Written by Mazen El-Baba, with edits from Jesse McLaren

A 60-year-old woman presented to a rural emergency department with sudden-onset, crushing chest pain that began 20 minutes prior to arrival. She described it as a 10/10 heaviness in the center of her chest, without radiation or shortness of breath. Past medical history: hypertension on perindopril. She took two aspirin tablets at home before coming to the ED.

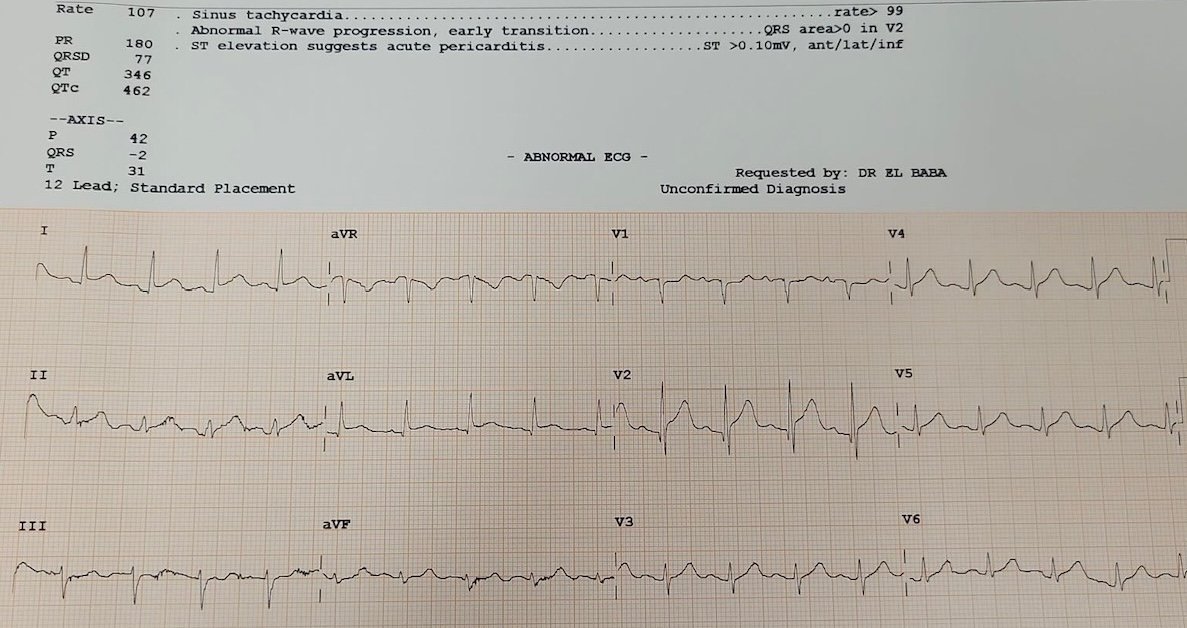

She was triaged to the resuscitation bay, and the first ECG was obtained, which the computer interpreted as pericarditis. What do you think?

ECG interpretation: Sinus tachycardia, borderline left axis, early R-wave progression in V2, normal voltages, subtle ST-elevation in leads I/aVL with reciprocal ST-depression in lead III, and ST-elevation with hyperacute T-wave in V2 with a small Q wave.

I was immediately concerned. The STE in V2 and I/aVL with reciprocal depression in III forms the “South African flag” pattern, often representing an occlusion of a diagonal branch of the LAD branch, and not pericarditis. The depressions in lead III automatically exclude the diagnosis of “pericarditis”. Moreover, pericarditis rarely shows localized reciprocal change or hyperacute T-waves. The focality of changes and the ischemic-type pain pointed toward OMI.

Smith: yes, this is diagnostic not only of D1 occlusion (South Africa Flag sign) but of proximal LAD OMI, as there are hyperacute T-waves all the way out to V6, and even lead II.

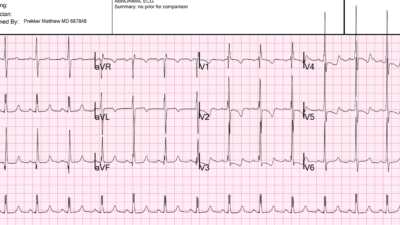

The Queen of Hearts agrees, (though she did not agree on one submission and she does so with low confidence– see discussion below). In this submission, she does not recognize the HATW from V3-6:

Here we apply our hyperacute T-wave quantitative analysis:

Red is HATW, and there must be 2 consecutive T-waves that average 0.7 score (a combination of “magnitude” score, which reflects AUC/QRS amplitude ratio, and symmetry score. You can see that there are two consecutive leads (V4-5) with scores of 0.7 and 0.8. Thus, our system does indicate hyperacute T-waves, with specificity of 98%.

