Written by Magnus Nossen

Today’s patient is an 80-something male with a history of CABG. Since his bypass surgery years ago, he had not experienced any angina. He had chronic atrial fibrillation managed with oral anticoagulation, and longterm left bundle branch block (LBBB) on his ECG.

After physical activity, he developed abdominal and chest discomfort that persisted despite rest. On EMS arrival, he reported ongoing chest pain. Vital signs were unremarkable, apart from tachycardia at 125 bpm. ECG # 1 was recorded during chest pain.

How would you interpret this ECG? How would you manage this patient considering the described symptoms? — and what do you suspect to be the cause of the ECG changes?

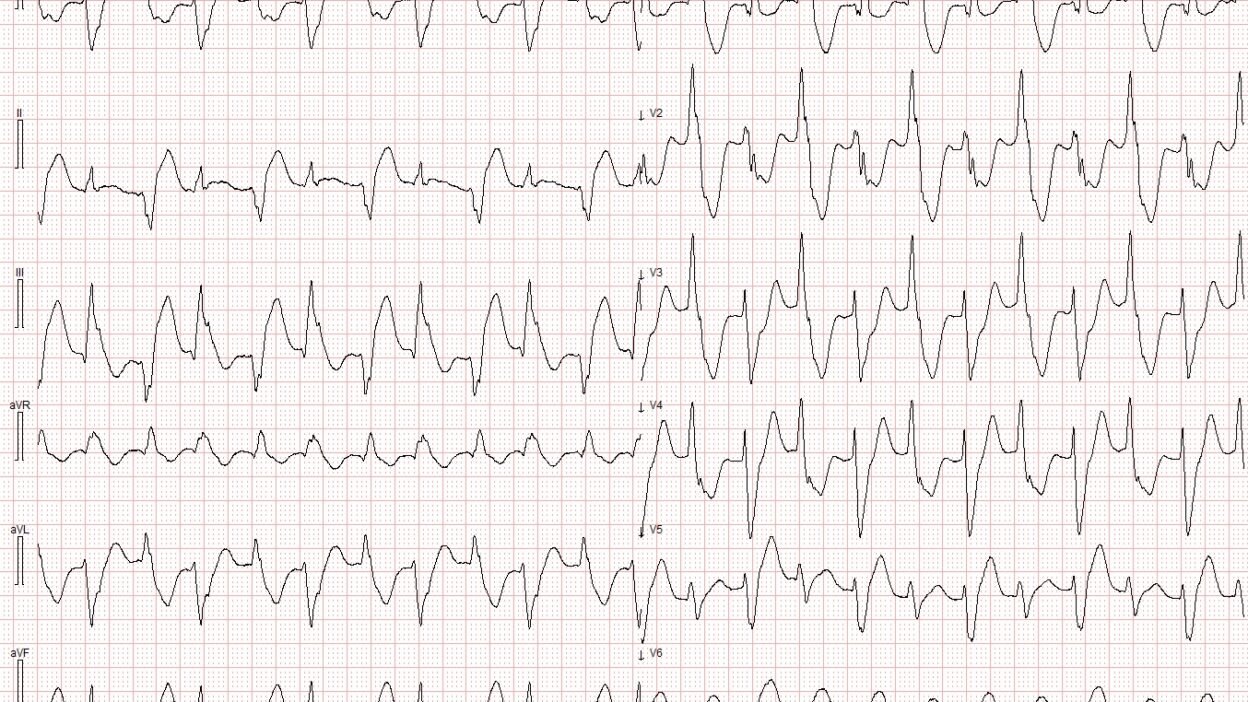

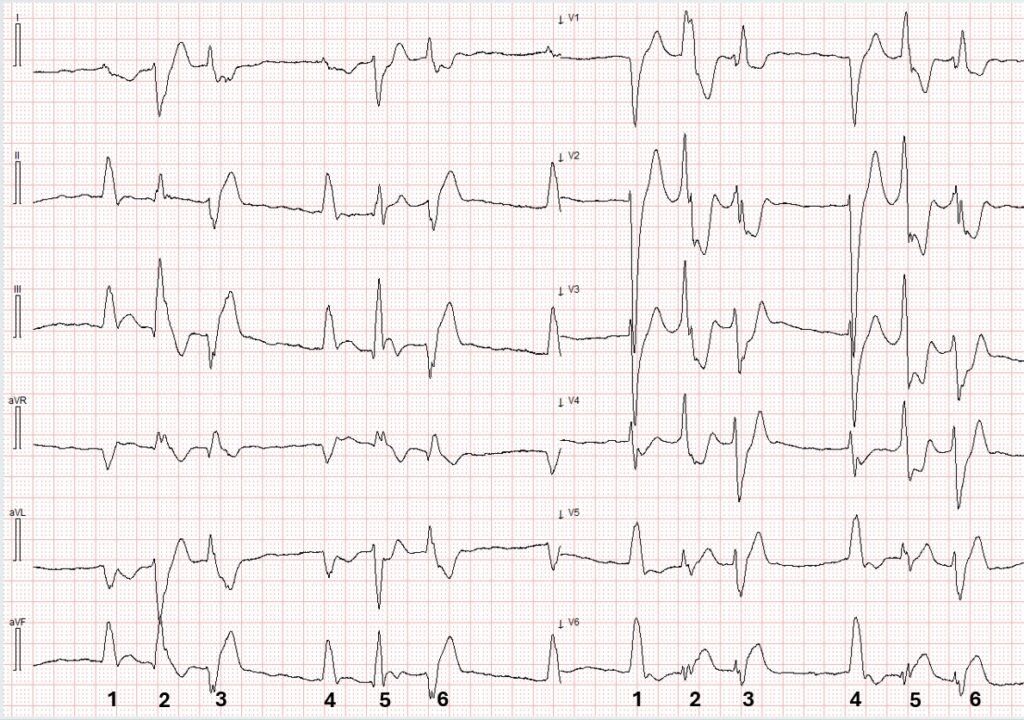

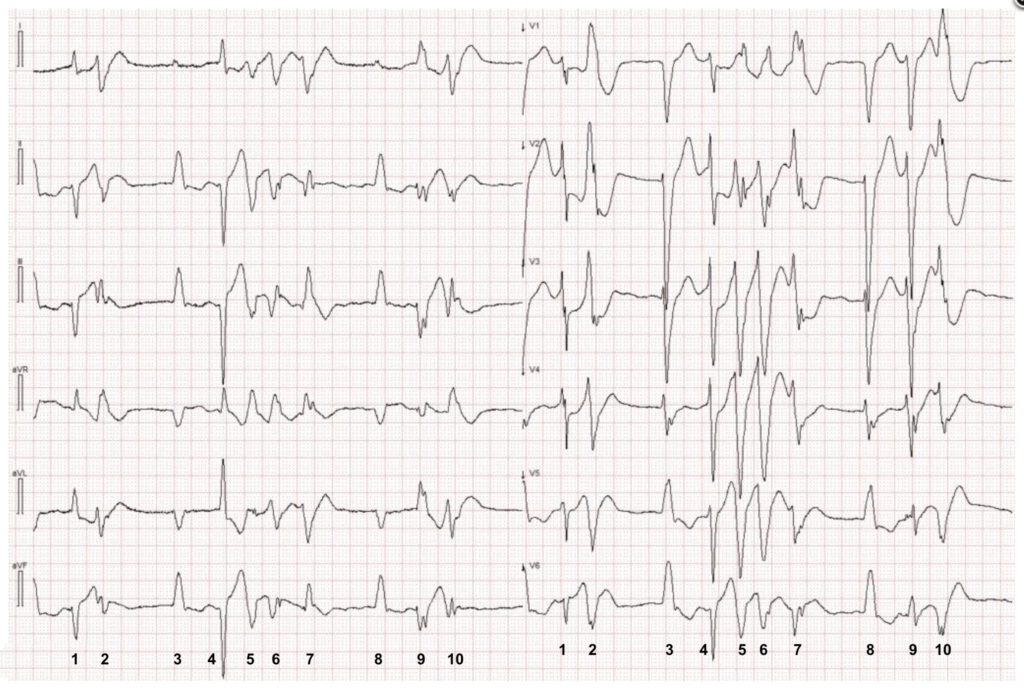

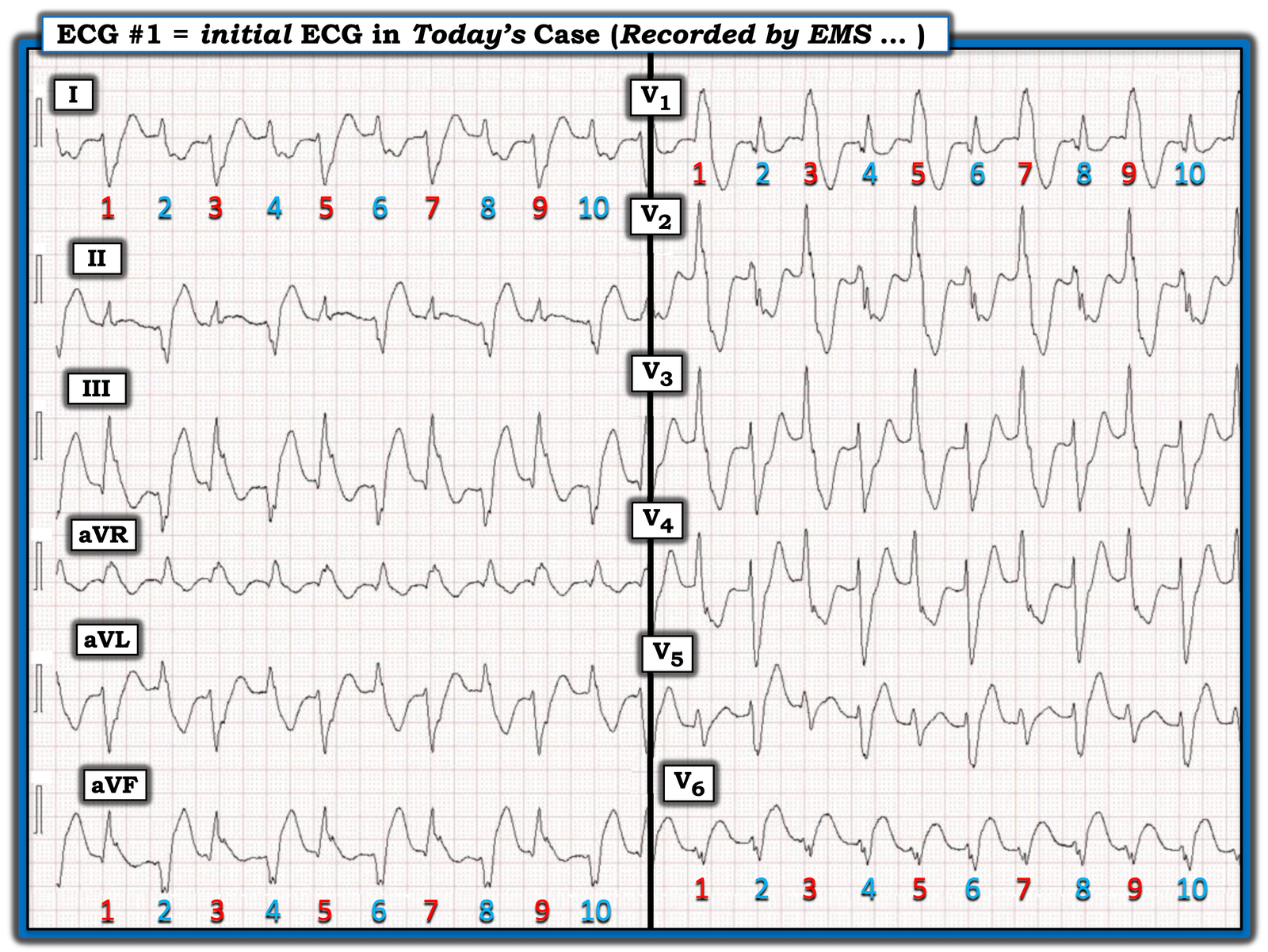

ECG # 1

Standard lead layout, speed 25 mm/s. The precordial and limb leads were recorded simultaneously, so that the first beat in the limb leads corresponds in time with the first beat in the precordial leads

This ECG was interpreted as showing LBBB with bigeminal PVCs.

Do you agree with this interpretation? What is on your list of differential diagnoses and potential causes?= = =

Interpretation: The above ECG shows a regular WCT with two distinct QRS morpholgies. This is not AFib with bigeminal PVCs, as the rhythm is regular. The QRS morphology in the above ECG is not consistent with LBBB (which was described as “baseline” for this patient). Instead, there is RBBB morphology, with an alternating left anterior fascicular block (LAFB) and left posterior fascicular block (LAFB) morphology. This ECG is consistent with bidirectional ventricular tachycardia, at a rate of about 125 bpm.

Of the ventricular tachycardias, bidirectional ventricular tachycardia is by far the least common variant. This rare arrhythmia is typically associated with digoxin toxicity or CPVT. There are other etiologies associated with this arrhythmia such as myocarditis, hypokalemia and even herbal aconite poisoning.

- The patient in today’s case was not on digoxin.

- Patients with CPVT usually present by childhood or early adolescence.

- The arrhythmia seen in today’s intitial ECG persisted for about 10 minutes, then spontaneously terminated. A repeat ECG (below) was obtained following the change in the patient’s rhythm.

