Written by Jesse McLaren

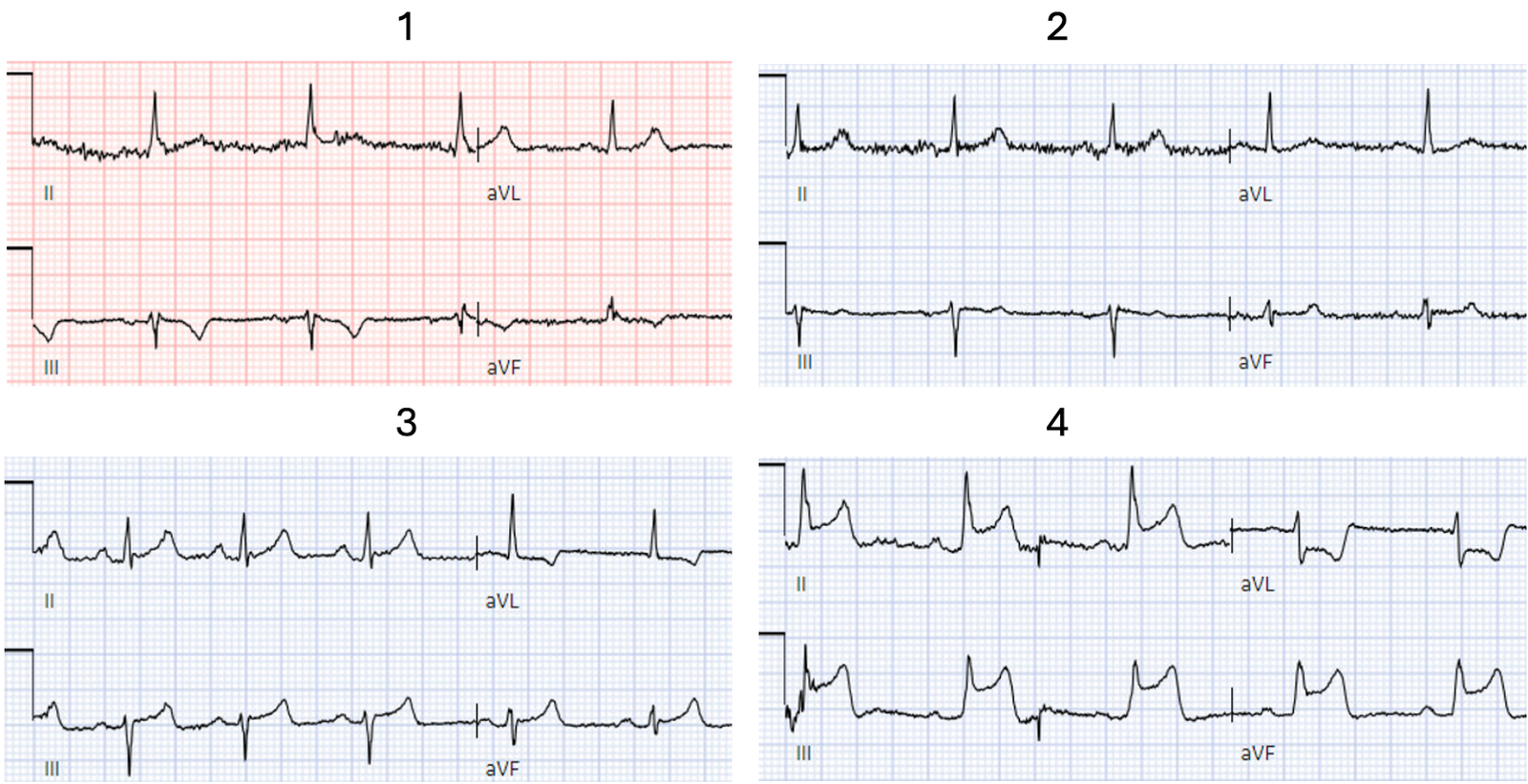

A 45-year-old presented with 24

hours of intermittent chest pain. Below are serial ECGs focusing on the

inferior leads and aVL. Can you guess the sequence?

First, what’s the

interpretation of each ECG on its own?