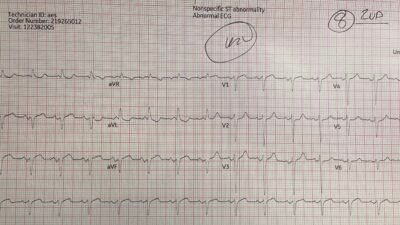

There was slight baseline wander in the limb leads of the 1st ECG that could affect the above noted subtle changes — so the 1st ECG was immediately repeated and compared to baseline ECG. Shown here is an ECG from a few years prior (Top tracing) — then the repeat ECG on the day of chest pain (Bottom tracing). Availability of this prior ECG confirms that the early R wave transition is old, and that not only is the South African flag pattern new — but hyperacute T waves are now seen across the precordium. So it now looks like proximal LAD occlusion (though the computer continued to label it as ‘pericarditis’):

Adjusting pre-test probability

Emergency medicine and cardiology decisions should not be binary (“STEMI vs not STEMI”). They are Bayesian: we start with a pre-test probability based on history and risk factors, and continuously update it as we gather more information.

Bayesian analysis of ACS and ECG are outlined in this pubication by Jose de Alencar and Smith (free full text): Bayesian Diagnosis of Occlusion Myocardial Infarction: A Case-Based Clinical Analysis

In this case:

- History: sudden, ongoing, pressure-like pain → high pre-test probability

- ECG: subtle reciprocal changes and hyperacute T’s → increased probability.

To gather more information to inform the pretest probability, I performed a bedside echo.

- Bedside echo: focal anterior wall hypokinesis → markedly increased probability.

Each step refined the probability upward, shifting management from “rule-out” to “treat until proven otherwise.”

This is especially important in a rural setting where the treatment for OMI is thrombolysis. The ECG machine labeled pericarditis and the history of sudden 10/10 chest pain raises the possibility of aortic dissection, both of which are contraindications for thrombolysis. But the ECG and POCUS findings excluded pericarditis, and OMI is highly unlikely to be secondary to aortic dissection.

Clinical reasoning and management

Given the remote setting, transfer to a PCI-capable center would require time. A bedside POCUS was performed to narrow diagnostic uncertainty, and it confirmed anterior wall hypokinesis consistent with LAD territory ischemia.

I contacted the regional interventional cardiologist and shared the ECG. At first, the recommendation was to heparinize and await air transfer, but after reviewing the ECG and the beside echo video, the interventionalist agreed the findings were highly suspicious for LAD occlusion and agreed to thrombolyse.

Given the expected delay to PCI, Tenecteplase (TNK) was administered. The patient was pre-treated with clopidogrel and LMWH as per anticoagulated protocol. Shortly before initiating reperfusion by administering TNK, the initial high-sensitivity troponin returned at 600 ng/L, further reinforcing that this was an acute infarction, not pericarditis.

Outcome

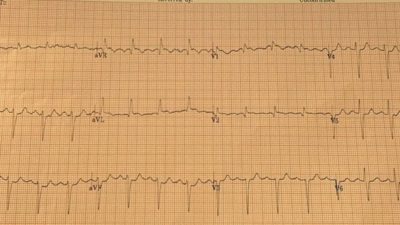

Thirty minutes after TNK, the patient’s chest pain completely resolved. Repeat ECG showed improvement of changes:

She was then flown to the cath lab and the accepting interventional cardiologist texted saying that the ECG has completely normalized upon arrival to their facility. The next day, coronary angiography revealed a very tight proximal LAD lesion with TIMI III flow, which was stented. She recovered well and was discharged several days later.

Discussion

This case illustrates several key principles central to the OMI framework and ECG-based decision-making.

STEMI criteria are insensitive

Traditional STEMI thresholds were never designed to detect all acute occlusions. Many OMIs produce subtle or regional ST-changes that fall below these thresholds. The goal is not to wait for a “STEMI” to appear (which may never happen), but to recognize when the clinical and ECG context together make occlusion overwhelmingly likely.

Pericarditis: diagnosis of exclusion

Pericarditis typically produces diffuse, concave, multi-territorial STE with PR-segment depression and no reciprocal STD (except aVR). It is also a clinical diagnosis that requires 2/4 following criteria: ECG criteria, a suggestive history, pericardial effusion on echo, and friction run on auscultation. OMI, in contrast, is focal, territory-specific, and often asymmetric, as in this case, where STE in I/aVL/V2 was balanced by STD in III. When reciprocal changes exist, particularly in the inferior leads, pericarditis becomes very unlikely. In addition, most pericarditis is idiopathic and improves with NSAIDS, so it should be a diagnosis of exclusion.

Pre-test probability is dynamic, not static

Diagnostic confidence should evolve with each new piece of evidence. Early on, the differential may have included aortic dissection, SCAD, pericarditis, or OMI. But a consistent story, subtle reciprocal changes, and wall-motion abnormality collectively raise the OMI probability high enough that waiting becomes riskier than treating. This Bayesian updating process is the backbone of emergency decision-making. When uncertainty exists, gather more data; not to delay, but to clarify your threshold to act: Serial ECGs, repeat exams, echo, +/- early troponins are all tools to dynamically adjust pre-test probability in real time.

POCUS as a probability-adjuster

A focal regional wall-motion abnormality increases the likelihood ratio for OMI dramatically. Echo doesn’t replace ECG; it complements it. In rural settings, bedside echo can make the difference between indecision and decisive reperfusion.

