Written by Jesse McLaren

Four

patients presented with chest pain. All initial ECGs were labeled ‘normal’ or

‘otherwise normal’ by the computer interpretation, and below are the ECGs with

the final cardiology interpretation. If you were working in a busy emergency

department, would you like to be interrupted to interpret these ECGs or can these

patients safely wait to be seen because of the normal computer interpretation?

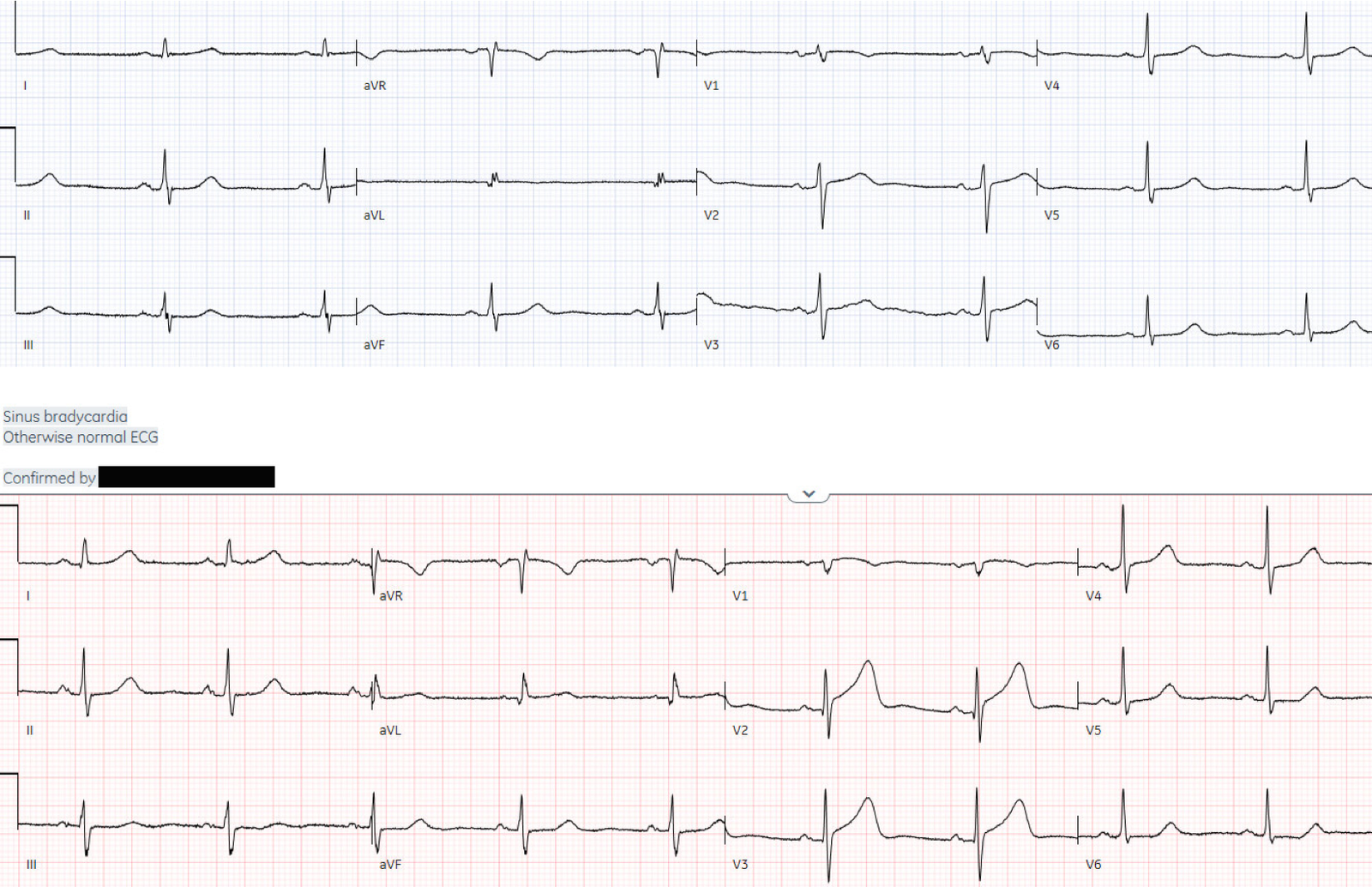

Patient 1: old then new ECG

(Marqette 12SL algorithm)