#1

There’s T wave inversion in

III/aVF and a taller T wave in aVL and V2. On it’s own this is nonspecific, but

in the right context this could be diagonal occlusion (if active chest pain) or

infero-posterior reperfusion (if resolved chest pain).

#2

Normal ECG

#3.

There’s discordant T wave

inversion in aVL, which is reciprocal to inferior T waves that are tall

relative to the QRS but not bulky. On it’s own this is nonspecific, but in the

right context this could be inferior OMI (if active chest pain) or reperfused

high lateral (if resolved chest pain).

#4.

Obvious infero-postero-lateral STEMI(+)OMI, regardless of context

Now let’s put them in order:

what was the sequence?

The most likely would be #2)

initially normal, then #3) subtle OMI, then #4) obvious STEMI, and then #1)

reperfusion:

In other words, the patient with

an initially normal ECG develops an acute coronary occlusion, with ECGs that

progress from subtle to obvious, and then reperfuse after angiography. But

that’s not always the case.

Now let’s look at the actual

sequence, with the addition of clinical context, and see how the patient was

managed:

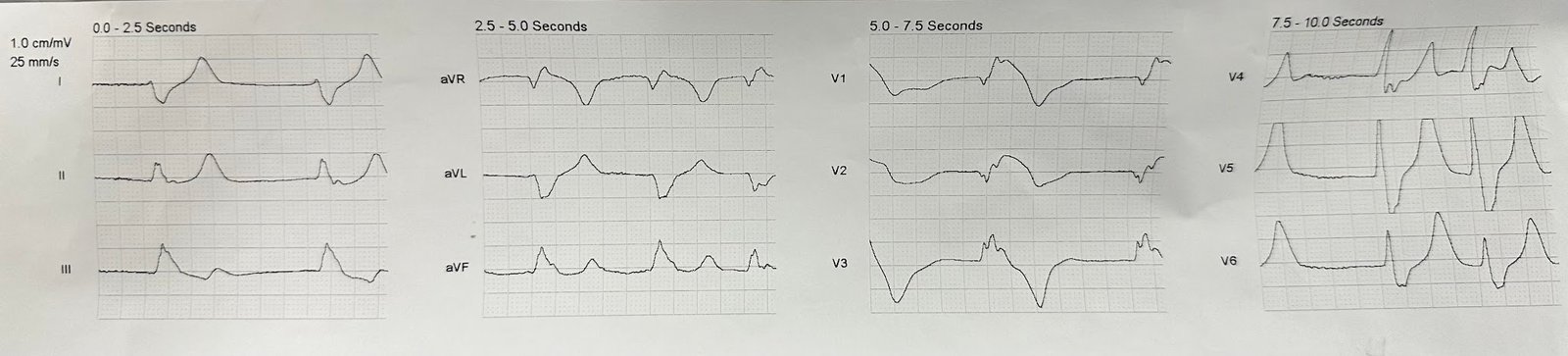

The patient received aspirin from

EMS and arrived at triage painfree (ECG #1). But 90 minutes later troponin

returned at 70ng/L (normal <26 in males and <16 in females), and a repeat

ECG was done (ECG#2) for recurring chest pain. The patient received nitro but the

pain persisted, and the ECG was repeated 10 minutes later (ECG#3). The patient

received more nitro, but the pain continued, and another ECG was done just 6

minutes later (ECG#4).

So the patient arrived with

spontaneous reperfusion(ECG#1). When the pain recurred the ECG normalized(ECG#2),

but this is pseudonormalization: the coronary artery has spontaneously

reoccluded, and the T waves are on their way up. Just 10 minutes later the

repeat ECG showed subtle OMI(ECG#3), with rising T waves and reciprocal STD in

aVL. Looking at each ECG in isolation and without clinical context, the Queen

of Hearts called the first 3 ECGs ‘not OMI’. But in sequence and with the

clinical context of resolved and then recurring and refractory chest pain, the

ECGs show subtle spontaneous reperfusion progressing to reocclusion. With

serial ECGs that are ‘STEMI negative’ the physician could have waited for

serial troponin levels or referred the patient as “non-STEMI”. But with ongoing

pain despite nitro and dynamic subtle ECG changes, a fourth ECG was repeated

just 6 minutes later, showing obvious STEMI(+)OMI (ECG#4), and the cath lab was

activated.

What was the outcome and final diagnosis?

