Written by Jesse McLaren

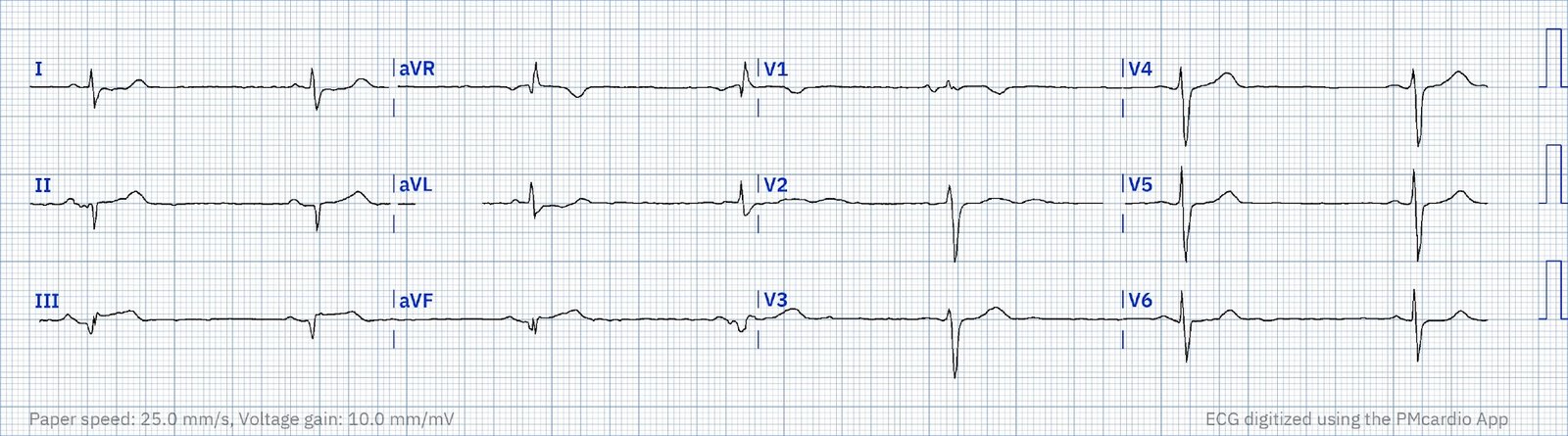

A 75 year old

with a history of CABG called EMS after 24 hours of chest pain. HR 40, BP

135/70, RR16, O2 100%. Here’s the paramedic ECG (digitized by PMcardio). What

do you think?

There’s sinus

bradycardia, normal conduction, normal axis, delayed R wave progression, and

normal voltages. There are inferior Q waves and lead III has mild concave ST

elevation, with subtle reciprocal ST depression in I/aVL. This is diagnostic of

inferior OMI, likely from the RCA. The patient has a history of CABG so some of

these changes could be old, but with ongoing chest pain and bradycardia in a

high risk patient this is still acute OMI until proven otherwise.

I sent the ECG

to Dr. Meyers without any information, and he immediately replied, “inferior

OMI.” I also sent this to the PMcardio app Queen of Hearts. Trained by Smith

and Meyers, it delivered the same immediate reply of OMI with high confidence:

But there are

multiple barriers to getting the patient to the cath lab:

a. STEMI negative: the EMS automated

interpretation read, “STEMI negative. Inferior infarct, age undetermined. Sinus

bradycardia.” According to the STEMI paradigm, the patient doesn’t have an

acute coronary occlusion and doesn’t need emergent reperfusion, so the

paramedics can bring them to the ED for assessment, without involving

cardiologists. But the latest ACC consensus on the evaluation of chest pain in

the ED warns that “STEMI criteria will miss a significant minority of patients

with acute coronary occlusion.”[1]

b. late presentation: even if there were

STEMI criteria, the patient presented with 24 hours of chest pain, and with Q

waves – both of which are often (wrongly) considered outside the window for

treatment. In a study evaluating the reasons why STEMI patients do not receive

reperfusion, patient delay greater than 12 hours from symptom onset was the

most common reason.[2] This despite evidence of myocardial salvage in late

presenters (12-72h) with total occlusion.[3]