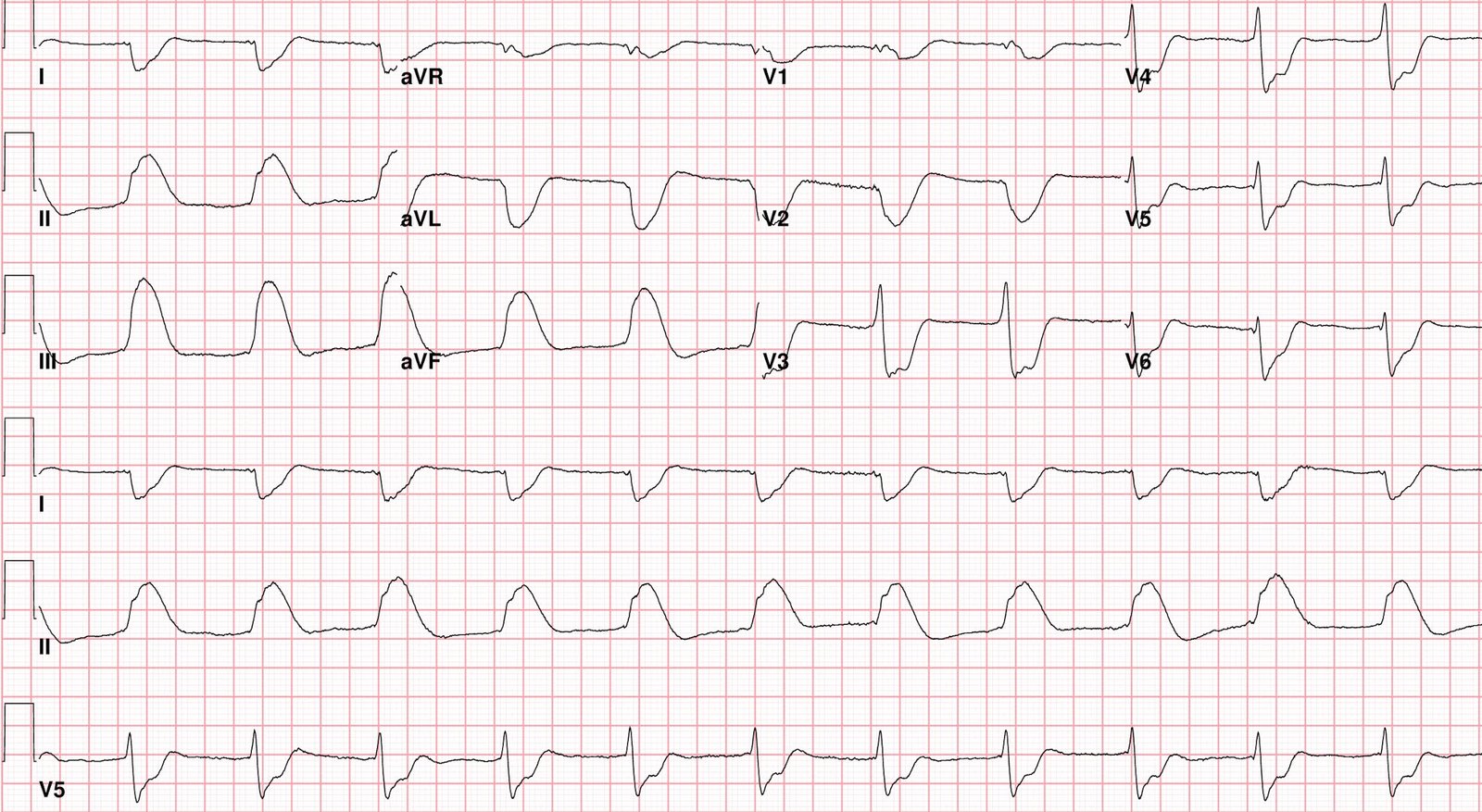

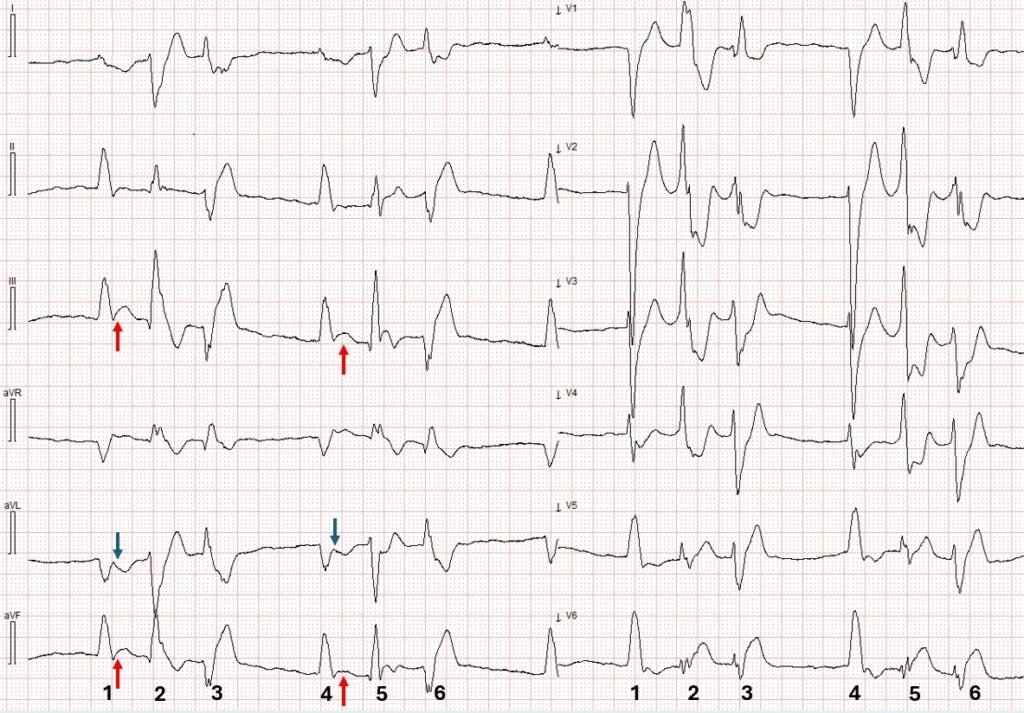

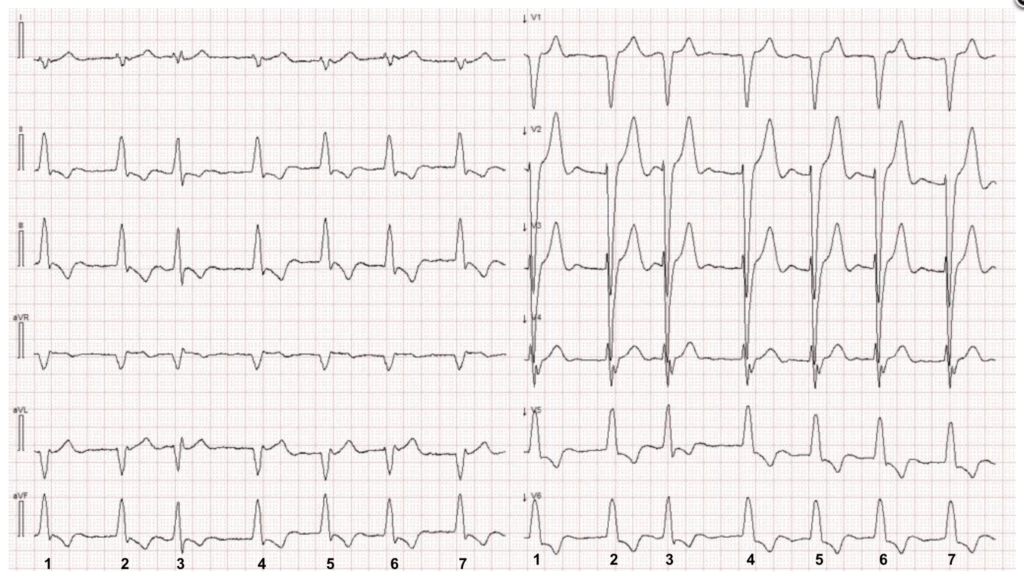

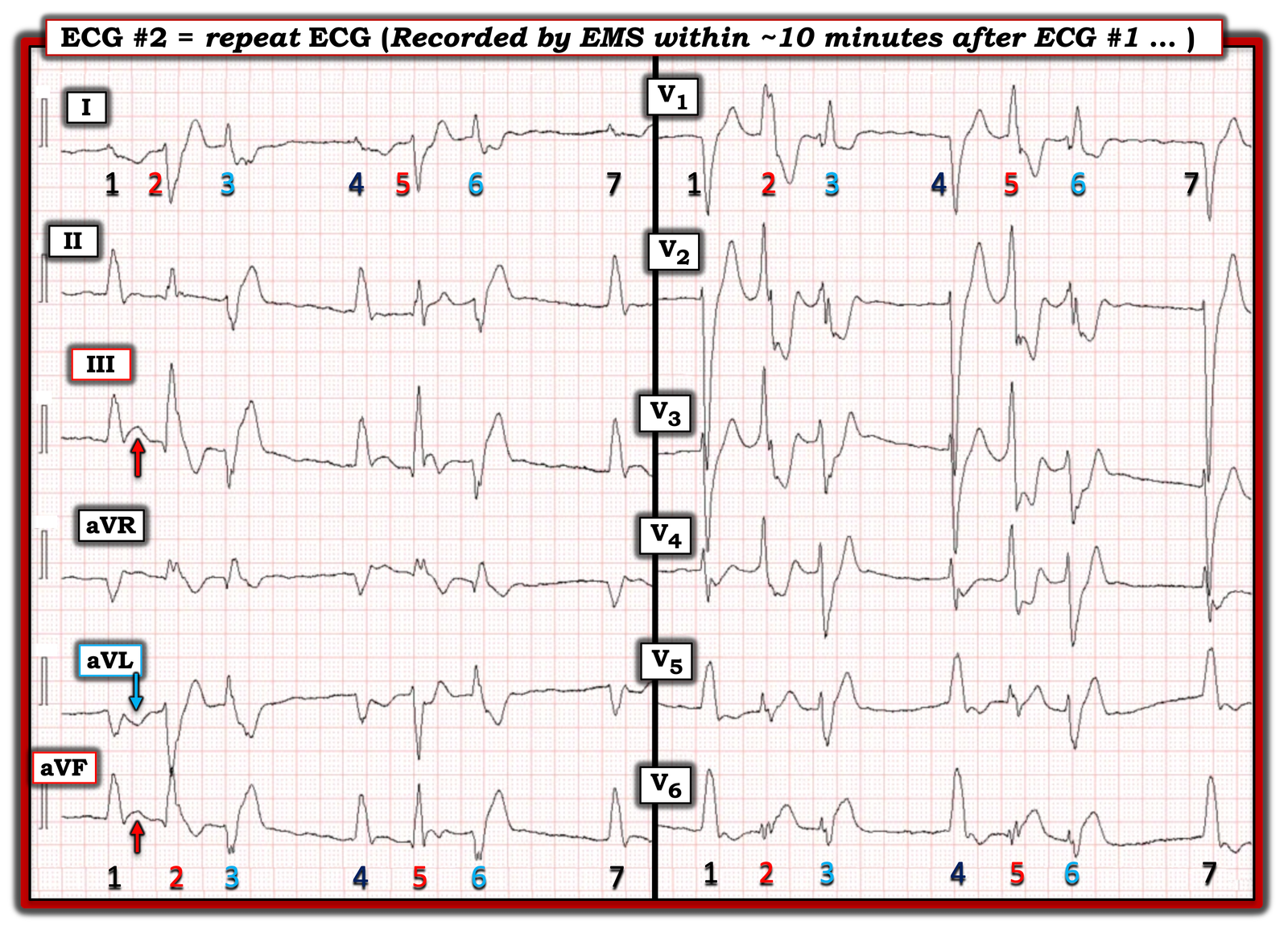

ECG # 2

Paper speed 25mm/s. Precordial and limb leads recorded simultaneously.

The above tracing is very interesting. Have a close look at it — and to try to determine the cause of the patient’s symptoms (as well as the cause of the ventricular arrhythmia that was seen in ECG #1).

Interpretation: ECG #2 demonstrates AFib with frequent premature ventricular complexes (PVCs). Limb leads and precordial leads are recorded simultaneously. Beats #1 and 4 are supraventricular with a LBBB pattern, and they show clear ischemic changes — specifically, concordant ST segment elevation in the inferior leads and concordant ST depression in lead aVL.

Beats #2 and 5 are PVCs with a RBBB/LPFB morphology — while beats #3 and 6 are PVCs with a RBBB/LAFB morphology. These PVCs satisfy the Smith-modified Sgarbossa criteria for OMI in the setting of a wide QRS complex. The PVC morphologies are identical to the ones seen during the Bidirectional VT.

