This was written by Emerson Floyd, with comments by Smith

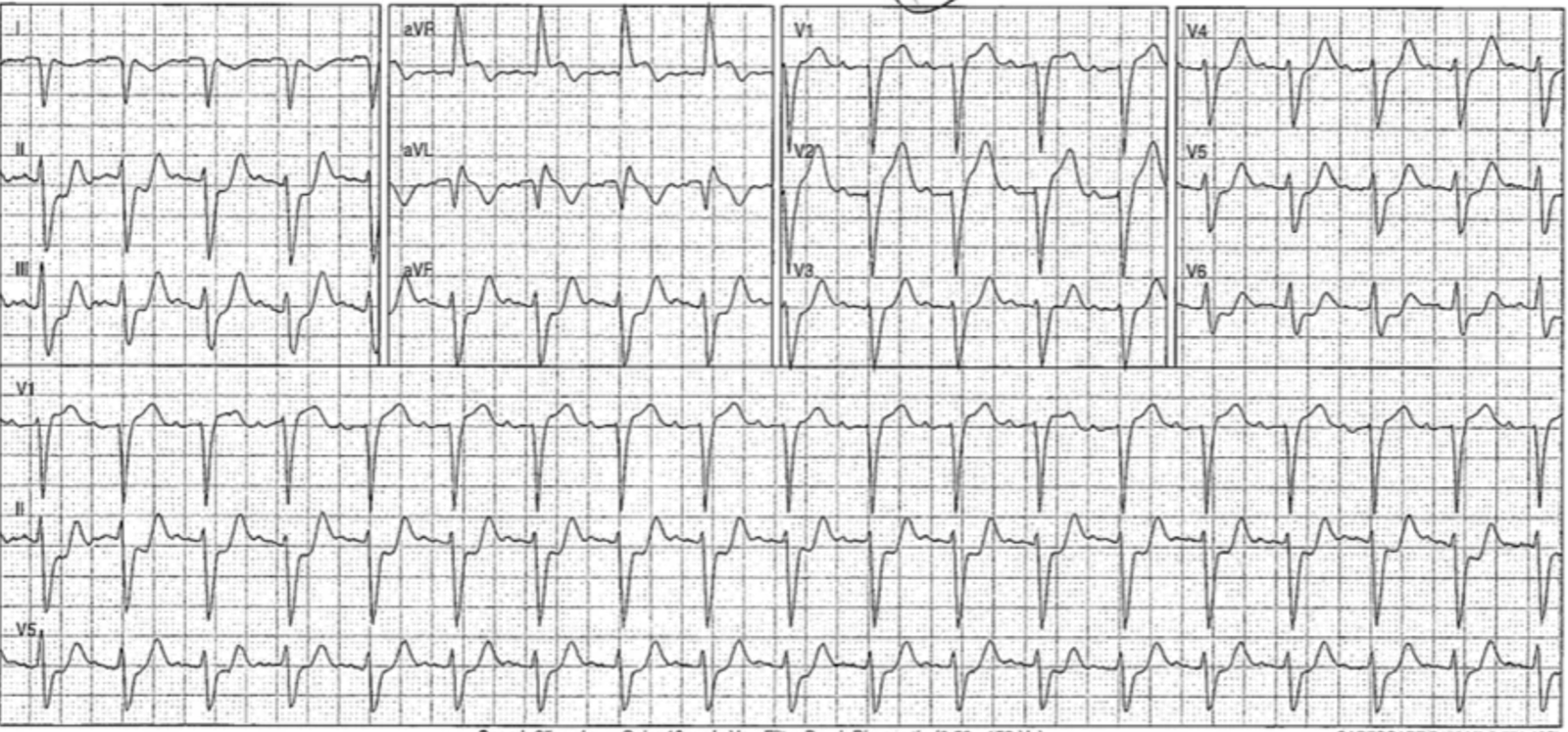

I first saw this this ECG (#1) when I woke up to a text message a fellow EM physician and friend between night shifts:

“I accepted this patient in transfer from a remote hospital without a cath lab. Our IC said to hold on lytics based on the ECG. Transferring doc was worried about left main occlusion based on aVR. Sgarbossa+? I never saw the patient.”