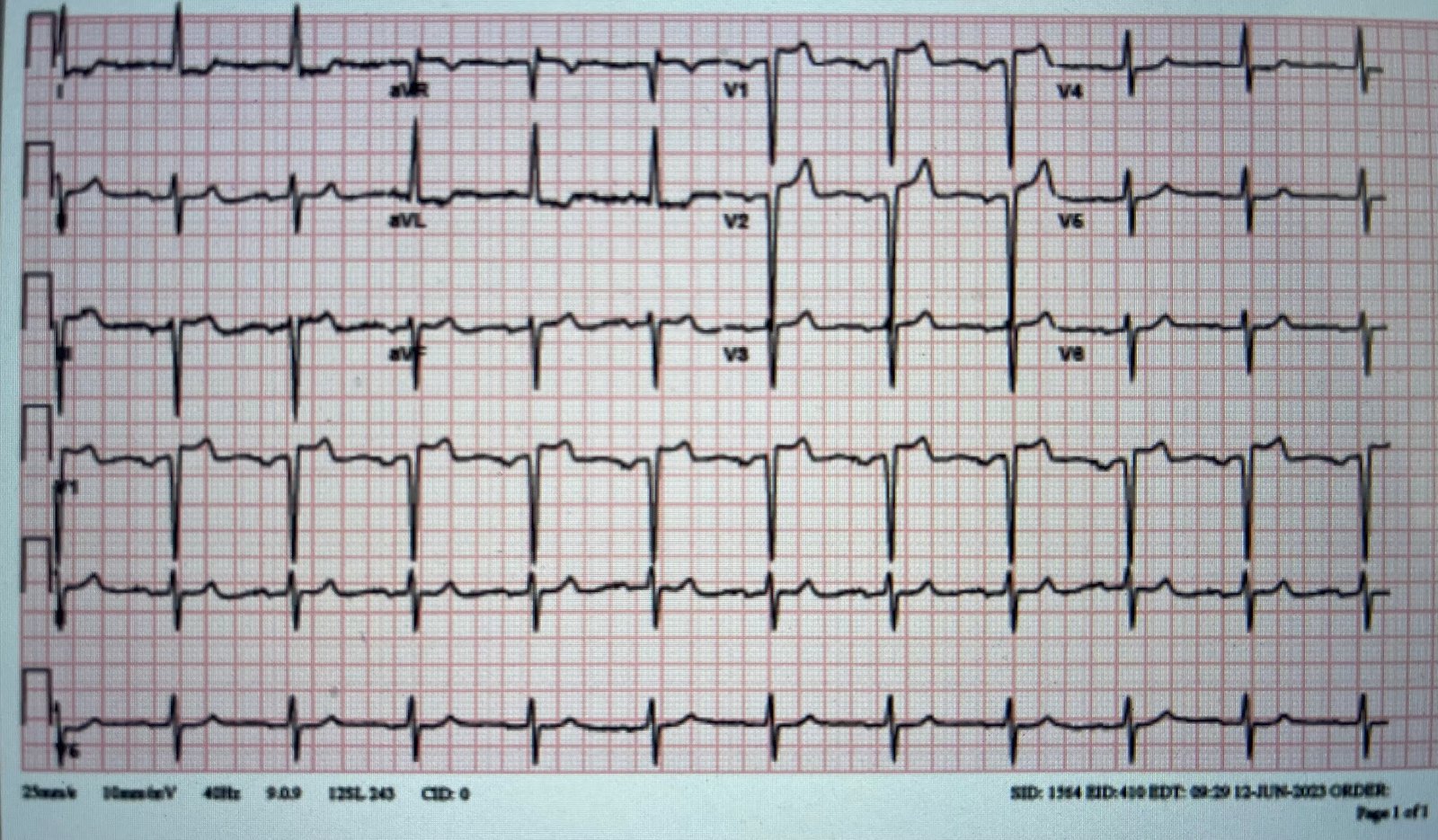

b. transient ST elevation but ongoing

occlusion. Even if the patient had presented acutely with STEMI criteria,

the ST elevation resolved on arrival though the pain continued. Here’s the

first and repeat paramedic ECG:

