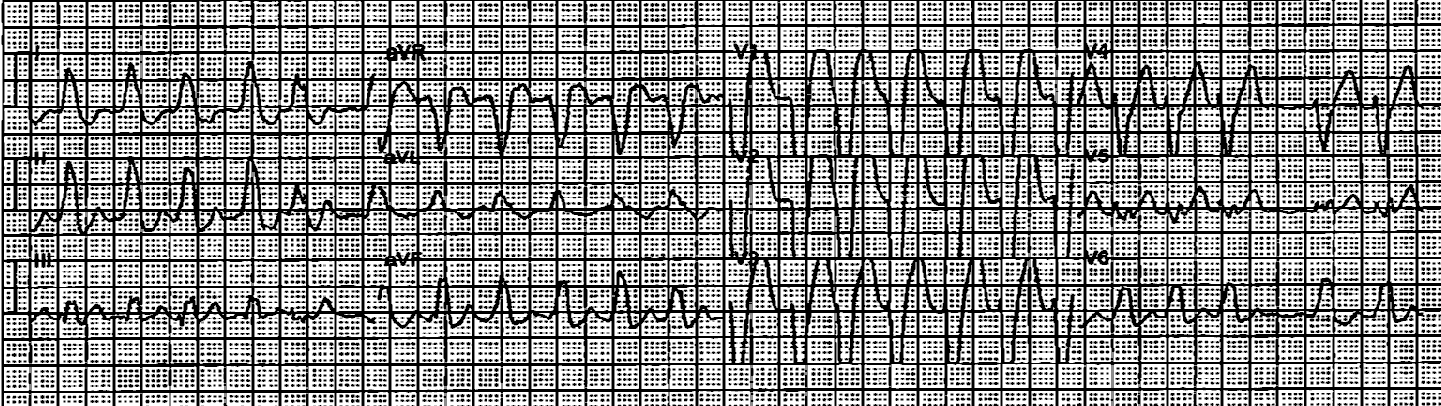

You’re shown an ECG from a patient in the waiting room with

chest pain.

What do you think?

Sinus bradycardia, normal conduction, normal axis, normal R

wave progression, no hypertrophy. There’s primary ST depression in the

precordial leads maximal in V3-4, and an inverted T wave in V2. There’s also a down-up

T wave in aVL with a tiny bit of ST depression (which suggests inferior MI), but without associated inferior findings.

Step 1 to missing posterior MI is relying on the STEMI

criteria. A prospective validation of STEMI criteria based on the first ED ECG

found it was only 21% sensitive for Occlusion MI, and disproportionately missed

inferoposterior OMI.[1] This ECG is STEMI negative, but the emergency physician

was concerned about posterior OMI based on primary ST depression in the

anterior leads—so the patient was immediately brought into a room to be seen.

It was a 60yo with a history of stents to the circumflex and

right coronary arteries, who presented with 9 hours of fluctuating central

chest pain. In the past two hours it increased in intensity and became constant,

radiating to the neck and bilateral arms, associated with shortness of breath

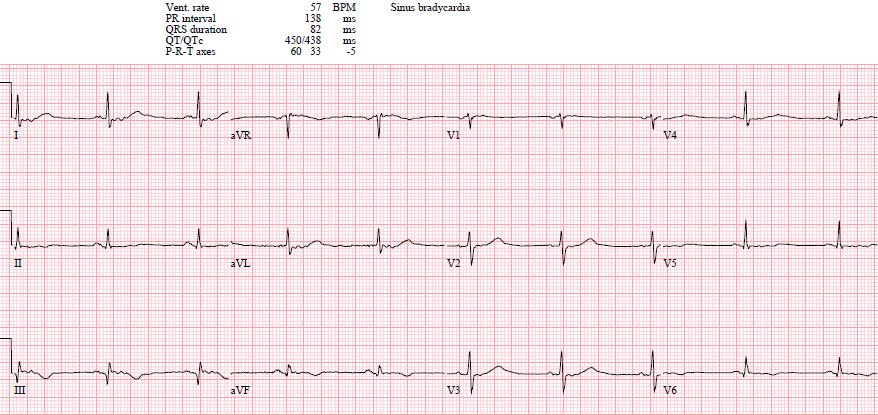

and vomiting, and persisted despite taking nitro. Below is the old ECG:

The old ECG is normal, confirming that the anterior ST

depression is new and the patient has posterior OMI until proven otherwise.