Smith: see @PMCardio Queen of Hearts interpretation below.

The first things that caught my half-asleep eye were the extreme axis, the totally upright complex in aVR and the depressions in the inferior and lateral leads. “Looks bad, something’s off,” I thought sleepily and went back to bed. When I woke up I looked again and recognized that the above constellation of findings represented OMI with arm lead reversal: lead aVR and aVL had switched places, lead I was inverted. When interpreted in this context the ECG was diagnostic of proximal LAD or first diagonal occlusion.

I asked my friend for all the deidentified information about the case they could provide.

80-year-old patient with HTN and HLD presented at 150 pm for midsternal chest pain since noon.

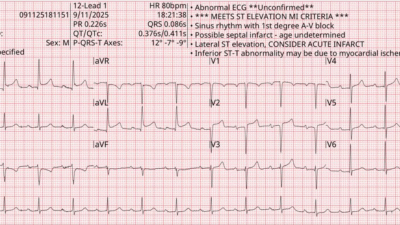

The following ECG was obtained by EMS on scene, confirming my initial impression:

This is diagnostic of proximal LAD or first diagonal occlusion. In the limb leads, the most obvious changes are the inferior reciprocal depressions and the elevation in aVL. There is also elevation in V1 an V2 with depressions in V5 and V6 consistent with the “precordial swirl” pattern discussed by Smith, Meyers, etc. Of note, obvious changes in lead I, a component of the commonly taught “South African Flag” mnemonic to recognize this injury pattern, are absent.

Smith: lead I has a depressed ST takeoff and a straight ST segment, so it is doing its part in the SAF morphology, but without ST elevation.

Unfortunately, the physician at this remote facility did not recognize the lead reversal on ECG #1. His interpretation of this ECG: “Was evaluated on arrival nontoxic and hemodynamically stable she is mildly tachycardic at 113. EKG shows ST elevation in aVR with diffuse ST depression concerning for left main occlusive MI, lbbb with discordance.”

_______

Smith comment: STE in aVR with diffuse ST depression is very often, but erroneously, attributed to left main occlusion. It indicates widespread subendocardial ischemia and can be a manifestation of left main insuffieciency, which MAY be an indication for the cath lab, but it is not a manifestation of total occlusion.

See this post on left main occlusion: How does Acute Total Left Main Coronary occlusion present on the ECG?.

And this one on STE in aVR: Does ST Elevation in lead aVR indicate acute coronary occlusion?

________

The interpreting physician was right to notice how concerning the depressions were! But the depressions in all the inferolateral leads were suggestive of a specifically injured territory, not just the general subendocardial ischemia suggested by elevation in aVR with depression in II, V5 and V6. They were also incorrect to diagnose left bundle branch block. As noted by K. Wang and others, LBBB requires monophasic R waves in I, avL and V6.

Smith: OMI can be diagnosed on the first ECG even if you don’t recognize the lead reversal. Also, whether it is LBBB or Non-specific intraventricular conduction delay, the concordant ST Elevation (see aVR and aVL) still is diagnostic. And so none of this matters to the Queen of Hearts.

New PMcardio for Individuals App 3.0 now includes the latest Queen of Hearts model and AI explainability (blue heatmaps)! Download now for iOS or Android. https://www.powerfulmedical.com/pmcardio-individuals/ (Drs. Smith and Meyers trained the AI Model and are shareholders in Powerful Medical).

The patient got aspirin en route. The physician obtained consent for TNK based on the patient’s appearance and their concern for left main occlusion based on seemingly widespread depressions and STE in aVR. But, after reviewing the ECG, the Interventional Cardiologist at the outside hospital asked the ED physician not to give lytics, instead recommending heparin and transfer. On a second discussion, the interventional cardiologist asked for a CT angiogram to assess for dissection prior to transfer.