According to some

interpretations of the literature on “transient STEMI”, this patient doesn’t

need the cath lab because ST segments improved. For example, the TRANSIENT trial randomized patients with transient STEMI to immediate vs delayed invasive strategy and concluded that “infarct size in transient STEMI is small and is not influenced by an

immediate or delayed invasive strategy. In addition, short-term MACE was

low and not different between the treatment groups.”[4] But the inclusion criteria was that patients “must have complete relief of symptoms and complete normalization of ST-segments.” And even then there was a risk of reocclusion with cath lab delay.

As an analysis of the TRANSIENT trial explained, “there are concerning signals in this

under-powered trial. There were trends toward larger infarct size with

delayed angiography, both by cMR and integral high-sensitivity troponin

concentration, as well as toward higher rate of major adverse

cardiovascular events (MACE) (8.5 vs. 2.9%; P = 0.28) in the

delayed group. This latter figure includes the four patients randomized

to delayed angiography who underwent urgent revascularization for

recurrent ischaemia, and mirrors a trend observed in the ELISA-3 post hoc

analysis of transient STEMI patients. As recurrent ischaemia is the

principle event reduced by early intervention in NSTE-ACS, these are

important endpoint events occurring with delayed angiography and there

is a consistent signal for harm now from two data sources.”[5]

This patient had ongoing chest pain, bradycardia, and no signs of reperfusion T

wave inversion. Repeat ECG in the ED showed a hint of inferior ST elevation:

STEMI vs OMI paradigms

Following the

STEMI paradigm, the most likely evolution of this case would be:

1.

paramedic

transportation to the ED as “chest pain, STEMI negative”

2.

ED

consult for “non-STEMI” when the trop comes back elevated

3.

Cardiology

admit as “non-STEMI” for non-urgent angiogram

4.

Discharged

diagnosis of “Non-STEMI”, regardless of angiographic findings, peak troponin or

echo

But instead,

this patient received excellent care by disregarding the STEMI paradigm and

focusing on the reperfusion of acute coronary occlusion:

1.

Despite

no STEMI criteria, the paramedics advocated for a stat cardiology consult out of

concerns for an acute coronary occlusion—because of high pretest probability

and subtle ECG signs of occlusion. As they documented, “Paramedics noted

patient’s 12 Lead appeared to have 1mm of elevation in III and borderline 1mm

elevation in aVF, with mild depression in I and aVL. Due to these borderline

findings and patient’s cardiac history, cardiac interventionalist was called

for consult.”