The old one also shows flatter T-waves than the new one (are then normal appearing T-waves in inferior leads really larger than they should be?)

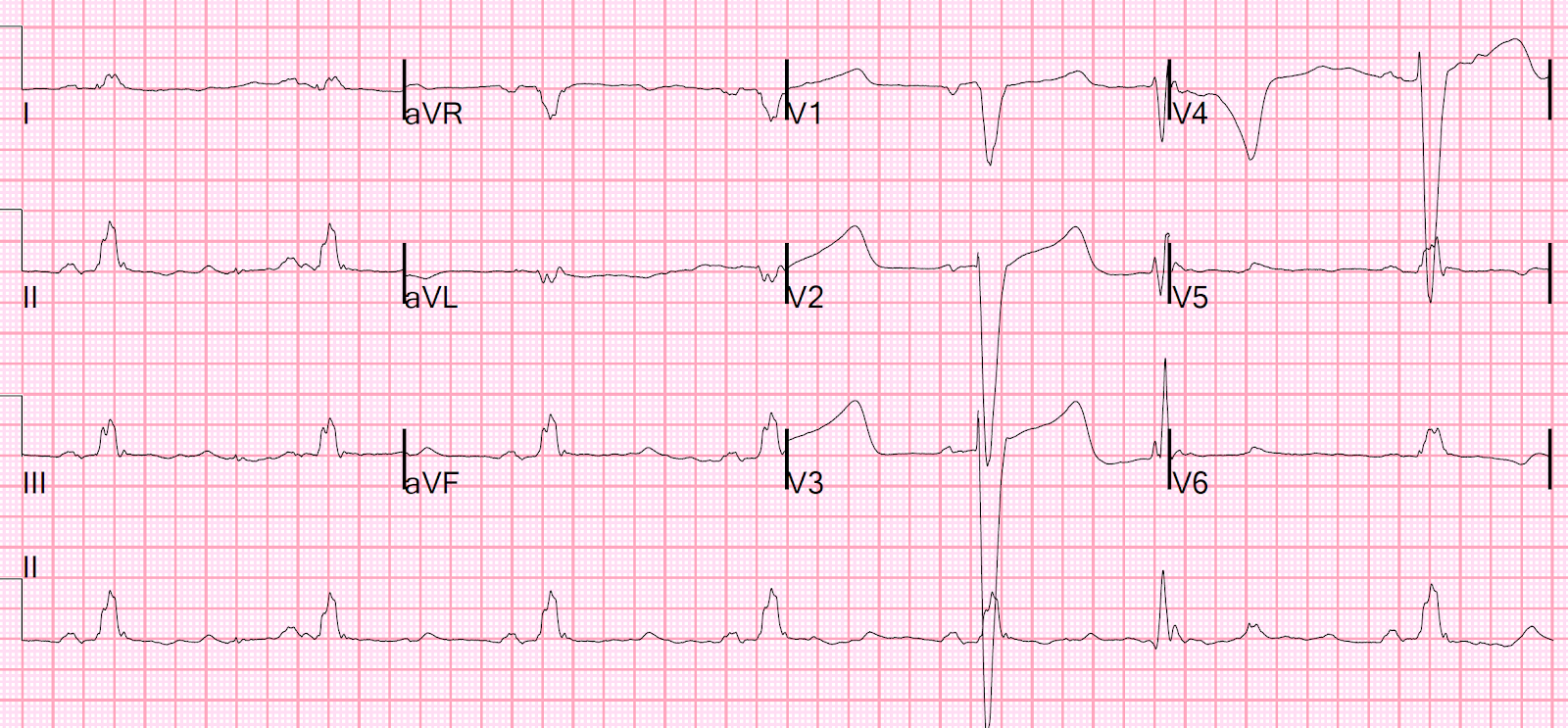

A

15 lead ECG was done (below).

