Written by Magnus Nossen

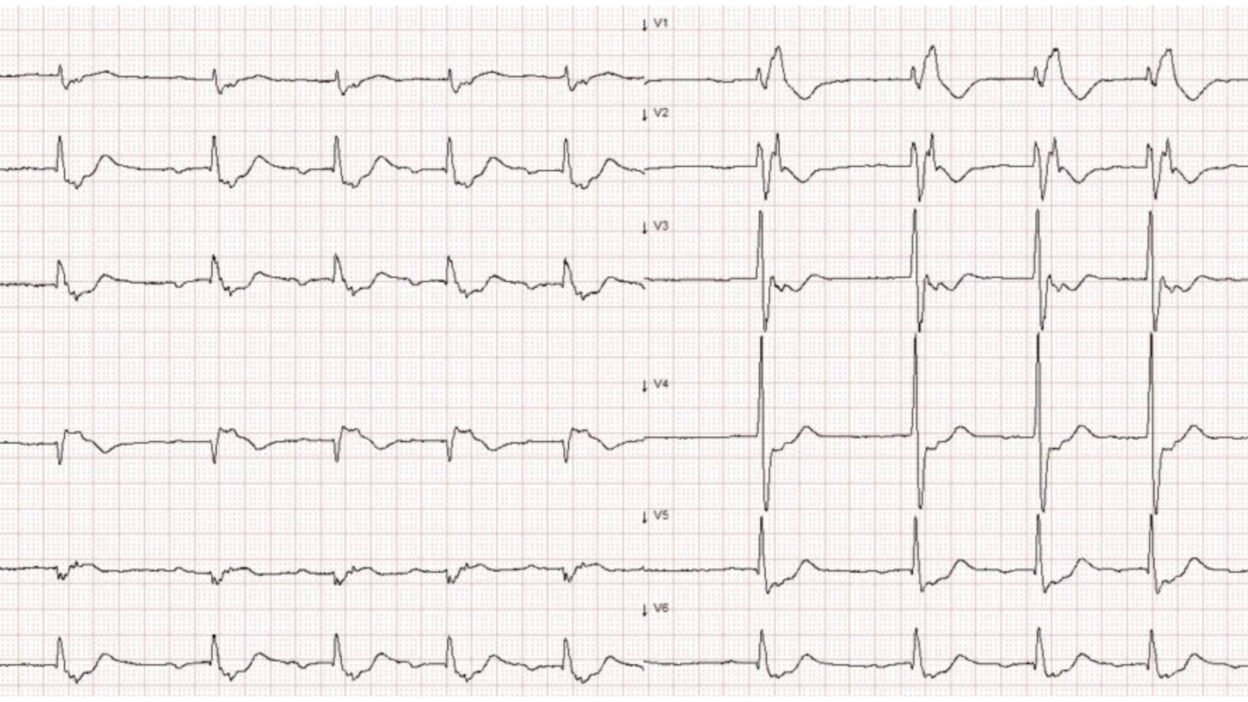

A 70-year-old man experienced sudden onset of palpitations and nausea while at rest. He immediately called EMS. Upon EMS arrival he was alert with GCS 15, denied chest pain and could inform the paramedics that he has a history of mechanical heart valve placement and multiple prior cardiac surgeries. An ECG (shown below) was obtained and transmitted to local ED which was a five-minute drive away. On arrival in the ED, his respiratory rate was 28/min, oxygen saturation 90%, and blood pressure 112/73 mmHg. He appeared diaphoretic. How would you manage this patient?

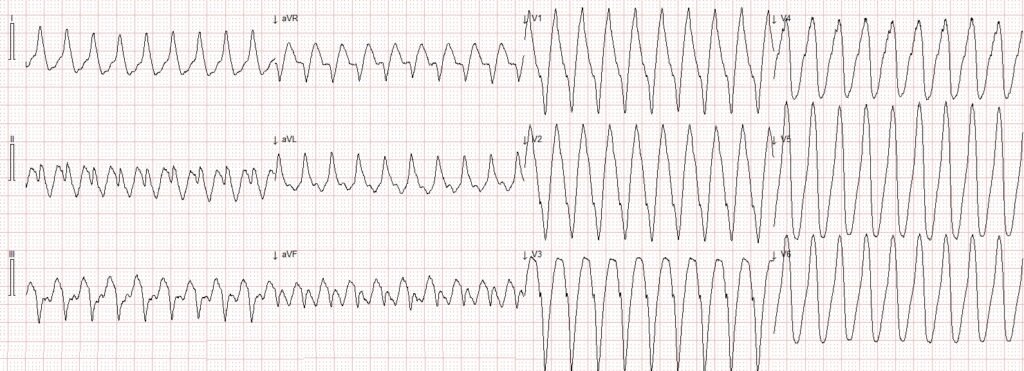

ECG # 1

This patient is clearly hemodynamically compromised with low oxygen saturation and diaphoresis. Best option is to urgently electrically cardiovert.