Same ECG as ECG #2. The rhythm is atrial fibrillation with beats #1 and 4 being supraventricular and conducted with LBBB abberancy. Beats #2 and 5 are PVCs with RBBB/LPFB morphology — while beats #3 and 6 are PVCs with RBBB/LAFB morphology. Red arrows point to concordant ST segment elevation and blue arrows point to concordant ST segment depression in natively conducted beats.

In summary, this patient (who has a history of CABG, and is presenting with ACS symptoms) — has ECG findings of ongoing inferoposterolateral Occlusion Myocardial Infarction (OMI) with frequent multifocal PVCs and ischemia-triggered Bidirectional Ventricular Tachycardia!

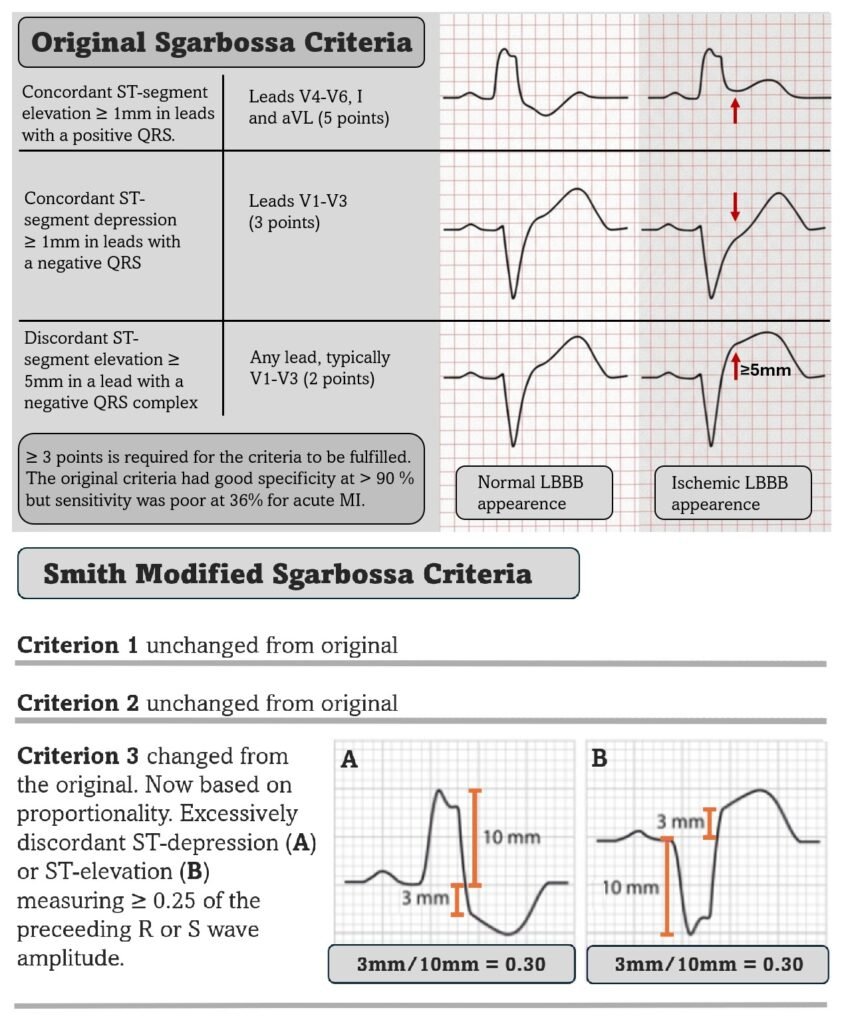

As have been exemplified many times on this blog, just because the QRS complexes are wide does not mean that an ischemia diagnosis is impossible. Drs Smith and Meyers validated the modified Sgarbossa criteria for ischemia in LBBB and paced rhythms. It is likely that the modified criteria are applicable to other wide QRS morphologies as well, especially if very high ST/R or ST/S ratios are present. The image below summarizes the original and modified Sgarbossa criteria