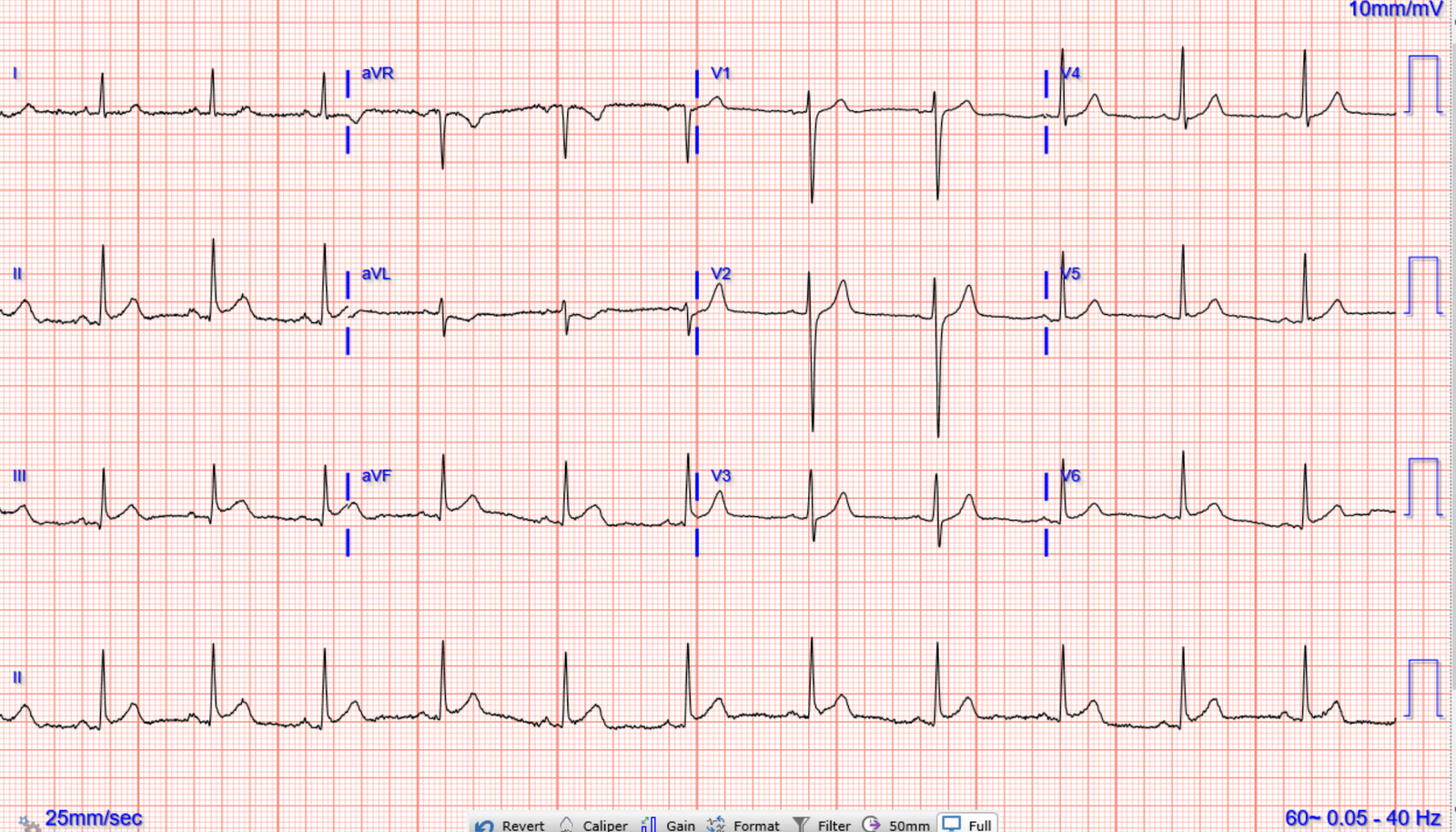

By the time of angiography 20

minutes later the RCA had spontaneously reperfused again: it was 90% occluded

and had normal TIMI 3 flow. The patient had a 5th ECG after

angiography, which was normal (this time truly normalized, not

pseudonormalized):

Post-cath trop was 300ng/L but was

not repeated after. There were no follow up ECGs, which would have shown infero-posterior

reperfusion TWI like the first ECG.