If possible, as in this case, a 12-lead ECG should always be recorded prior to cardioversion in order to LATER make a diagnosis after cardioversion.

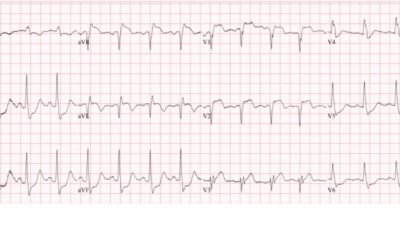

This ECG documenting the arrhythmia has already been obtained and can be scrutinized at a later point in time. The patient was sedated and successfully cardioverted. After cardioversion, the patient stabilized quickly with the repeat ECG shown below.

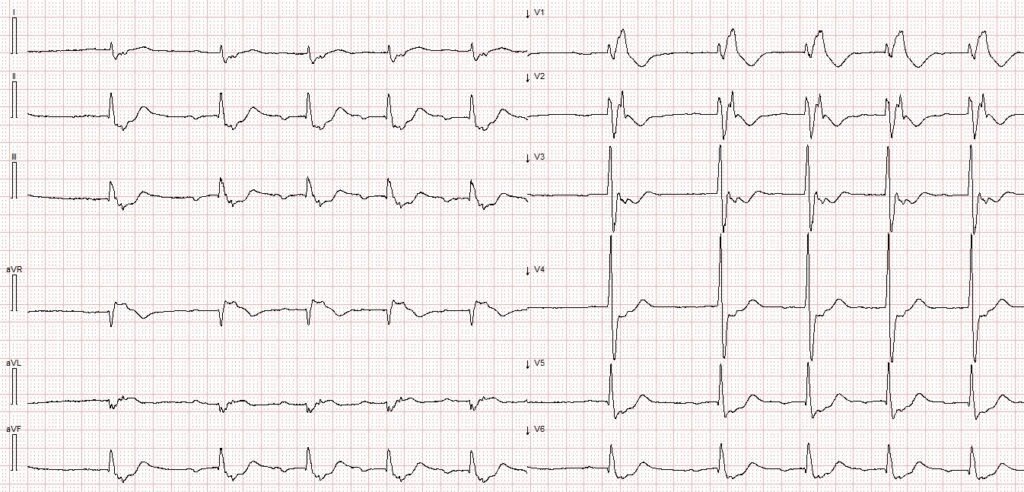

ECG # 2

Now after the patient is stabilized, there is time to have another look at the presenting ECG and the post conversion ECG.

Interpretation ECG #1. The initial ECG in today’s case shows a WCT. The heart rate is aproximately 200 beats per minute. QRS complexes are negative in leads III and aVF, close to biphasic in lead II and positive in leads I and aVL. This gives an axis toward the left shoulder, perpendicular to lead II.