Smith comment: only approximately 1% of “STEMI” (a subset of OMI which meet STEMI mm critieria) are due to dissection. To take the time to get a CT is detrimental to patient care. Use bedside ultrasound to look for dissection, and learn how to do so. I This study showed very high sensitivity and specificity of bedside ultrasound for Aortic dissection. See this case here from 3 days ago: A very elderly woman with sudden severe chest pain radiating to her back.

As the patient had continuing chest pain, an additional ECG was obtained an hour and a half after the first:

The same lead reversal pattern was present on this ECG. This was read as “EKG shows ST elevation in aVR with diffuse ST depression concerning for left main occlusive MI, LBBB with discordance.”

What strikes me on this repeat ECG is how the LAD territory injury in the precordial leads has even more obvious “swirl”, with deepened reciprocal depressions in V5 and V6 compared to prior. In an 80 year old female, both this and the initial “misleading” ECG met STEMI criteria: about 1.7 mm in V1 and 2 mm in V2. If the Emergency Physician hadn’t anchored on aVR elevation as the most telling marker of injury they may have made a persuasive argument despite failing to recognize lead misplacement.

Smith: V1 and V2 also have hyperacute T-waves, confirming the diagnosis of precordial swirl. Precordial swirl is due to occlusion proximal to the septal perforator. South Africa flag sign is due to occlusion of D1 or LAD proximal to D1. So this is going to be an occlusion of the LAD proximal to BOTH.

The patient’s transfer was held while awaiting the final read on the CT angiogram. Her high sensitivity troponin returned at 1981 ng/L (normal <50) at 1400. At 1600, the angiogram was read as without dissection and the patient was transferred to the outside hospital.

Upon arrival at the outside hospital the patient was pain free. In keeping with this history, the biphasic, terminally inverted t-wave in lead aVL on arrival around 2000 suggests some degree of reperfusion:

Smith: and T-waves are no longer hyperacute. There is an inverted reperfusion T-wave in aVL and reciprocally upright T-waves in inferior leads.

Her troponin at 2111 resulted at 53.8 ng/mL (normal < 0.34 ng/mL), nearly triple the initial value if roughly comparing these different troponin assays.

Smith: 53.8 ng/mL is a VERY large infarction.

The interventional cardiologist was spoken to upon the patient’s arrival. He opted to wait until the next day to catheterize the patient, who remained chest pain free until this procedure at about 1000:

with the following interventions performed:

Indeed, the lesion is proximal to BOTH the septal perforator and D1.

Her ECG post-cath demonstrated further LAD reperfusion, with a symmetrically inverted t-wave in aVL and a biphasic, terminally inverted t-waves in V2:

The post-cath echocardiogram demonstrated an ejection fraction of 40% with a hypokinetic to akinetic anteroseptum and a hypokinetic mid to anterior apical wall and inferoapex.

Five Lessons from this Case:

This is an unfortunate case where the patient likely lost an unnecessary amount of myocardial function secondary to ECG interpretation mistakes by both an Emergency Physician and an Interventional Cardiologist. But it contains many lessons that others can learn from. I have picked out five.

Smith: Fortunately for the patient, there was spontaneous reperfusion, aided by aspirin and heparin. But this reperfusion was only AFTER a large amount of permanent, irreversible myocardial loss.

Lesson 1: always review ECGs in context of priors. Lead misplacement may have been correctly diagnosed if the EMS strip on arrival was compared to the initial ECG obtained in the ED. For all I know it actually was. Which leads to:

Lesson 2: learn to identify limb lead misplacement. I cover a method for catching lead misplacement in the first lecture I give to my residents and other learners every year. I teach it right after I teach the elements of a normal sinus rhythm: it is that critical and fundamental a skill. Just in terms of diagnosing OMI, both false negatives and false positives can be generated by lead misplacement. For instance, Dr. Jesse McLaren shares a case on Emergency Medicine Cases where a patient underwent unnecessary catheterization based on the following left arm/right leg lead reversal ECG:

The ECG with corrected placement looks like this:

Many ECG interpretation experts I know can instantly recognize and categorize limb lead misplacement. However, I do not have that expectation of most experienced Emergency Attending Physicians, let alone a fourth-year medical student or EM intern that I’m teaching. Accordingly, I teach the following “cues” to identify some form of limb lead misplacement and prompt a carefully recorded repeat ECG:

- 1. Upright p and qrs in aVR

- 2. Inverted p’s in other leads

- 3. “Flat line” tracing in a lead

- 4. Extreme axis

While difficult to appreciate, the initial ECG in this case demonstrates “1. Upright p and qrs in aVR”, “2. inverted p’s in (I and avL)” and “4. Extreme Axis.”