Patient 2:

(Marqette 12SL algorithm)

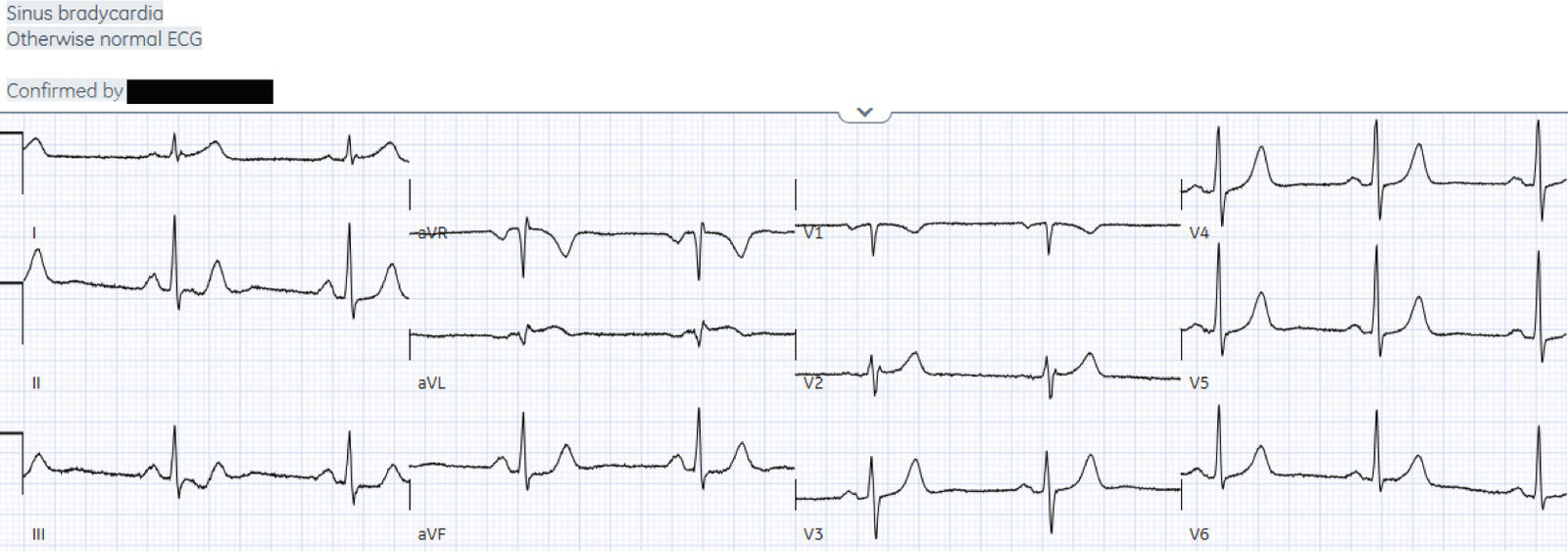

Patient 3: old then new ECG

(Marqette 12SL algorithm labeled ‘normal’, final cardiology ‘inferior injury’))

Patient 4:

(Marqette 12SL algorithm)

ECGs labeled ‘normal’ by

computer interpretation

A

number of small studies have suggested that ECGs labeled ‘normal’ or ‘otherwise

normal’ by computer interpretation are unlikely to have clinical significance,

that it would be safe to avoid interrupting physicians to interpret them, that

any delay to interpretation would not compromise patient care, and that

emergency physicians should not be expected to identify subtle changes that

elude the computer.[1-3] But these studies were very short duration and used

cardiology interpretation of ECGs or emergent angiography rather than patient

outcomes.