The discharge diagnosis was STEMI

based on the STEMI positive ECG and code STEMI activation, with culprit lesion

on angiography. This is one of the 20% of true positive STEMI that have open

artery and normal flow by the time of the angiogram, showing that STEMI

paradigm does not require a totally occluded artery at angiography.

And yet

more than a quarter of ‘non-STEMI’ have an occluded coronary artery on delayed

angiography, and yet are still discharged with a diagnosis of ‘non-STEMI’. So

neither STEMI ECG criteria nor angiographic findings on their own sufficiently

identify the pathology of acute coronary occlusion. Whereas the OMI paradigm

incorporates, ECG, troponin, echo and angiographic findings to capture the

dynamic nature of occlusion/reperfusion.

If acute MI is a movie, what

film are we watching?

ECGs are 10 second snapshots in

time, and with 4 columns on a page each lead only shows 2.5 seconds – so these

are like still shots from a movie. The angiogram is a longer shot but does not

represent the entire movie, and is separated in time from when the earlier scenes when the initial ECG

was done. But if MI is a movie, what film are we watching?

In the STEMI paradigm there are

only two possible films, which are completely different from each other:

‘STEMI’ depicts on artery that is totally occluded until it is reperfused on

emergent angiography, while ‘non-STEMI’ shows a non-occluded artery that can

wait to be seen on delayed angiography. But many STEMI spontaneously reperfuse

while many ‘non-STEMI’ have totally occluded arteries. Bizarrely, the STEMI/Non-STEMI

films are named not after how they end (the patient outcome) but how they begin

(whether ECGs meet STEMI criteria, or whether code STEMI is activated), with

STEMI(-)OMI still called ‘non-STEMI’ regardless of outcome. This is like

categorizing a film that ends in tragedy as a comedy based on an earlier scene.

Occlusion MI is a dynamic process

that can fluctuate between occlusion, spontaneous reperfusion and spontaneous

reocclusion. Each patient with acute MI has their own film (with Non-occlusive

MI, or Occlusion MI with or without spontaneous reperfusion or reocclusion), presents

at a different time in the show (with acute or subacute presentations), and

have corresponding ECGs that show subtle STEMI(-)OMI, obvious STEMI(+)OMI, or

no ECG signs of OMI at all (for NOMI or electrocardiographically silent OMI).

All these scenes can be missed by STEMI criteria, but looking through the lens

of OMI allows us to see much more. By interpreting each still shot, looking at

their sequence, and applying them in context, we can piece together the film

for each patient.

Take away

1. OMI is a dynamic process that

may spontaneously reperfuse or reocclude, and all phases can be missed by STEMI

criteria

2.Just as true positive STEMI

may have normal flow by the time of the angiogram, OMI is not based exclusively

on the angiogram but also incorporates ECG, echo and trop

3. Serial ECGs applied in

context can show subtle changes from reperfusion (resolved chest pain with

reperfusion T wave inversion) to spontaneous reocclusion (recurring chest pain

with pseudonormalization), and reciprocal change is often the more obvious initial change

4. Acute MI is like a film and

ECGs are still shots: interpreting each ECG still shot through the lens of OMI, looking at their sequence and applying them in context, can help show each patient’s film and at

what stage you are watching

![]()

===================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (6/7/2024):