Lesson 3. Lead I in the high lateral “South African Flag” injury pattern is not always obviously changed.

Let’s assume that the prehospital ECG was repeated in the ED and looks similar. Just the precordial leads alone would prompt a typical reader of this blog to have a high suspicion for “precordial swirl.” But on this whole this ECG suggests the “South African Flag” pattern as it is often taught to medical students and EM trainees: ST elevation in I and avl, ST depression in lead III and ST elevation in V2.

(Above figure courtesy of Ken Grauer via https://drsmithsecgblog.com/a-woman-in-her-30s-with-sudden-chest/)

I have seen multiple cases where the changes in lead I are not as obvious as the changes in the other named “South African Flag” leads. And this can lead to a delayed or missed proximal LAD or D1 occlusion diagnosis because there aren’t clear “contiguous” leads to support a territorial injury. The lesson: It is important to understand aVL and the septal leads as “contiguous leads” corresponding to a proximal LAD or first diagonal territory. In terms of the “South African Flag” mnemonic, the top left portion of the flag can often be subtle.

Lesson 4: Learn the necessary elements of a Left Bundle Branch Block

The intial ECGs in this case are indeed wide complex, with QRS durations in some leads over 120 ms. But it is not a left bundle branch block. As noted above, a left bundle branch block ECG must have monophasic R waves in leads I, aVL and V6.

Lesson 5: Understand aVR and the “demand pattern.”

I teach aVR to my trainees as “the great reciprocal.” This is the one lead that does not “overlie” ventricular myocardium. Accordingly, elevation or depression in this lead does provide information about ischemia in one specific myocardial territory. Rather, elevation in this lead is reciprocal to widespread depression with an ST depression vector towards II and V5, particularly in what I call as the “demand distribution”: in subendocardial ischemia without a clear territorial culprit, maximum ST depression will often be observed in leads II, V5 and V6. Some cases on this blog and elsewhere demonstrate this pattern in association with a left main or proximal LAD plaque rupture in patients with very robust collateral circulation. But the picture this ECG paints is not one of a particular territory abruptly deprived of oxygenation. Rather – absent any other localizing features – it is one of global demand ischemia that can be seen in any kind of shock, from sepsis to GI bleed. If not a baseline finding (which can be the case with LVH), I teach residents that this pattern should trigger a consideration of someone who is 1) in shock and very sick and 2) in need of careful thought about what is causing them to be in shock.

However, since elevation in this lead is not diagnostic of transmural ischemia, it would not in my opinion be sufficient to satisfy the Sgarbossa criteria based on concordant elevation in one lead.

Smith: when leads are correctly placed, aVR is virtually always predominantly negative, including in LBBB. So, in LBBB, ST elevation cannot be concordant. But it CAN be proportionally excessively discordant, and when it is, it is reciprocal to widespread ST depression, just as in normal conduction. And if it is very discordant (>30%), one could diagnose OMI if it is the correct clinical scenario (not demand ischemia)

Final thoughts:

A challenge of Emergency Medicine is that the care patients receive by specialists is often only as good as the case the Emergency Physician makes. In retrospect, the emergency physician who had the benefit of a bedside encounter with the patient seemed to be convinced that she was having a heart attack. He tried to render good care, consenting the patient for lytics and calling the interventional cardiologist twice about potentially giving them. But by anchoring on an incorrect interpretation of the ECG – Left Bundle Branch Block, Sgarbossa + based on aVR rather than high lateral injury with arm lead misplacement with STEMI+ septal injury with lateral precordial reciprocals – he failed to make a sufficient case for lytics to an interventional cardiologist.