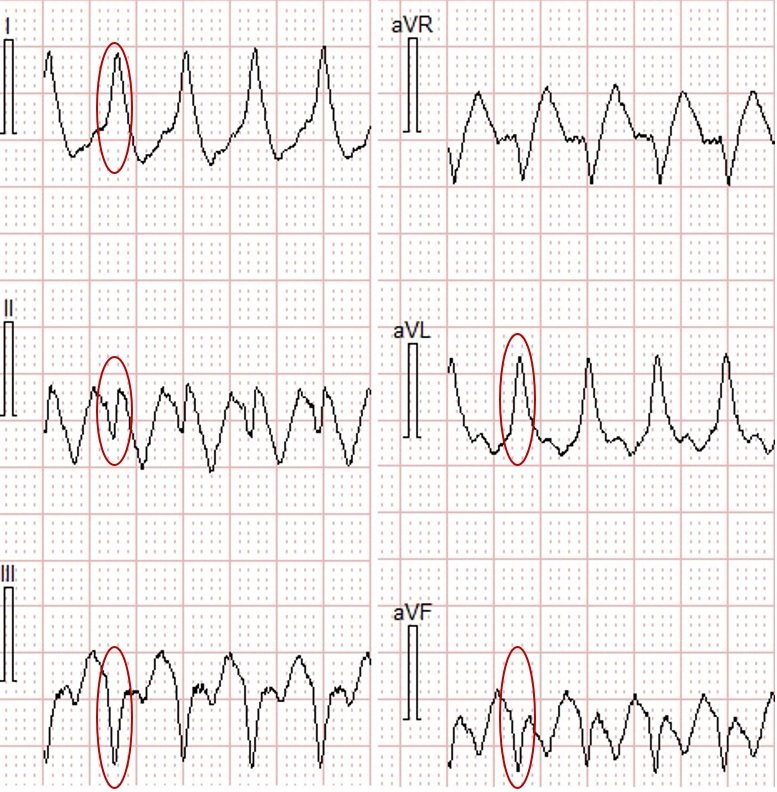

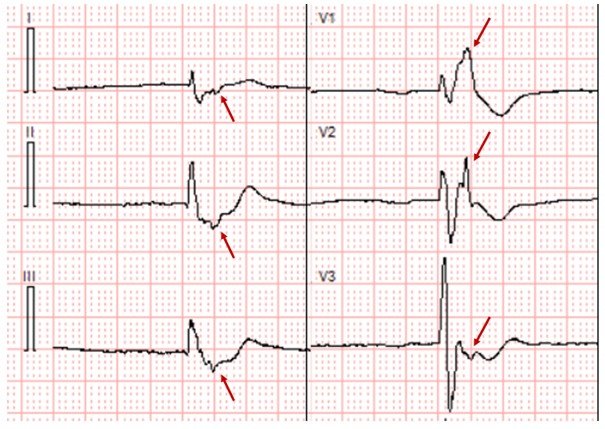

Limb leads from WCT

During the WCT, in the precordial leads there are QS-waves in the right-sided leads (V1-V2) (indicating that it depolarizes from right to left, and thus is initiating in the right ventricle), and R-waves in the lateral leads (I, aVL V5-V6), with the QRS manifesting an LBBB-like morphology. Putting the QRS axis and morphology together — the WCT seen in ECG #1 is consistent with ventricular tachycardia originating from the inferior part of the right ventricle.

There are several different causes of WCT originating from the RV. The most common cause is RVOT VT. In RVOT VT there is an inferior axis, which we do not see in today’s case. For an example of RVOT VT — have a look at this case. Because the axis is NOT inferior, it is very unlikely that this is RVOT VT.

Let us have another look at the ECG following cardioversion. Below I have reproduced ECG #2. What do you see?

Interpretation ECG #2 The first QRS is likely to be a junctional escape beat. For the remaining ECG, there is clearly atrial activity before each QRS. There is an RBBB conduction pattern and borderline right axis deviation. The RBBB is not, however, typical in appearance. In every lead there are not-so-subtle deflections toward the end of the QRS. This deflection is most easily appreciated in lead V2. In the figure below, red arrows mark what I believe to be epsilon waves in leads V1-V3, as well as in leads I, II and III.

Excerpt from ECG #2

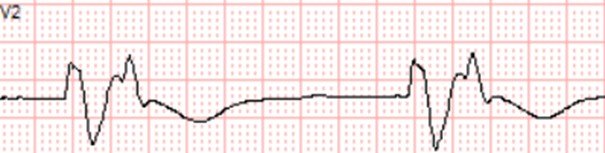

Lead V2 (50mm/s)

Clinical course: The patient had an uneventful hospital stay. Echocardiography showed a chronically dilated RV Outflow Tract, mechanical pulmonary prosthetic valve, VSD patch with a small residual VSD, and a dilated and dysfunctional right ventricle. The echocardiographic findings were consistent with prior examinations. A dual-chamber ICD was implanted, and the patient will continue to undergo regular follow-up in accordance with established protocols for adults with congenital heart disease (ACHD). It is likely that he has developed ARVC phenocopy.

Discussion: This patient was born with Tetralogy of Fallot (ToF), a congenital heart defect composed of ventricular septal defect, pulmonary stenosis, overriding aorta, and right ventricular hypertrophy. Patients with ToF typically undergo staged corrective heart surgery during childhood. Over time, due to pressure and/or volume overload — the RV might dilate and develop fibrosis which together with surgical scarring may lead to arrhythmic subtrates.

Some patients following corrective surgery of ToF may develop a clinical syndrome marked by right ventricular failure, ventricular tachycardia, and epsilon waves on the ECG. This condition is referred to as ARVC phenocopy, reflecting an acquired arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy that mimics the familial form seen in genetic ARVC.