This is Step 2 to missing posterior OMI: assuming (based

on the STEMI paradigm) that it has to have ST elevation on the posterior leads.

But posterior leads have tiny voltages with minimal ST elevation: STEMI

criteria only requires 0.5mm ST elevation in one posterior lead, and this can be falsely negative. As

Meyers/Smith recently demonstrated, primary ST depression isolated to the

anterior leads, even if less than 1 mm, is diagnostic of posterior OMI even without posterior leads.[2]

Here there is no posterior ST elevation, but the anterior ST depression is also less—so it is dynamic, confirming acute ischemia. But it is

still STEMI negative.

This demonstrates why, if you are going to record posterior leads, you must keep V1-V3 leads in place. The absence of STE in V7-V9 is often due to resolution of ischemia, as seen by resolution of ST depression in V7-V9.

Step 3 is not recognizing STEMI(-)OMI, which comprise 40% of

occlusions and are associated with significant and preventable delays to

reperfusion.[3] While this patient had a high pre-test probability, presented

with ongoing chest pain and had dynamic ECG changes diagnostic of posterior

OMI, there was no ST elevation on either anterior or posterior leads. But the

emergency physician was still concerned about a STEMI(-)OMI, so gave aspirin and

more nitro and called for a stat cardiology consultation—specifically citing

concerns of posterior OMI from circumflex artery occlusion. Door-to-ECG time

was 4 minutes and ECG-to-consult time was 18 minutes.

Cardiology noted there was no STEMI criteria and the first

troponin was in the normal range (25ng/L, with normal <26), so alternate

diagnoses were considered and the patient was sent for CT to rule out aortic dissection.

This is step 4: relying on the first troponin level to rule out acute coronary

occlusion. Even though the patient had prolonged chest pain, it was fluctuating

(which can be from spontaneous reperfusion/reocclusion) and only increased in

intensity 2 hours before presentation, so a normal troponin level is not

surprising. In a study last year, 14.4% of patients diagnosed with STEMI had an

initial troponin less than the 99th percentile, including 23.4% of

those who presented within two hours and 18.1% of those with posterior MI.[4]