Original and modified Sgarbossa criteria summarized

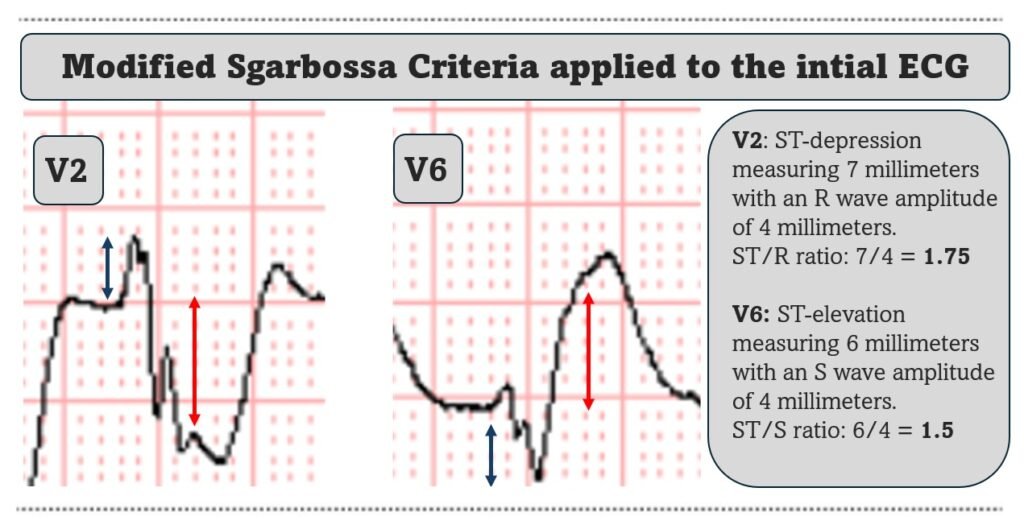

Having a second look at the presentation ECG — in retrospect, ECG # 1 showing Bidirectional VT strongly suggests underlying OMI as the cause of the ventricular arrhythmia. Even though the Smith modified Sgarbossa criteria are not formally studied or validated in VT — the VERY high ST/R and ST/S ratios should alert the clinician to the likely possibility that this Bidirectional VT is due to OMI! The image below shows leads V2 and V6 fulfilling the modified criteria. In fact, the modified Sgarbossa criteria are positive for most leads in ECG #1.

Magnified view of leads V2 and V6 from ECG #1. Applying the Smith-Modified-Sgarbossa criteria gives an ST/R ratio in lead V2 of 1.75 and an ST/S ratio in lead V6 of 1.5 — which is significantly above the threshold value of 0.25. Even though the modified criteria are not validated in VT, a ratio of this magnitude must be assumed to be caused by OMI until proven otherwise.

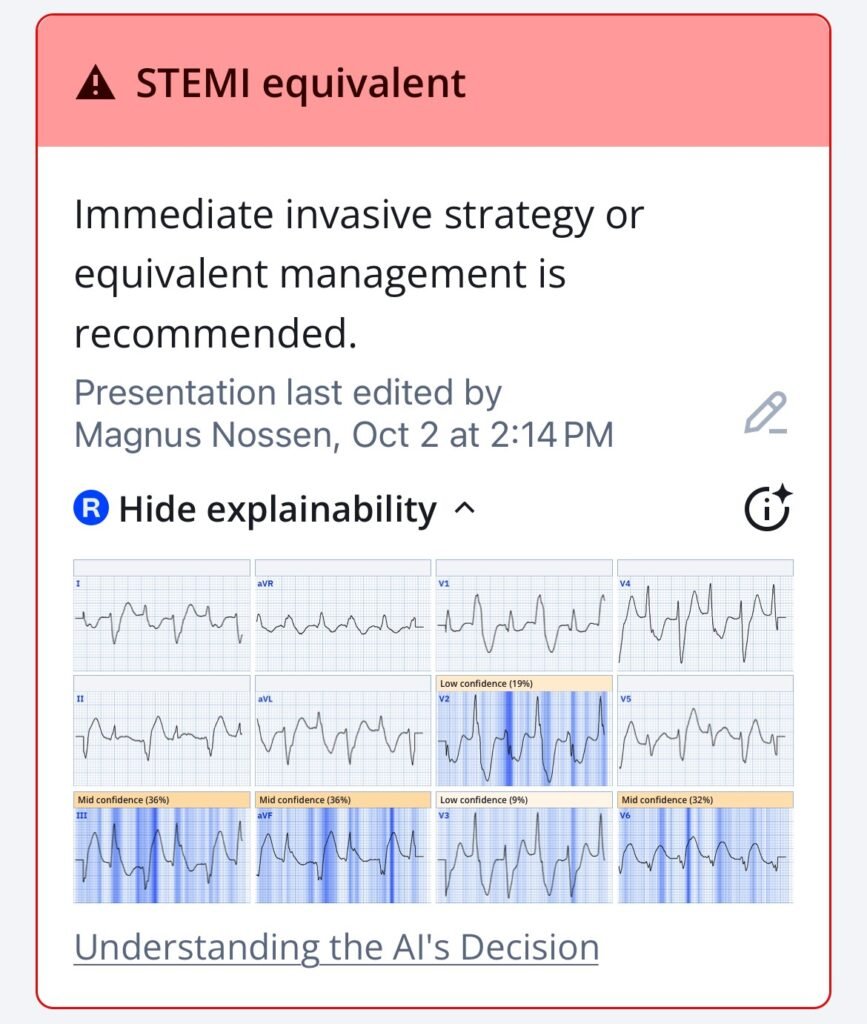

For such a rare presentation of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) — it is impressive that the PMCardio Queen of Hearts AI ECG Model accurately identified the underlying OMI on the initial ECG, and flagged it as a STEMI equivalent. These findings were missed by the interpreter evaluating the initial ECG.

Queen of Hearts interpretation with explainability of the initial ECG in today’s case. The AI model interpreted the rhythm as a wide QRS tachycardia, which is technically correct. Due to the rarity of BdVT, the algorithm is not trained to specifically recognize this arrhythmia.

New PMcardio for Individuals App 3.0 now includes the latest Queen of Hearts model and AI explainability (blue heatmaps)! Download now for iOS or Android. https://www.powerfulmedical.com/pmcardio-individuals/ (Drs. Smith and Meyers trained the AI Model and are shareholders in Powerful Medical). As a member of our community, you can use the code DRSMITH20 to get an exclusive 20% off your first year of the annual subscription. Disclaimer: PMcardio is CE-certified for marketing in the European Union and the United Kingdom. PMcardio technology has not yet been cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical use in the USA.

Case continuation: The patient was given ASA, NTG, and morphine by EMS — and was transported to the local ED. On arrival, the patient’s symptoms had improved some. The below ECG was recorded.

What does this ECG tell us — given the clinical scenario of improved chest pain?