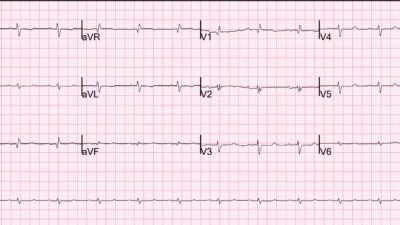

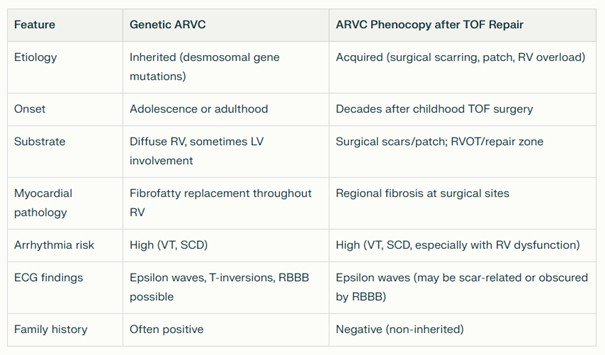

ARVC phenocopy usually appears decades after intial surgery in ToF patients in the absence of familial gene mutations. (See Figure 1 for a comparison between genetic ARVC and ARVC Phenocopy).

Figure 1

For an extensive review on arrhythmias following ToF Surgical repair this article is excellent. For more examples of ventricular tachycardia seen in ARVC have a look at these three cases:

Palpitations and presyncope in a 40-something

A young lady with wide complex tachycardia

Young man with syncope while riding a bike

Learning points

- ARVC phenocopy is an uncommon cause of epsilon waves and ventricular tachycardia.

References:

Krieger, E. V. et al. (2022). Arrhythmias in Repaired Tetralogy of Fallot: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, 15(11), https://doi.org/10.1161/hae.0000000000000084

= = =

======================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (12/13/2025):

I found today’s case by Dr Nossen serves as a powerful reminder to us of a series of important concepts in emergency care. These include:

- That the initial ECG in today’s case is almost certain to be VT (greater than 90-95% statistical likelihood), with this being a conclusion we can arrive at within seconds because: i) This patient is “older” (70 years old); — ii) This patient has known heart disease (The patient telling the paramedics he has had heart valve replacement + multiple prior heart surgeries); — and, iii) The amorphous QRS morphology during the presenting regular WCT rhythm ( = Wide-Complex Tachycardia) not resembling any known form of conduction defect, and with “extreme” axis deviation (all negative QRS complex in lead aVF) is strongly predictive of VT.

- The above said — today’s case reminds us that optimal treatment of a fast (~200/minute in today’s case) regular WCT in a patient with signs of hemodynamic instability — is immediate cardioversion without need to consider potential causes until after the patient has been converted to a normal rhythm. As per Dr. Nossen — this KEY concept was appreciated in today’s case, with successful conversion to sinus rhythm accomplished in timely fashion!