CT revealed no dissection but extensive coronary

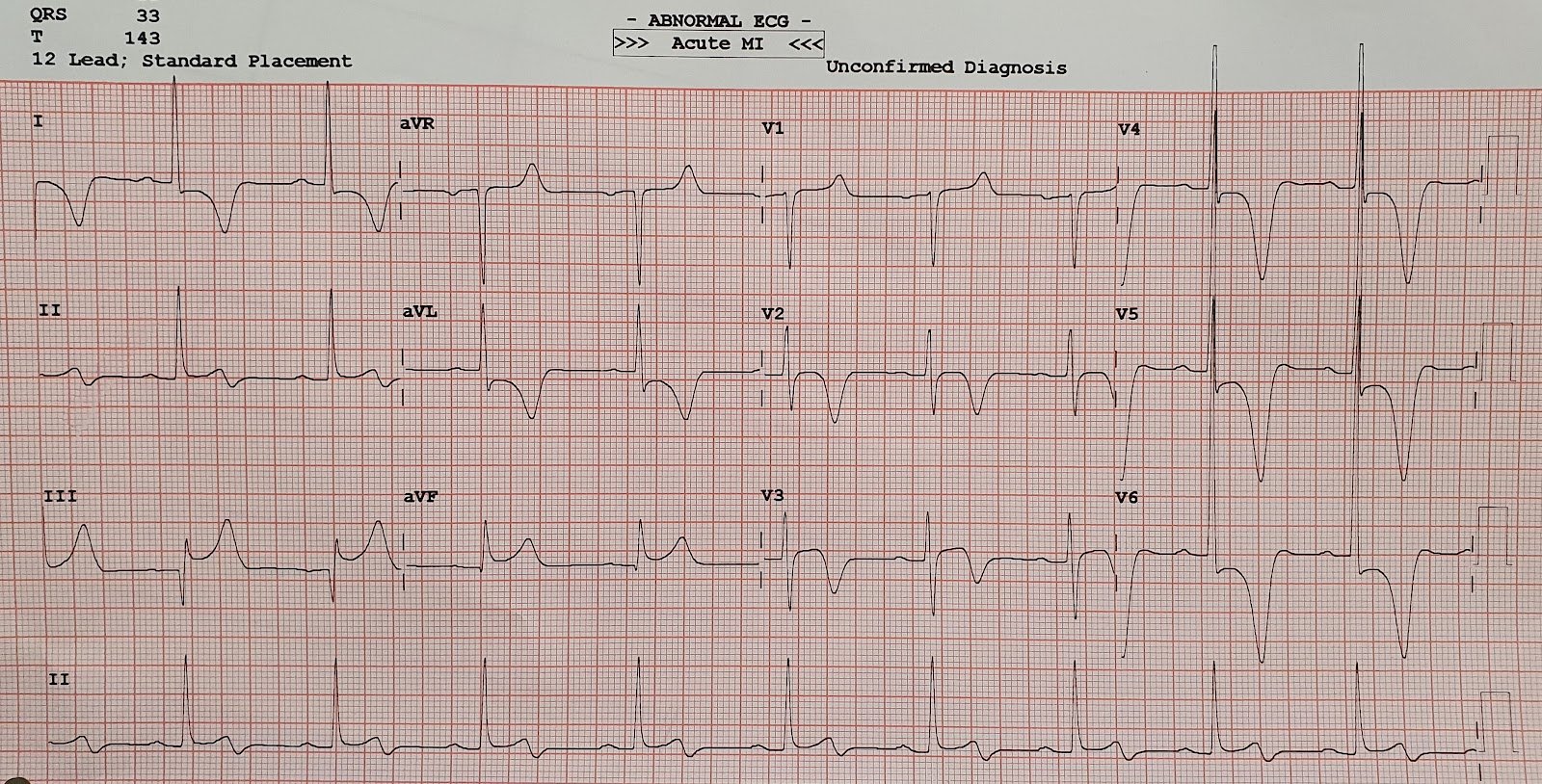

atherosclerosis. The patient was still in pain, repeat troponin was 50, and a repeat

ECG was done—labeled as normal by the machine:

This is step 5: relying on computer interpretation. Some

have suggested that ECGs labeled “normal” are unlikely to have clinical

significance, but this has been disputed.[5] Here there is recurrence of anterior

ST depression and now ST depression in aVL which is reciprocal to mild ST

elevation in III, which is diagnostic of inferoposterior OMI.

The patient was still in pain, with a third troponin of 500.

So even without the diagnostic ECGs, they had clinical evidence of refractory

ischemia with biomarker (troponin) confirmation. But they didn’t meet STEMI criteria so

they were put on an IV nitro drop, with escalating dose. This is step 6:

treating refractory pain and a rising troponin medically, without urgent

angiography as even STEMI guidelines recommend.[6]

After a fourth troponin rose to 4,000, the cath lab was

activated—16 hours after the first ECG—and found a 100% circumflex occlusion. Peak

troponin was 11,000 and echo revealed an inferobasal regional wall motion

abnormality corresponding to the ECG. Discharge ECG had new Q in III and

reperfusion T wave inversion in III/aVF and V6 (still labeled “normal” by the

computer):

Discharge summary: “ECG consistent with ischemia (STD V2-6)

and elevated troponin, managed as NSTEMI,” with a discharge diagnosis of

NSTEMI. This is step 7: retrospectively applying the NSTEMI label to patients

with a totally occluded artery. Because of this discharge diagnosis, the prolonged

reperfusion delay is not considered an opportunity for improvement, which

perpetuates reperfusion delays.