======================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (9/13/2025):

In today’s post — Dr. Floyd expands on a series of oversights, beginning with the initial ECG that was texted to him. Assessment of this initial tracing was complicated by LA-RA Lead Reversal, that significantly altered the appearance of limb leads in this tracing.

- I focus My Comment on this initial ECG — first by quick review on what alterations in ECG appearance to expect with LA-RA Lead Reversal (See Figure-1) — and then with illustration in Figure-2 as to what today’s initial tracing would have looked like had the leads been properly placed.

My favorite on-line “Quick GO-TO” reference for the most common types of lead misplacement comes from LITFL ( = Life-In-The-Fast-Lane). I have used the superb web page they post in their web site on this subject for years. It’s EASY to find — Simply put in, “LITFL Lead Reversal” in the Search bar — and the link comes up instantly.

- This LITFL web page describes the 7 most common lead reversals. There are other possibilities (ie, in which there may be misplacement of multiple leads) — but these are less common and more difficult to predict.

- By far (!) — the most common lead reversal is mix-up of the LA (Left Arm) and RA (Right Arm) electrodes. This is the mix-up that occurred in ECG #1a. For clarity in Figure-1 — I’ve reproduced the illustration from LITFL on LA-RA reversal.

- KEY Point: LA-RA Lead Reversal is EASY to recognize when you see “global negativity” in lead I (ie, When the P wave, QRS complex and T wave are all negative in lead I ). Even when P waves are absent (or P waves in lead V1 are tiny — as in today’s case) — a completely negative QRS complex in lead I is almost never seen in a supraventricular rhythm!

- NOTE: I’ve collected and organized over 20 examples of lead reversals (as well as many additional examples of various “technical misadventures) that are important to recognize. This guide can be easily accessed from the Menu Tab at the top of every page in Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog — Simply CLICK HERE —

= = =

Figure-1: LA-RA Lead Reversal (adapted from LITFL).

= = =

Applying Figure-1 to Today’s CASE:

For clarity — I’ve taken the initial ECG in today’s case ( = ECG #1a) — and inverted lead I — switched leads II and III — and switched leads aVL and aVR ( = ECG #1b, which is the lower tracing in Figure-2).

- Note that the “telltale findings” of LA-RA Lead Reversal ( = global negativity of P wave, QRS and T wave in lead I — and the all upright QRS in lead aVR) are no longer present in ECG #1b.

Now that the appearance of the QRST complex in today’s initial ECG is as it would have been had the LA and RA electrodes been properly placed — we can more easily interpret from ECG #1b the principal findings of this initial tracing:

- There is sinus tachycardia.

- The QRS complex is widened — but as per Dr. Floyd, rather than LBBB, the persistent deep S waves in the lateral chest leads is most consistent with IVCD (IntraVentricular Conduction Defect) with a marked left axis (predominant QRS negativity in all 3 inferior leads).

- The abnormal ST elevation in lead V1 — and disproportionately enlarged ST-T wave in neighboring lead V2 — together with shelf-like ST depression in lead V6 (and to a lesser extent in leads V4,V5) in this 80-year old patient with new CP (Chest Pain) are strongly suggestive of Precordial “Swirl“ from a proximal LAD occlusion.

- This impression is supported in ECG #1b by the limb lead findings of: i) ST elevation in lead aVL and lead I; — and, ii) Reciprocal ST depression in each of the inferior leads.

- Of note is terminal T wave inversion in lead aVL, with terminal T wave positivity in the inferior leads — that may represent a component of spontaneous reperfusion.

- To Emphasize: The ST elevation in lead aVL that so often accompanies (and supports our diagnostic impression of) proximal LAD occlusion — was not identifiable on today’s initial ECG because of the LA-RA Lead Reversal.

= = =

Figure-2: I’ve reproduced today’s initial ECG — and in the bottom tracing, have corrected for what this initial ECG would look like if the leads were correctly placed. (To improve visualization — I’ve digitized these tracings using PMcardio).