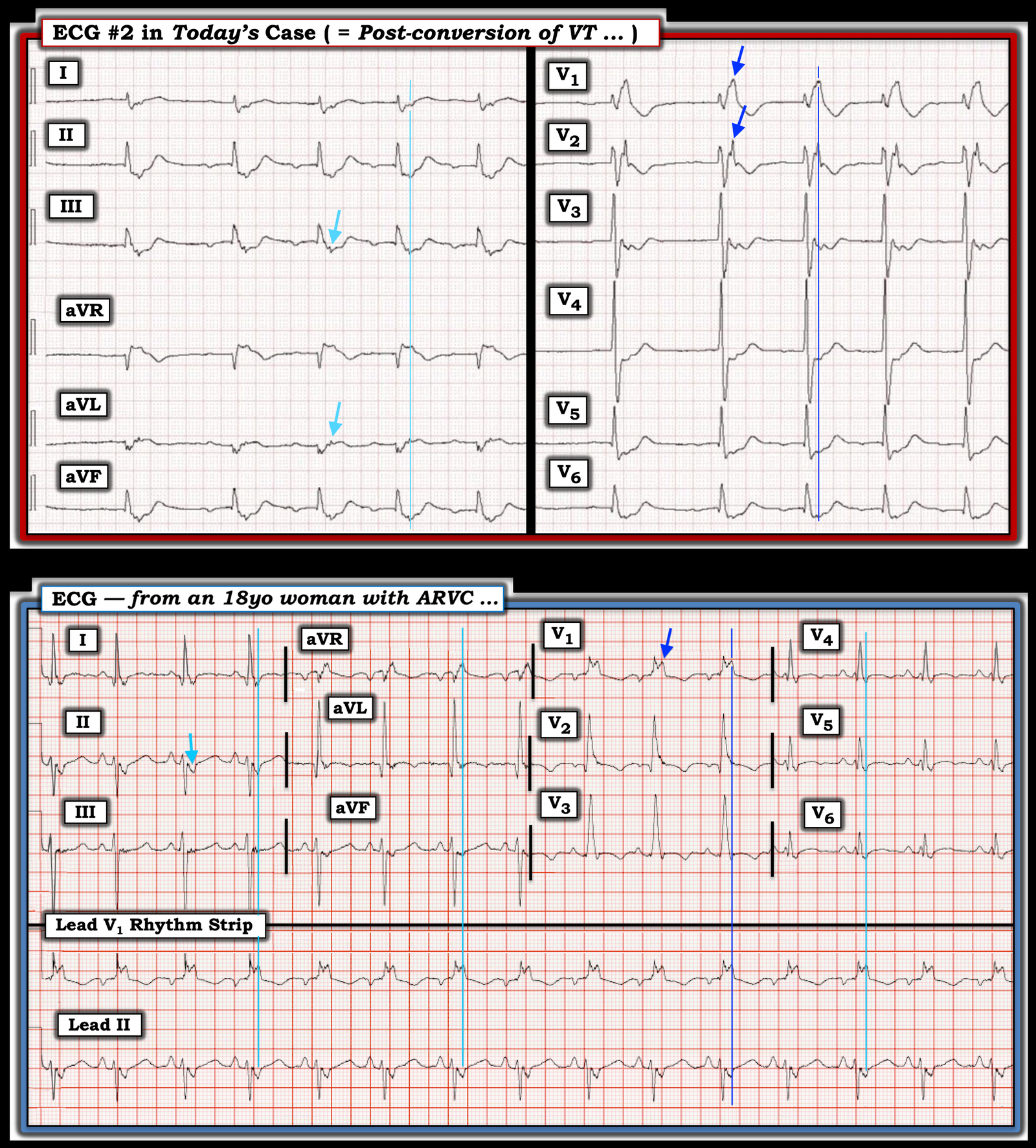

- In addition to the history (of valvular disease and multiple prior cardiac surgeries) — the post-conversion ECG (which I’ve reproduced and labeled below in Figure-1) provides further clues to the etiology of this patient’s VT.

- Adult emergency care providers will continue to see an increasing number of emergency cardiac conditions in adults with CHD (Congenital Heart Disease).

- Epsilon waves do exist — and not only in patients with ARVC (Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy).

= = =

Adults with “Congenital” Heart Disease

Tremendous progress has been made in recent decades in the field of Congenital Heart Disease. Consider the following:

- Today — 97% of children born with CHD will survive until adulthood — and 70% of those alive at 18 years, will live to age 70 (as was the case for today’s patient). As a result — there are now more people over the age of 20 with CHD than under that age! BOTTOM Line: We all will continue to see an increasing number of adults who present for acute cardiac problems as a result of CHD (Dellborg: Circulation 149:1397-1399, 2024 — and — Moodie: Tex Heart Inst J: 38(6):705, 2011).

- To cite the above Dellborg reference — ~60% of CHD is mild (ASD; VSD; pulmonary stenosis) — ~30% is moderate (coarctation of the aorta; Tetralogy of Fallot; aortic stenosis; Ebstein anomaly) — and ~10% are complex cases (single ventricle; pulmonary atresia; transposition of the great arteries). A surprising increase in survival to adulthood is now seen even with many of the most serious complex CHD cases.

- With this increased longevity of CHD patients of all severities — comes the challenge of managing these patients who face substantial increased risk from being predisposed to developing heart failure, coronary disease, endocarditis, stroke — and especially supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias (as in today’s patient).

= = =

The Post-Conversion ECG: Epsilon Waves …

Epsilon waves are not common. I never saw them during my 30 years as a primary care Attending, despite interpreting all outpatient ECGs for 35 providers, as well as many of our in-patient ECGs (or at least — I did not recognize any Epsilon waves that may have passed my way). Even now, in the 15+ years since I retired from academics and receive tracings that puzzle emergency providers from all over the world — my experience seeing actual cases with Epsilon waves is few and far between.