This is an example of “The No False Negative Paradox”: there is no possibility of a False Negative ECG in the STEMI paradigm. If the artery is occluded, but there was no diagnostic ST Elevation, it was not a STEMI even though an occlusion with irreversible myocardial damage was present.

This shows that “NSTEMI” is a worthless term. It encompasses the complete range of ACS, including OMI, NOMI, and coronary thromboses that have the potential to rapidly propagate and become OMI and therefore has no specificity. Non-OMI, or NOMI specifies that the artery is open and there is no ongoing irreversible process of infarction. However, one should also beware that NOMI can become OMI with propagation of thrombus.

Not only is the OMI designation more accurate in hindsight

based on the angiographic outcome, but prospective application of the OMI

paradigm in real time predicted the occlusion and specified the artery with

greater accuracy than the retrospective discharge summary (which claimed the

ECG had nonspecific ST depression from subendocardial ischemia). The

ECG-to-Activation time based on the OMI paradigm would have been 18 minutes and

the patient would have had reperfusion before a significant troponin rise, but

instead the ECG-to-Activation time was 16 hours after significant and

preventable infarction.

This is why we need the OMI paradigm shift: to correctly

classify MI by the actual pathology (occlusion vs non-occlusion), to learn the

resulting ECG changes, to apply them in clinical context (along with clinical

factors and echo findings), to track quality metrics for all OMI patients not

just those who meet STEMI criteria, and to promote quality improvement.[7]

Take home

1. —STEMI criteria miss Occlusion MI, especially posterior

2. —Posterior leads can be falsely negative

3. —Primary ST depression of ANY amount isolated to the anterior

leads is specific for posterior STEMI(-)OMI

4. —First troponin levels are not sensitive enough

5. —Don’t trust computer interpretations, including

‘normal’

6. —Refractory ischemia requires urgent angiography

regardless of ECG findings

7. —The STEMI/NSTEMI paradigm only tracks quality

metrics for STEMI(+)OMI patients, and perpetuates reperfusion delays for

STEMI(-)OMI patients. We need to shift to the OMI/NOMI paradigm, track

reperfusion delays for all OMI patients, and identify opportunities for

improvement.

–In the STEMI paradigm, there can be no false negative ECG. This is why “NSTEMI” is worthless term.

References

1. —Hillinger P, Strebel I, Abacherli R, et

al. Prospective validation of current quantitative electrocardiographic

criteria for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2019

2. —Meyers

HP, Bracey, Smith et al. Ischemic ST depression maximal in

V1-V4 (vs. V5-V6) of any amplitude, is specific for Occlusion Myocardial

Infarction (vs. non-occlusive ischemia) JAHA 2021

3. —Meyers HP, Bracey A, Lee D, et al. Comparison of

the ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) vs NSTEMI and Occlusion MI (OMI)

vs NOMI paradigms of acute MI. J of Emerg Med 2021.

–Meyers HP, Bracey A, Lee D, Lichtenheld A, Li W. Singer D, Kane J, Dodd KW, Meyers K,

Shroff GR, Singer A, Smith SW. Accuracy

of Expert Electrocardiography versus ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction

Criteria for Diagnosis of Acute Coronary Occlusion Myocardial Infarction.

International Journal of Cardiology Heart and Vasculature 2021.

4. —Wereski R, Chapman AR, Lee KK, et al. High

sensitivity cardiac troponin concentrations at presentation in patients with

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA Cardiol 2020

5. —Litell JM, Meyers HP, Smith SW. Emergency

physicians should be shown all triage ECGs, even those with a computer

interpretation of ‘normal’. J Electrocardiol 2019

6. —Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et

al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation

acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of

Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.