===================================

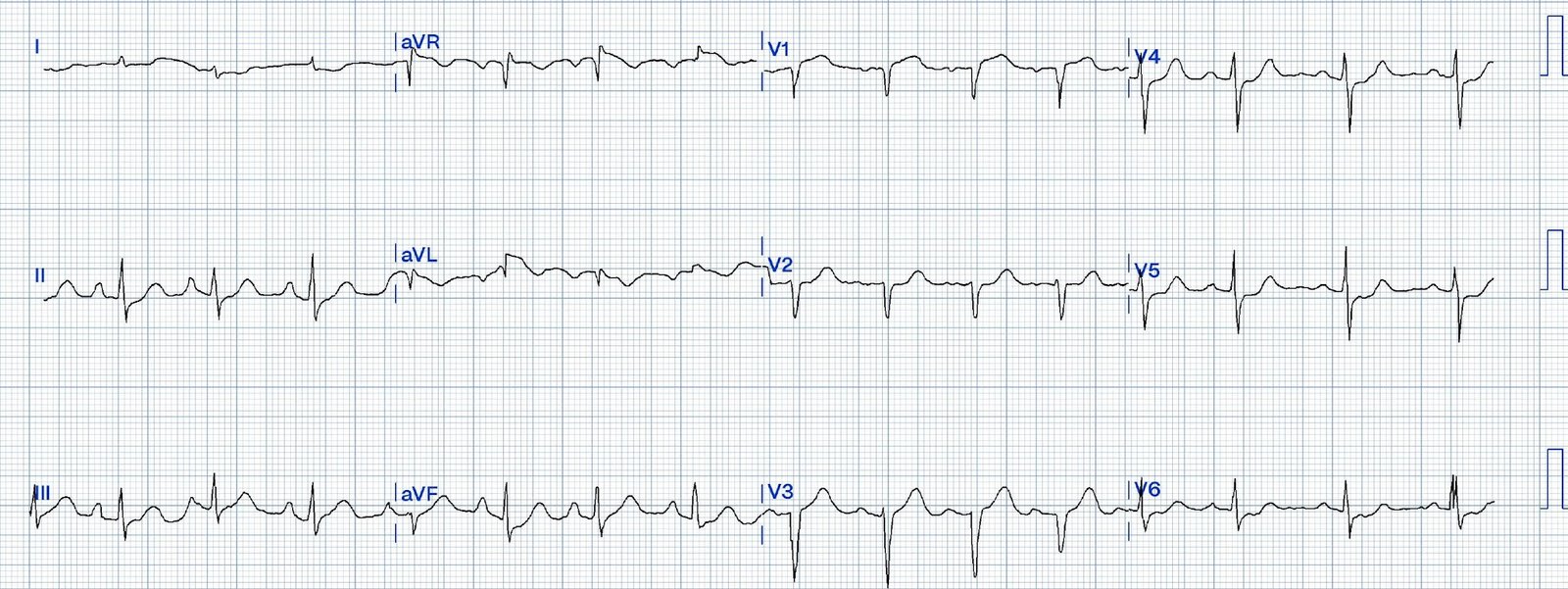

Fascinating clinical dissection of today’s case by Dr. McLaren! My thoughts as I read his excellent discussion are simple — namely, that depending on the history (ie, depending on the presence and relative severity of chest pain at the time each of the 4 ECGs shown was done) — a different logical sequence for these 4 tracings could have been proposed!

- For example — the ECG showing inferior lead T wave inversion would logically occur after chest pain resolves (because this ECG is showing reperfusion T waves) — but whether this ECG was the 1st, 2nd, 3rd or 4th tracing in the sequence might depend on when this sequence of recorded ECGs began (ie, Had this patient’s CP already resolved by the time EMS arrived on the scene to record their 1st ECG — or was CP slowly increasing — or maximal – or gradually or rapidly decreasing at the time that EMS arrived?).

The BOTTOM Line in Today’s CASE:

Realistically — Optimal clinical ECG interpretation is not an attainable goal in the absence of correlation to the presence and relative severity of CP at the time each serial ECG is done. Despite this clinical reality — all too many clinicians still fail to document the presence and relative severity of CP at the time each serial ECG is recorded.

- As is shown in expert fashion by Dr. McLaren throughout his discussion of today’s case — the result is that too many ECGs are erroneously interpreted as “nonspecific”, and too many acute OMI’s are either overlooked or diagnosed only after significant (avoidable) delay.

- Correlating events (symptoms) at each point in the story (ie, at the time each ECG is recorded) — is essential for appreciation of “dynamic” ST-T wave changes that expedite early recognition of an OMI in progress.

- SUGGESTION: There is a very simple way to ensure that this critically important correlation between the presence and relative severity of symptoms to each ECG that is done in a patient with chest pain is not lost: Simply write down for every tracing — on the actual ECG recording on a scale from 0-to-10, what the patient’s “pain score” is at that time. Then sign this notation, and write down the time.

- Adherence to this simple suggestion will instantly facilitate review of serial tracings — and make it so much easier to “put together” a cohesive story that will invariably enhance clinical interpretation.