Dr.

Smith’s ECG Blog has published a growing list of over

40 cases of ECGs falsely labeled ‘normal’ by the computer which are

diagnostic of Occlusion MI, and Smith et al. have published a number of

warnings about the previous reassuring studies.[4,5]

We

have now formally studied this question: Emergency

department Code STEMI patients with initial electrocardiogram labeled ‘normal’

by computer interpretation: a 7-year retrospective review.[6] Among

394

emergency department Code STEMI patients with acute culprit lesion

requiring

coronary interpretation, 16 (4.1%) presented with an ECG labeled

‘normal’ or

‘otherwise normal’ by computer interpretation. More than a third (37.5%)

were

identified in real-time by the emergency physician, which resulted in

faster

reperfusion times than those which were not identified (mean

door-to-cath time

80.2 vs 237.7 minutes). A majority (62.5%) of those presenting with

‘normal’ ECGs had the cath lab activated without any ECG being labeled

‘STEMI’

by automated interpretation – based on signs of Occlusion MI including

ECG changes,

regional wall motion abnormality on bedside ultrasound, or refractory

ischemia. This is an underestimation of the scale of ‘normal’

ECGs, because we

only looked at patients admitted as Code STEMI, not the greater number

of

patients admitted as ‘non-STEMI’ who are more likely to have subtle

changes

missed by the computer.

The study includes an online supplement of all ‘normal’ ECGs, from which

these 4 examples were drawn. Now let’s review these cases to see the safety of computer interpretation and how these patients were managed. We can also see the potential of the Queen of Hearts (AI trained in identifying OMI) and next steps in training, which also helps our own learning.

Patient 1: anterior OMI

Compared

with baseline (first ECG), the initial ED ECG (second ECG) has mild ST

elevation and hyperacute T waves V2-3 and mild ST depression in V6. This is

diagnostic of LAD occlusion but is equivocal for STEMI criteria and was missed

(and both labeled ‘normal’ by final cardiology interpretation).

A repeat ECG was done 1 hour later:

(Marqette 12SL algorithm)

Further straightening of the anterior ST segment, but was still called ‘normal’ by the automated interpretation and over-reading cardiologist

Ongoing symptoms and an initial troponin of 611 ng/L (normal <16 in females and <26 in males) led to stat cardiology consult and cath lab activation, which

found 100% LAD occlusion. Door-to-cath time was 145 minutes, and peak troponin was >50,000.

See Queen of Hearts AI Bot interpretations below:

Without the benefit of the prior ECG, the Queen of Hearts called the first ECG not OMI but the second one OMI. This shows the importance of prior ECGs (which will be the next phase of training for the Queen), and the subtleties of hyperacute T waves.

Patient 2: high lateral OMI

First

ECG showed mild ST elevation aVL with inferior reciprocal change, diagnostic of

high lateral Occlusion MI. This was identified, leading to immediate patient

assessment including repeat ECG and stat cardiology consult.

(Marqette 12SL algorithm)

No ECG met STEMI

criteria (and both were labeled ‘otherwise normal’ by blinded cardiologist) but

cath lab was activated, which found 99% obtuse marginal occlusion. Door-to-cath

time was 95 minutes, first troponin was 100 and peak 13,280 ng/L.

The Queen of Hearts called both ECGs in isolation as not OMI–the first with mid confidence and the second with high confidence–but is learning over time and will be trained to incorporate serial ECG changes.

Patient 3: inferior OMI

Compared

with baseline (first ECG first), the initial ED ECG (second ECG) has mild

inferior ST elevation and T wave pseudonormalization, reciprocal ST depression

in aVL, ST depression in in V2, and larger T waves in V4-6. This is diagnostic

of infero-posterior Occlusion MI and was immediately identified. Repeat ECG

showed increased inferior ST elevation still not meeting STEMI criteria:

Cath lab was activated and found 100% right coronary artery (RCA) occlusion.