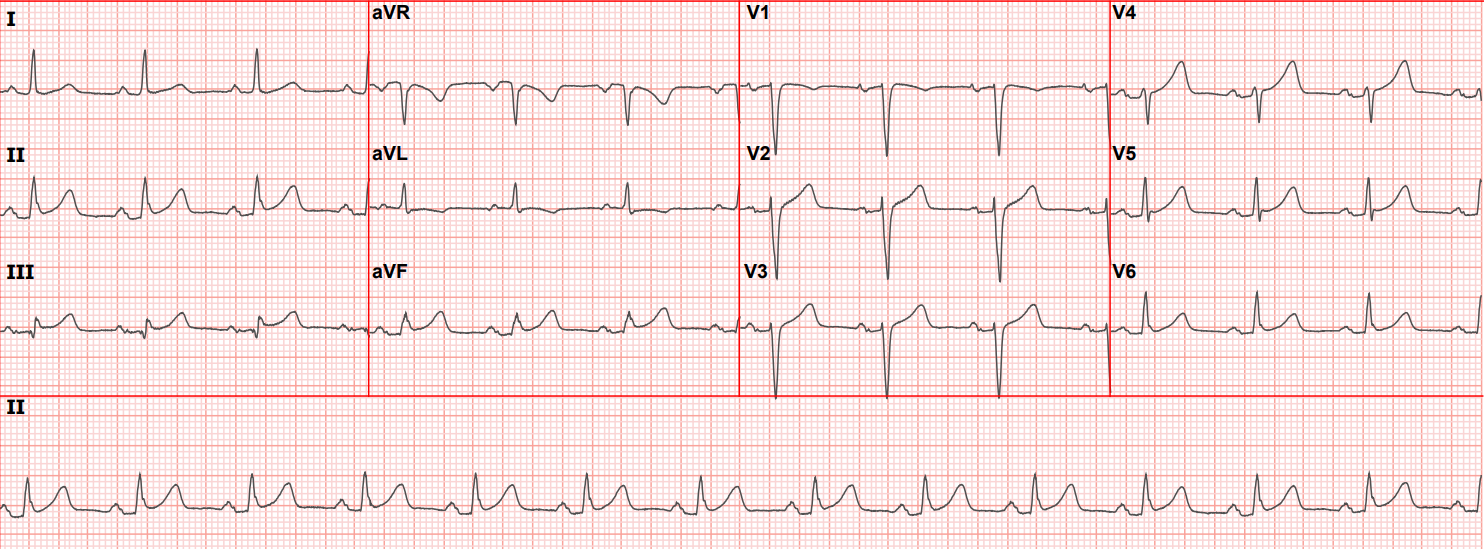

2.

Cardiology

documented “late presentation STEMI but likely aborted given resolution

of ST changes from EMS to hospital.” But they still took the patient

immediately to the cath lab, with a door-to-cath time of 45 minutes.

The patient had a 100% occlusion of the RCA graft. Initial

troponin I was 4,000 ng/L (normal <26 in males and <16 in females) and

rose to 14,000 (confirming it was not a ‘missed STEMI’ with peak troponin on

presentation, despite the 24 hours of pain). Follow up ECGs showed inferior

reperfusion T wave inversion:

The only problem

is that the discharge diagnosis was “STEMI” even though no ECG ever met STEMI

criteria. So this rapidly treated STEMI(-)OMI will be included in the STEMI

database showing the benefits of rapid reperfusion for “STEMI”, rather than being

recognized as one of many “non-STEMI” with occlusion that are at risk for delayed

reperfusion but that would do better with rapid reperfusion.

Take home

1.

STEMI

criteria, and automated interpretations based on it, will miss acute coronary

occlusion. But emergency providers including paramedics can learn signs of OMI,

which can be accelerated by expert-trained AI

2.

Prolonged

symptoms doesn’t mean completed infarct, and is not a reason to withhold

reperfusion

3.

Transient

ST elevation with ongoing symptoms still needs the cath lab

4.

The

OMI paradigm shift can begin locally, but databases should accurately classify

patients as OMI/NOMI rather than STEMI/Non-STEMI – both to identify preventable

delays to reperfusion, and to highlight successes like this case

References

1.

Kontos

et al. 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Evaluation

and Disposition of Acute Chest Pain in the Emergency Department: A Report of

the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll

Cardiol 2022 Nov 15;80(20):1925-1960

2.

Welsh

et al. Evaluating clinical reasons and rationale for not delivering reperfusion

therapy in ST elevation myocardial infarction patients: insights from a

comprehensive cohort. Int J Cardiol 2016

3.

Busk

et al. Infarct size and myocardial salvage after primary angioplasty in

patients presenting with symptoms for <12h vs 12-72h. Eur Heart J 2009

4 Lemkes et al. Timing of revascularization in patients with transient ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a randomized clinical trial. Eur Heart J 2019

5.

Bergmark BA, Faxxon DP. Transient

ST-segment myocardial infarction: a new category of high risk acute coronary

syndrome? Eur Heart J 2019;40:292-294