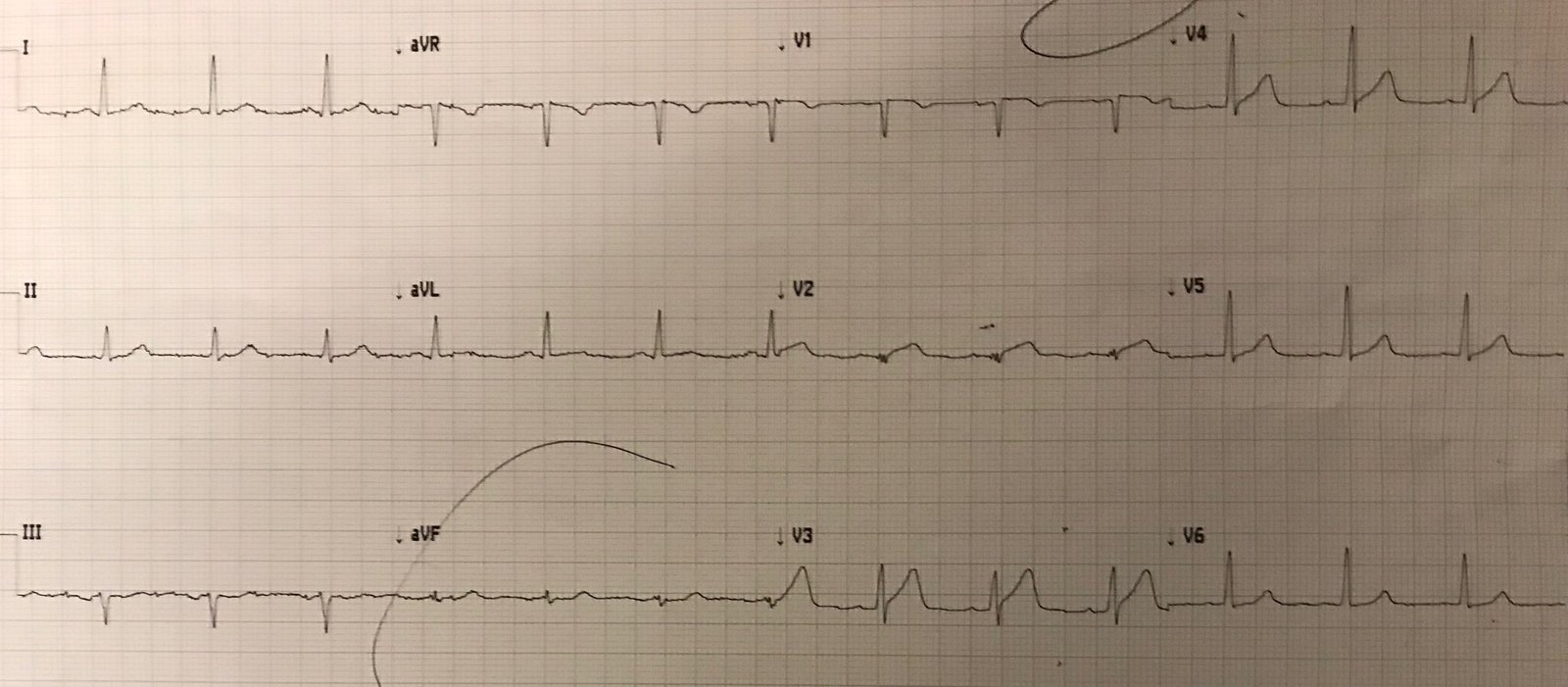

ECG # 3 – in the local ED

Paper speed 25mm/s. Limb leads and precordial leads are recorded simultaneously.

This ECG (ECG #3) demonstrates AFib with LBBB — and episodic runs of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (PMVT). The supraventricular QRS complexes (beats #3 and #8) no longer display concordant ST segment changes, which — together with symptom improvement — suggests some degree of reperfusion. However, the occurrence of PMVT remains a highly ominous finding in the context of this patient’s ACS.

- Troponin was elevated at 237 ng/L (reference <34 ng/L).

- Given the presence of a number of nonsustained episodes of PMVT, persistent albeit improved chest pain, and a positive troponin result — the patient was transferred to a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) facility.

On arrival at the PCI center the patiens was pain free with the below ECG.

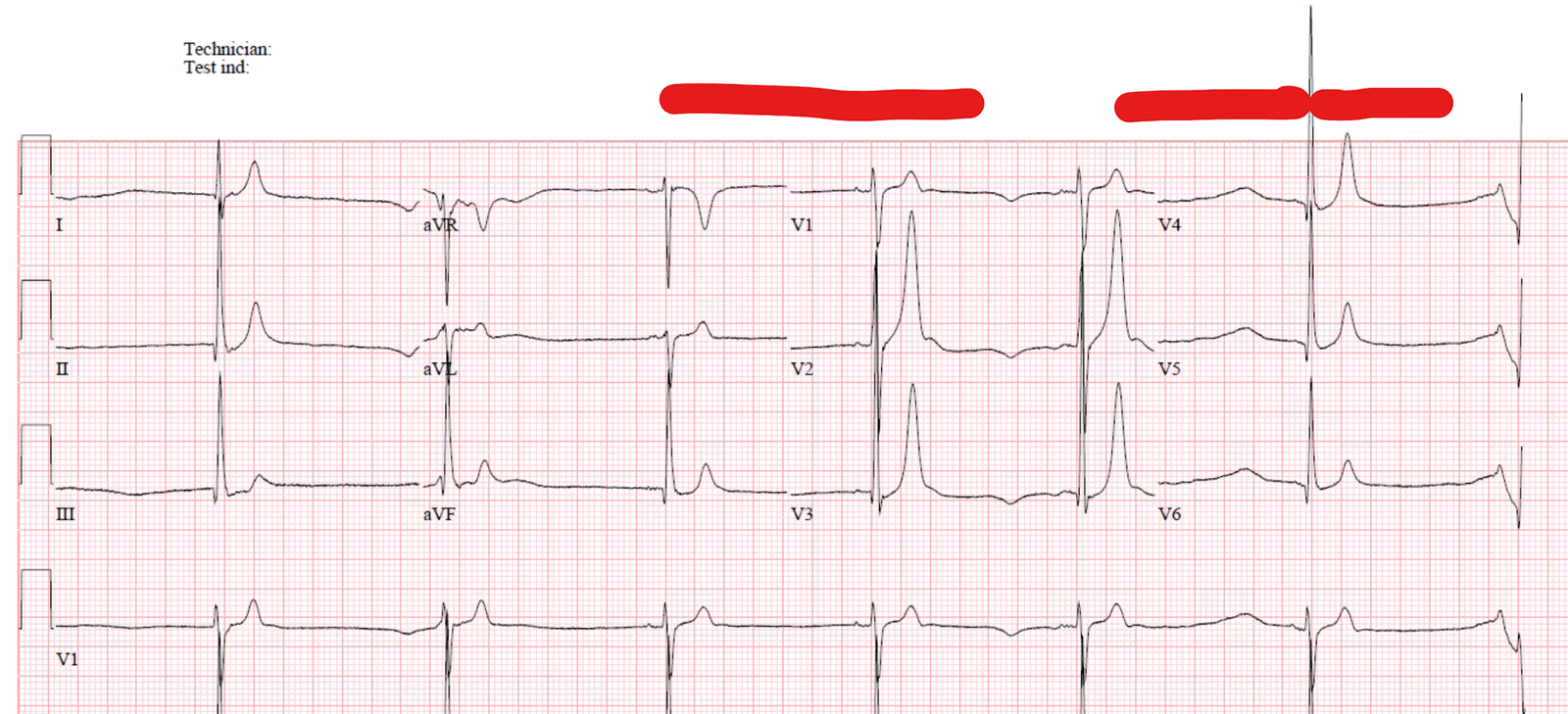

ECG # 4 before PCI

Atrial fibrillation, TWI as a sign of reperfusion. Beat #3 has a slightly different QRS-morphology and QRS-duration which may be due to supernormal conduction or fusion from a PVC occuring at the same time as the natively conducted QRS.