Circulation 2014

7. —McLaren JTT, Meyers HP, Smith SW, Chartier LB.

From STEMI to Occlusion MI: paradigm shift and ED quality improvement. CJEM

2021

===================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (1/3/2022):

===================================

Excellent case presentation by Dr. Jesse McLaren!

As I have suggested on many occasions in Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog (a few such links provided below) — the problem in recognizing acute Posterior OMI seems to be in the unfamiliarity of some providers that ST depression in the anterior leads is the “mirror-image” of what would otherwise be ST elevation in posterior leads.

- The concept is simple, and based on the fact that the standard 12-lead ECG does not directly view the posterior wall of the Left Ventricle. To resolve this — one could either apply posterior leads (in the form of leads V7, V8 and V9 — which continue on laterally and posteriorly along the chest wall after lead V6) — OR — one could simply look at a mirror-image opposite picture of the anterior leads on a standard 12-lead ECG. It is this latter approach that I have called, “the Mirror Test”.

- The problem with using posterior leads — is that the heart’s electrical activity is significantly dampened by distance and denseness of tissues in the path from these posteriorly-placed electrode leads V7, V8 and V9, on the way to the heart — such that ST segment amplitudes are significantly reduced. As a result, even if you do see ST elevation in these posterior leads — the amount of ST elevation is usually minimal and not easy to appreciate. It’s much EASIER to appreciate the acute ST segment changes of posterior infarction from the change in shape and amount of ST depression that you can readily see in the anterior leads with the Mirror Test.

- To do the “Mirror Test” — simply flip the ECG over … — Then hold the ECG up to the light to see the mirror-image view of the anterior leads. Computers now make this EASY — Simply select the lead (or leads) of interest — Choose “flip vertical” in your settings — and you instantly have a mirror-image view (Figure-1):

KEY Point: For posterior infarction — We focus on chest leads V1 through V4:

- As opposed to what happens with diffuse subendocardial ischemia — in which we see generalized, and usually a comparable amount of ST depression in at least 7 or 8 leads (with ST elevation in lead aVR) — with posterior infarction, the amount of ST depression is most in leads V1-thru-V4, and usually maximal in lead V2 and/or lead V3. Thus, the area of maximal ST depression is localized when there is posterior MI — and it is not localized when there is diffuse subendocardial ischemia.

- An additional clue that the ST depression you see in the anterior leads is the result of posterior MI — is often forthcoming by the finding of acute ST elevation in the inferior leads. This is because the most common cause of posterior MI is acute RCA occlusion — since the RCA typically supplies both the inferior and posterior left ventricular walls. (NOTE: This clue of inferior lead ST elevation won’t be seen if there is isolated posterior OMI).

- Final POINT: Let me emphasize the following: I am not saying that you should never do posterior leads. Clearly — posterior leads are standard procedure in many EMS systems, and they are routinely ordered by many emergency providers. Instead, what I am saying — is that it is possible to make the diagnosis of acute posterior infarction much more quickly and easily by simply using the standard 12-lead ECG. From my own experience — I don’t think I have ever seen a case in which posterior leads told me something that I did not immediately know by looking at the standard 12 lead ECG. With just a little bit of practice — it becomes EASY to mentally apply the Mirror Test in your head — and therefore diagnose acute posterior infarction without need to delay for placement of posterior leads, that are often unrevealing.

=================================

Selected LINKS on this Topic:

- ECG Blog #246 — Reviews the concept of the “Mirror Test” with a clinical example.

- The September 21, 2020 post in Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog — My Comment (at the bottom of the page) emphasizes utility of the Mirror Test for diagnosis of acute Posterior MI.

- The February 16, 2019 post in Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog — My Comment (at the bottom of the page) emphasizes utility of the Mirror Test for diagnosis of acute Posterior MI.