- The reason for my lack of experience seeing Epsilon waves outside of the medical literature is twofold: i) Epsilon waves are rare! — and, ii) Even when patients are encountered who have Epsilon waves — they are often (usually) not recognized because of either technical shortcomings in the ECG recording process that are overlooked — or the provider(s) are uncertain about how to recognize an ECG finding that is so rare (See My Comment at the bottom of the page in the June 3, 2023 post — in which I review the importance of filter settings and use of the special Fontaine lead system to optimize the chance of detecting Epsilon wave deflections)

- NOTE: Many of the examples of Epsilon waves that I have seen in articles or textbooks show this finding as a subtle, low-amplitude deflection that appears after the QRS complex in no more than a few selected leads. It is for this reason that today’s post-conversion ECG is that much more remarkable — because it features Epsilon waves that are not small in amplitude, and which are seen in multiple leads (Upper tracing in Figure-1).

- What caught my “eye” in the post-conversion ECG is how very wide the QRS complex looks (significantly more than 1 large box in duration in lead V1 = well over 0.20 second, as per the BLUE arrows in leads V1,V2 in Figure-1). A “QRS duration” of over 0.24 second in a patient without some underlying toxicity seemed too long to be only the result of QRS prolongation — therefore our supposition of some other type of waveform deflection (ie, an Epsilon wave).

- To clarify the timing of “extra” deflections seen in other chest leads — I drew a vertical dark BLUE line through this most easily identifiable positive Epsilon wave deflection at its peak in lead V1 — and a vertical light BLUE line through the Epsilon wave in the limb leads. But as noted by Dr. Nossen — Epsilon waves may be seen in association with conditions other than ARVC = ARVC Phenocopy, in which regions of late ventricular activation may be seen not only with CHD (such as corrected Tetralogy of Fallot, as in today’s patient) — but also in other infiltrative cardiomyopathies, such as cardiac Sarcoid (Omotoye et al: JACC Case Reports 3(8): 1097-1102, 2021).

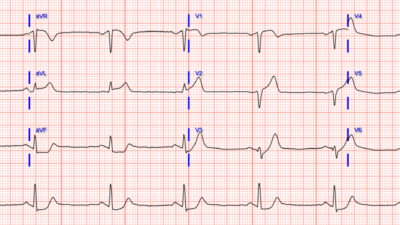

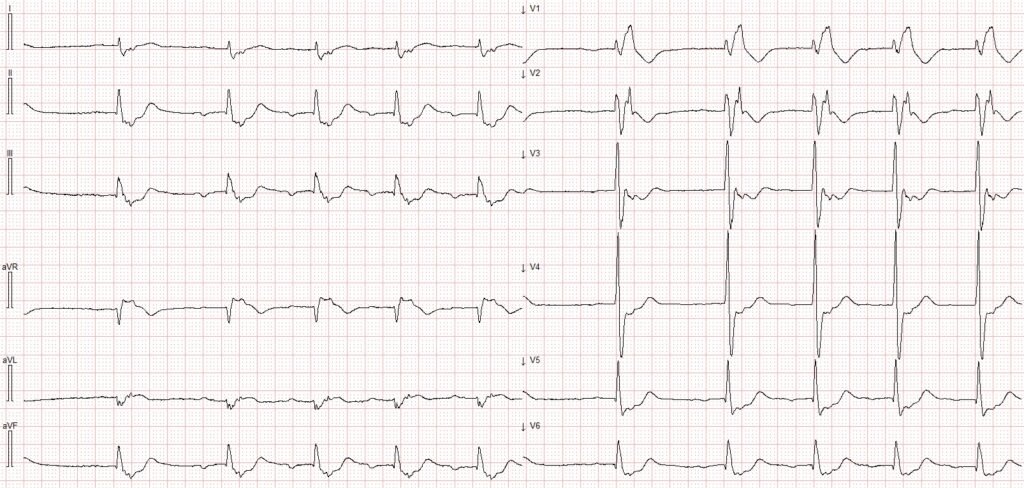

- By way of comparison — I’ve added the ECG from an 18-year old woman with documented ARVC to Figure-1, in which we see similarly huge Epsilon waves in multiple leads (this case taken from HERE). Seeing these 2 examples of huge Epsilon waves restores my faith that this is a real finding that we need to be looking for (especially in the post-conversion 12-lead ECG after resolution of sustained VT) — realizing that most of the time the Epsilon waves that we may observe will not be as prominent as they are in Figure-1.

= = =

Figure-1: Comparison of today’s post-conversion ECG (TOP) — with the ECG of an 18-year old woman with documented ARVC (BOTTOM).

= = =

= = =