The ECG demonstrates AFib, and an atypical LBBB (Typical LBBB should have monophasic R wave in lead I) and signs suggestive of reperfusion (disproportinately large T wave inversion in the inferior leads, and also in leads V5,V6).

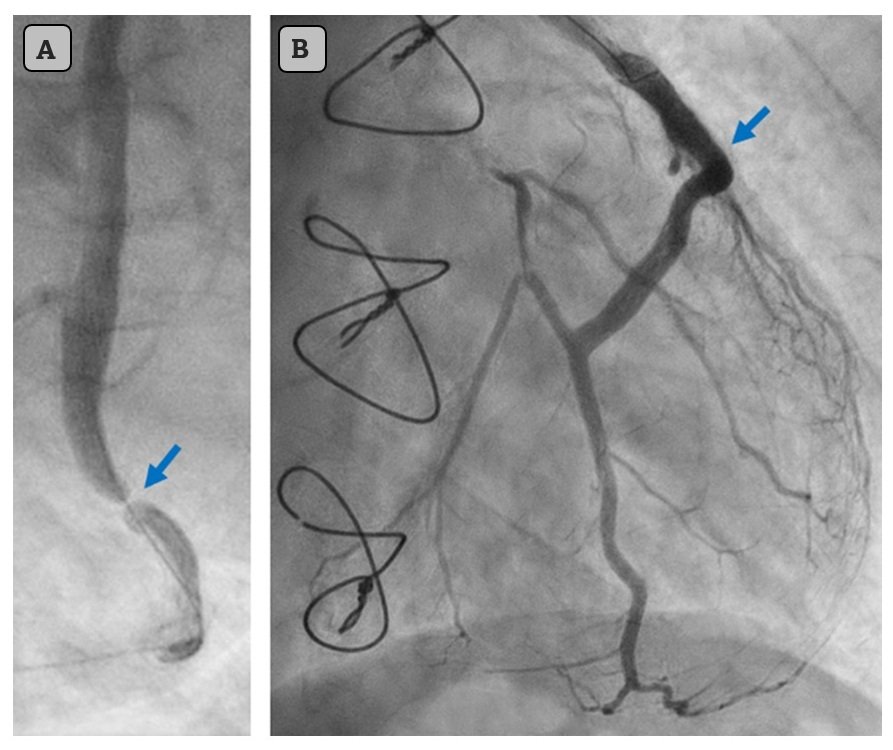

- The patient underwent coronary angiography which revealed native triple vessel occlusion: 100% occlusion of both the proximal left anterior descending artery (pLAD) and proximal right coronary artery (pRCA), as well as distal left circumflex (dLCx). The arterial graft to the LAD and the venous grafts to the RCA and first diagonal were all patent.

Arrows poiting to the culprit lesion before intervention (A) and after stenting (B).

= = =

Outcome of Today’s Case:

The culprit lesion was identified as a 99% subtotal occlusion in the venous graft to a large 2nd marginal branch of the LCx, which was treated with stent placement. Peak troponin I reached 40,758 ng/L, and echocardiography showed a posterolateral wall motion abnormality with an ejection fraction of 39%. Frequent PVCs, but no sustained VT was observed following revascularization. Contemporary heart failure therapy was initiated, including slow-release metoprolol 75 mg twice daily.

Due to frequent PVCs, a 24-hour ambulatory Holter monitor was conducted soon after discharge revealing 6,955 PVCs, 23 triplets, and 3 short episodes (3-5 beats) of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. The average heart rate was 42 bpm, which was associated with significant exercise intolerance. Consequently, the beta blocker dose was reduced — with a follow-up Holter scheduled to reassess ventricular ectopy and heart rate. Following adjustment of the beta blocker, the patient reported improved well-being and better exercise tolerance.

- Then, during the follow-up HOLTER, while wearing the device at home — the patient suddenly became unresponsive. Advanced cardiac life support was initiated and continued for 45 minutes, including multiple defibrillation attempts. Despite all efforts, resuscitation was unsuccessful.

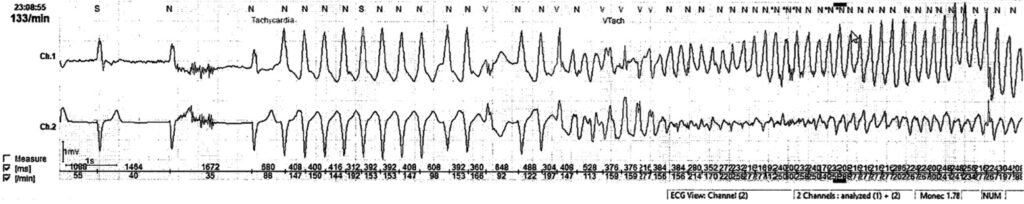

Excerpt from the Ambulatoy HOLTER

A short run of monomorphic VT deteriorating to VF. The arrhythmia was triggered by R-on-T PVC. Unfortunately the patient could not be resuscitated

= = =

Discussion:

Bidirectional VT (BdVT) caused by acute ischemia is extremely uncommon and limited to case reports. That said, as demonstrated in today’s case — this can occur. Clinicians should be aware of this possibility if no other apparent cause of BdVT is evident and the clinical picture supports ACS.

The detailed arrhythmic mechanisms underlying BdVT are outside the scope of this blog. However, like catecholaminergic polymorphic VT and digoxin toxicity — myocardial ischemia can disrupt calcium cycling within cardiomyocytes, giving rise to delayed after-depolarizations and ventricular arrhythmias. Because BdVT will often be resistant to electrical cardioversion — addressing the underlying cause of BdVT is essential for optimal outcome.

In today’s patient — BdVT resolved spontaneously so we do not know if the arrhytmia would have responded to cardioversion. Despite guideline-appropriate management, this patient experienced out-of-hospital cardiac arrest for which resuscitation was unsuccessful. This highlights the unpredictable nature of malignant ventricular arrhythmias — even with appropriate therapy. Noting the tragic outcome, one might question whether there had been an indication for ICD implantation in this octogenarian with ischemic cardiomyopathy and ventricular arrhythmia.

Following revascularization, frequent PVCs were observed, but no sustained arrhythmia occurred. According to current guidelines, ICD implantation in a patient based solely on frequent PVCs and brief nonsustained VT (3–5 beats) is not recommended. Perhaps an argument could be made for placement of a permanent pacemaker to avoid bradycardia and thus be able maintain high dose beta blocker therapy. Such considerations are always clear in retrospect, yet rarely straightforward in clinical practice.

Case report in full:

Case Report – European Heart Journal

= = =

Learning points

- BdVT is most typically associated with Digoxin toxicity or CPVT, but can, as this case illustrates be associated with ACS.

- BdVT is often resistant to electrical cardioversion, as the mechanism is increased automaticity and not re-entry.

- BdVT often responds poorly to antiarrhytmics. As a result — focus on identification and correction of the underlying cause is paramount.

- BdVT seen in CPVT should be treated with beta-blockers and sedation.

- BdVT seen with digoxin toxicity should be treated with digoxin antibody, and maintaining high normal potassium serum levels.

= = =

======================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (2/2/2025):

Today’s case by Dr. Nossen is an utterly fascinating study of multiple confounding QRS morphologies in this patient who was found to have BiDirectional VT.

- PEARL #1: Awareness that limb leads and chest leads have been simultaneously recorded in the series of ECGs presented above by Dr. Nossen — is KEY to appreciation of which QRS morphology belongs to which rhythm.