Troponin as confirmation, not a trigger

Troponin kinetics lag behind ECG changes. However, in this case, a markedly elevated initial value (600 ng/L) added further weight to the OMI diagnosis. It was obtained while the patient was receiving the TNK; do not wait for the initial troponin if your pretest probability is high enough because it may be falsely negative. The decision to thrombolyze was made on clinical + ECG + echo; the troponin simply reinforced what was already evident, but should not have changed management even if it had been normal.

Thrombolysis remains life-saving in the right setting

Thrombolysis is not without real risks. When the diagnosis is secure and PCI delay is expected, thrombolysis should not be viewed as a last resort but as an evidence-based intervention that restores flow and saves myocardium. Thrombolysis decision-making must still follow standard protocol while considering absolute contraindications and the patient’s goals of care. The patient’s rapid resolution of pain and normalization of ECG demonstrate successful reperfusion.

AI is a crucial tool, but not a replacement, for clinical decisions

The Queen of Hearts found no OMI (with low confidence) on the first ECG with the wandering baseline.

Smith: every time I put the image through the Queen, it gives OMI with low confidence. Any slight change in the image (cropping, cropping or including the rhythm strip, angle of photo, etc) can result in small changes in the output (I obtained these with different methods on this ECG, and the results were 0.46, .0.56, 0.57, 0.58, and 0.76. A value above 0.50 gets output of OMI. 0.50-0.67 is low confidence)

If clinical decision making had been based solely on the first AI interpretation this could have been missed. But I was concerned about a subtle South African flag pattern with high clinical pre-test likelihood, especially in comparison to the old ECG and with corresponding POCUS findings, and a repeat ECG that showed more clearly reciprocal changes (identified by the Queen of Hearts on the second ECG). OMI is not defined by the ECG, and AI does not replace Bayesian reasoning; the OMI paradigm provides a clinical approach including pre-test likelihood, advanced ECG and AI interpretation, and POCUS.

Clinical Pearls:

- Don’t trust the machine

Automated “pericarditis” interpretations are common in subtle OMI. Always read in context, and know that pericarditis is a diagnosis of exclusion. - Continuously re-calculate probability

History, serial ECGs, echo, +/- troponin: each data point refines your certainty and threshold for action - Act on the synthesis, not one test

Clinical reasoning is Bayesian. When all arrows point toward occlusion, waiting for classic STEMI or an elevated troponin only delays care.

= = =

======================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (11/3/2025):

Superb review by Drs. El-Baba and McLaren of all the reasons why today’s patient does not have pericarditis — but instead had acute LAD occlusion that fortunately was recognized in timely fashion and optimally treated.

- I focus My Comment on the KEY initial decision point — which regards interpretation of the initial ECG.

===

The Initial ECG is Diagnostic!

For clarity in Figure-1 — I’ve reproduced and have labeled today’s initial ECG. As were Drs. El-Baba and McLaren — I was immediately concerned the moment I saw ECG #1. While seeking out this patient’s baseline ECG (from a few years prior) and the repeat ECG (done shortly after ECG #1) served to confirm LAD occlusion — I think it important to emphasize that immediately on seeing ECG #1 in this 60-year old woman with new-onset 10/10 CP (Chest Pain) — a diagnosis of acute OMI can be made until proven otherwise.

- My “eye” was immediately drawn to lead V2 (within the RED rectangle in Figure-1). Especially given the hint of a tiny r wave in lead V1 — the finding of a Q wave in lead V2 is not “normal”. In this patient with new CP — I therefore interpreted the ST-T wave in lead V2 as hyperacute until proven otherwise (The T wave being taller and “fatter”-at-its-peak, as well as wider-at-its-base than expected).

- For me — confirmation of T wave hyperacuity in lead V2 was forthcoming from the subtle-but-real ST elevation in leads I and aVL (Despite some baseline wander in lead I — that fact that the J-point is elevated in all 4 of the QRST complexes in this lead tells us that this ST elevation is real — especially given ST elevation with a straight baseline in neighboring high-lateral lead I).

- High-lateral lead ST elevation and inferior lead reciprocal ST depression tend to be seen principally in proximal LAD occlusions. Therefore, despite the artifact in leads III and aVF — I interpreted the unmistakeable ST segment flattening with slight depression in these 2 leads as enough “final support” in this patient with new 10/10 CP to justify prompt cath, or in today’s case prompt thrombolysis.

- I thought each of the 6 leads that I added question marks to in Figure-1 — manifested less reliable but still suspicious ST-T wave changes (ie, disproportionately “bulky” T waves — or ST straightening or depression). Taken together — I thought 11/12 leads on this initial ECG in this patient with 10/10 CP were either suspicious, or clearly abnormal.

- P.S.: The rhythm in ECG #1 is sinus tachycardia at 105-110/minute. This adds to our concern — as uncomplicated acute OMIs are usually not associated with tachycardia unless infarction is extensive and/or there is heart failure of “something else” going on.

= = =

Figure-1: I’ve labeled the initial ECG in today’s case.

= = =

= = =