Door-to-cath time was only 52 minutes, and trop rose from 419 to 7875 ng/L.

Without the benefit of the prior ECG, the Queen of Hearts still called the first (and second) ECG as OMI:

Patient 4: posterior OMI

First

ECG had ST depression V2-3 and mild ST elevation in V6, which is diagnostic of

posterior Occlusion MI and was immediately identified. Posterior leads showed

mild posterior ST elevation, labeled ‘nonspecific’ by machine but STEMI on

final interpretation:

Cath lab was activated and found 100% ramus

intermedius occlusion. Door-to-cath time was 91 minutes and troponin rose from

183 to 46,226 ng/L.

The Queen of Hearts identified the first ECG as OMI:

Take home

1.

Don’t

trust the computer interpretation: it can label ECGs diagnostic of OMI as

‘normal’

2.

ECG

signs of OMI can be learned and can help identify subtle occlusions, leading to

rapid reperfusion

3. The Queen of Hearts already is far superior to conventional computer interpretations, and will continue to improve over time including incorporating serial ECGs. This will make expert OMI interpretation widely available, and help us continue to learn the subtleties of ECG interpretation

4.

Other

signs of OMI that complement the ECG include new regional wall motion

abnormalities and refractory ischemia

References

1.

Hughes

KE, Lewis SM, Katz

L, Jones J. Safety of

computer interpretation of normal triage electrocardiograms. Acad

Emerg Med. 2017; 24(1): 120–124

2.

Winter

LJ, Dhillon RK, Pannu

GK, Terrazza P, Holmes JF,

Bing ML. Emergent cardiac

outcomes in patients with normal electrocardiograms in the emergency department.

Am J Emerg Med. 2022; 51:

384–387

3.

Villarroel

NA, Houghton CJ, Mader

SC, Poronsky KE, Deutsch AL,

Mader TJ. A prospective

analysis of time to screen protocol ECGs in adult emergency department triage

patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2021; 46: 23–26

4.

Litell JM,

Meyers HP, Smith SW. Emergency physicians should be shown all triage ECGs, even

those with a computer interpretation of ‘normal’. J Electrocardiol.

2019; 54: 79–81.

5.

Bracey

A, Meyers HP, Smith

SW. Emergency physicians should interpret every

triage ECG, including those with a computer interpretation of ‘normal’. Am

J Emerg Med. 2022; 55: 180–182

6. McLaren JTT, Meyers HP, Smith SW, Chartier LB. Emergency department Code STEMI patients with initial

electrocardiogram labeled “normal” by computer interpretation: A 7-year

retrospective review. Acad Emerg Med

2023 https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.

===================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (10/19/2023):

===================================

Dr. McLaren begins his discussion of today’s post by saying the following:

“A number of small studies have suggested that ECGs labeled ‘normal’ or ‘otherwise normal’ by computer interpretation are unlikely to have clinical significance — that it would be safe to avoid interrupting physicians to interpret them — that any delay to interpretation would not compromise patient care — and that emergency physicians should not be expected to identify subtle changes that elude the computer.”

Dr. McLaren’s review of the ECGs of the 4 patients he presents then conclusively demonstrates the fallacy of accepting a computerized interpretation of “normal” at face value.

I focus my comments on highlighting the erroneous conclusion arrived at in “the number of small studies” that Dr. McLaren alludes to. My Conclusions are identical to those of Dr. McLaren, namely:

- It is not safe to avoid interrupting emergency physicians — simply because prior to the QOH (Queen Of Hearts) AI application — no computer interpretation of “normal” from an ECG of a patient with new or recent CP symptoms could be relied on. Emergency physicians must be interrupted to take a quick look at all ECGs of patients who present with new or recent CP.