= = =

What is BiDirectional VT?

As review — it’s good to be aware of the 4 basic types of VT (Ventricular Tachycardia) morphology: i) Monomorphic VT; — ii) Polymorphic VT (PMVT) — which includes Torsades de Pointes; — iii) Pleomorphic VT; — and, iv) BiDirectional VT (BDVT). I review these terms in the June 1, 2020 post of Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog — and limit my comments here to BDVT:

- BiDirectional VT — Of the above 4 morphologic forms of VT that I’ve listed above — BDVT is by far the least common. This rhythm is characterized by beat-to-beat alternation of the QRS axis. It distinguishes itself from PMVT and pleomorphic VT — because a consistent pattern (usually alternating long-short cycles) is seen throughout the VT episode. As implied in its name, there are 2 QRS morphologies in BiDirectional VT — and they typically alternate every-other-beat.

= = =

PEARL #2: It’s important to appreciate how difficult BiDirectional VT may be to recognize! This is because: i) This rhythm is not common (In my experience — it is rare!); — ii) The rate of BDVT is usually rapid (so not easy to determine if P waves might be hiding within T waves, or within the wide QRS complexes!); — and, iii) It is very easy to mistake BDVT for ventricular bigeminy or alternating bundle branch block (as both of these other 2 conditions are much more common than BDVT).

= = =

PEARL #3: When contemplating the diagnosis of BDVT — Consider one of the following conditions which are known to predispose to this arrhythmia:

- Digitalis toxicity

- Acute myocarditis

- Acute MI

- Hypokalemic periodic paralysis

- CPVT (Catecholaminergic PolyMorphic VT ) — Please Check Out My Comment in the July 3, 2025 post for a fascinating case in which BDVT was found in this patient with CPVT!

- Metastatic cardiac tumors

- Some types of Long QT Syndrome

- Herbal aconite poisoning

NOTE: Although acute MI is listed above as one of the conditions known to “predispose” to BDVT — in my experience, it is not at all common to see BDVT as the sole result of acute ischemia — although today’s case provides us with an exception to this generality!

= = =

The Initial ECG in Today’s CASE:

For clarity in Figure-1 — I’ve numbered the beats in this initial ECG with alternating colors. As per PEARL #1 above — there are only 10 beats in this tracing, with the format used providing us the advantage of seeing the QRS morphology for each of these 10 beats in each of the 12 leads!

- At first glance — I did not know what the rhythm was in Figure-1. The overall rate for the rhythm in ECG #1 is obviously fast ( = about 130/minute). The rhythm manifests a repetitive pattern ( = alternating QRS morphology every-other-beat).

- Although I wondered if the “small hump” in the ST segment of each even-numbered beat in lead I might represent some form of atrial activity — sinus P waves were clearly absent ( = We see no upright P wave preceding any of the beats in lead II).

- Confession: Until I numbered the beats and remembered that limb leads and chest leads are simultaneously recorded — I was confused about which beats in the limb leads corresponded to which QRS morphology in the chest leads.

- PEARL #4: When all else fails — GO BACK to the history! The 83-year old man in today’s case has a long history of coronary disease — with notation in the history of an episode of new CP (Chest Pain) — with this patient having longstanding AFib, and with his baseline ECG showing LBBB (Left Bundle Branch Block).

= = =

PEARL #5: Today’s patient was hemodynamically stable in association with the initial ECG in Figure-1. As a result — providers had a moment-in-time to look closer at the rhythm (ie, If the patient would have been hemodynamically unstable — then it would no longer matter what the rhythm in Figure-1 was, since immediate cardioversion would then be indicated).

- To facilitate assessment of the 2 different QRS morphologies in Figure-1 — We can first look at the odd-numbered beats (in RED) — and then at the even-numbered beats (in BLUE).

- All QRS complexes are wide.

- RED-colored beats are consistent with rbbb-lphb morphology.

- BLUE-colored beats are consistent with rbbb-lahb morphology.

- The almost-all-negative QRS complexes for BLUE beats in the inferior leads — and the almost-all-negative QRS complexes in lead V6 for both BLUE and RED beats — suggest that both QRS morphologies are likely to be of ventricular origin!

- And then (as per PEARL #4) — I went back to the history and remembered that today’s patient has been in longstanding AFib with LBBB conduction. Both regularity of the pattern of alternating QRS complexes and the fact that neither of the 2 QRS morphologies at all resemble LBBB conduction (which should never result in predominant positivity of the QRS in lead V1) — strongly suggests that the underlying rhythm is not AFib — and — that both QRS morphologies are of ventricular origin! (See the ADDENDUM below — for more on my “user-friendly” approach to to LBBB,RBBB,IVCD).

- BOTTOM Line: The above sequential deductions led me to the diagnosis of BiDirectional VT (despite what appeared to be the absence of any of the predisposing conditions to BDVT that were listed in PEARL #3).

= = =

Figure-1: I’ve labeled the initial EMS ECG.

= = =

The Repeat EMS ECG:

As per Dr. Nossen, within the next 10 minutes — the rhythm in Figure-1 spontaneously converted to the rhythm in ECG #2.

- For clarity in Figure-2 — I have once again used colored numbers for the 7 beats present to facilitate assessment of QRS morphologies.

- As per Dr. Nossen — the underlying rhythm is now AFib. We see a repetitive pattern of 3-beat groups with different QRS morphologies.

- BLACK-colored beats #1,4,7 — are consistent with LBBB conduction, which we are told is a longstanding conduction defect for this patient ( = predominant negativity for beats #1,4,7 in anterior chest leads — and an all-positive QRS in lateral chest leads V5,V6). Note that although the QRS is tiny for beats #1,4,7 in lead I — the QRS is still all positive in this left-sided lead.

- RED-colored beats #2,5 — are consistent with rbbb-lphb morphology (with essentially the same QRS morphology as for the RED beats in Figure-1).

- BLUE-colored beats #3,6 — are consistent with rbbb-lahb morphology (with essentially the same QRS morphology as for the BLUE beats in Figure-1).

- And as per PEARL #4 — When all else fails, GO BACK to the history in which this 83-year old man reports an episode of new CP as one of the main reasons he contacted EMS.

- PEARL #6: I’ve highlighted with colored arrows in Figure-2 — that leads III,aVL and aVF demonstrate in addition to LBBB conduction — primary ST-T wave changes of acute infarction ( = ST elevation that should not be there in leads III,aVF — and reciprocal ST depression in lead aVL). Not surprisingly — cardiac cath revealed severe multi-vessel disease.

= = =

Final Thought: Among the “Take-Home” Points from today’s case — is that BiDirectional VT occasionally can be seen with ischemia (which today’s elderly patient clearly had given the history of new CP, the elevated Troponins, and cath findings of severe multi-vessel disease).

= = =

Figure-2: I’ve labeled the repeat EMS ECG, recorded after spontaneous resolution of the initial rhythm (ie, within ~10 minutes of ECG #1).

= = =

ADDENDUM:

In the 13-minute video below — I simplify rapid diagnosis of the type of Bundle Branch Block by focus on the 3 KEY Leads ( = leads I,V1,V6 ) — allowing you to distinguish between LBBB vs RBBB vs IVCD — in less than 5 seconds!

- NOTE: You can at any time easily find this video (and other ECG Videos by Dr. Sam Ghali and myself) under the “ECG Videos” tab in the Upper Menu at the top of every page in Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog!

= = =

ECG VIDEO: A user-friendly approach to ECG diagnosis of BBB.

= = =

===