- Emergency physicians should (and can!) be expected with training to be able to identify non-stemi OMIs that elude the computer. It is essential that they be able to do so IF they work in an emergency setting.

- With training — it should literally take less than 5 seconds to recognize most of these subtle OMIs that are all-too-often overlooked by the computer.

- The above said — the unfortunate reality (as documented in Dr. McLaren’s excellent discussion) — is that subtle OMIs that can (and should!) be promptly identified, are still overlooked by too many clinicians who continue to deny validity of the new OMI paradigm.

To PROVE My Point:

I had not previously seen the 4 initial ECGs that Dr. McLaren presents in today’s post. “Armed” with the knowledge that each of these patient’s presented to the ED with CP (Chest Pain) — it literally took me less than 5 seconds with each of these ECGs to know that prompt cath was going to be needed.

- Additional details about each of these 4 cases are amply provided in Dr. McLaren’s discussion. But they are not needed to arrive at the quick decision that prompt cath was needed given the initial ECG and the history of new CP.

- I firmly believe that recognition of these KEY findings is a skill that can be taught.

=======================================

Test Yourself! — Take another LOOK at the initial ECG for each of the 4 cases presented above by Dr. McLaren. What are the 1 or 2 KEY findings that should tell you within seconds that in a patient with new or recent CP — that prompt cath will be needed (even before you have looked at the remaining leads)?

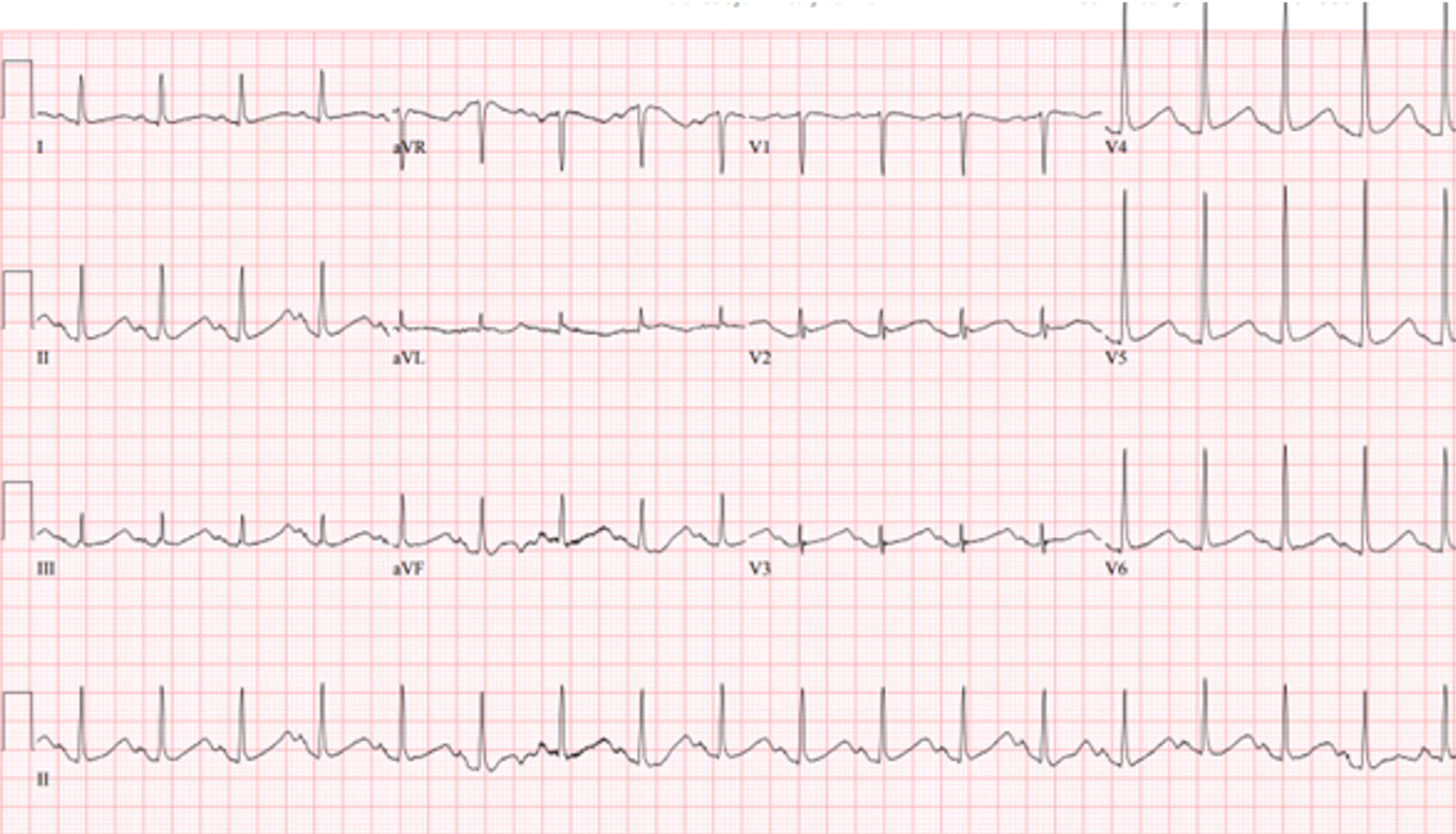

- I reproduce the initial ECG in each of today’s 4 cases in Figure-1.

- I highlight within a RED rectangle the lead (or leads) that immediately capture “my eye” as “No way is this normal for a patient with new or recent CP”.

- I then highlight within a BLUE rectangle the lead (or leads) that I immediately see after identifying the finding in the RED rectangle(s) — which confirm that, “There is no way that this patient with new or recent CP is not going to need prompt cath”.

|

| Figure-1: I’ve reproduced and have labeled the initial ECG in each of the 4 cases in today’s post. (To improve visualization — I’ve digitized the original ECG using PMcardio). |

My RED and BLUE Rectangle Selections:

- ECG #1: In a patient with new or recent CP, the completely disproportionate and overly “bulky” ST-T wave in lead V2 (that surpasses R wave amplitude in this lead) — has to be taken as a hyperacute ST-T wave until proven otherwise (especially given the abnormal q wave in this lead).

- While not as flagrantly abnormal as the ST-T wave in lead V2 — it should be evident that neighboring lead V3 also manifests a hyperacute ST-T wave (that is taller and “fatter”-at-its-peak and wider-at-its-base than it should be, given QRS amplitude in this lead).

- ECG #2: The “ugly-looking” downsloping ST depression, with abrupt angulation that terminates in inappropriately tall, positive T waves in each of the inferior leads — is obviously abnormal.

- Confirmation of acute OMI should be obvious from the abnormal ST elevation in lead aVL (within the BLUE rectangle).

- ECG #3: Normally — there should be slight, gently upsloping ST elevation in anterior leads V2 and V3. As a result, in a patient with new or recent CP — the finding of “shelf-like” straightening with slight ST depression that is maximal in lead V2,V3 or V4 (as seen in Lead V2 within the RED rectangle) — has to be taken as acute posterior OMI until proven otherwise.

- Confirmation of acute posterior (as well as inferior) OMI should be obvious from the disproportionately large Q waves and hyperacute ST elevation in leads III and aVF (within the BLUE rectangle).

- ECG #4: This is a more subtle version of ECG #3 — in that limb lead changes are non-diagnostic. But in a patient with new or recent CP — the “shelf-like” straightening with slight ST depression that is maximal in lead V2 is once again diagnostic of acute posterior OMI (within the RED rectangle).

- The more-subtle-but-still-inappropriate ST segment flattening in neighboring lead V3 confirms acute posterior OMI (within the BLUE rectangle).