A 70-something male with no significant past history presented to a primary care clinic with some progressive SOB over weeks, much worse over last few days. The clinic recorded an ECG which is reported to show atrial flutter with rapid ventricular response. The internal medicine physician prescribed metoprolol and anticoagulation, and discharged him.

As far as I can tell, no ultrasound machine was available.

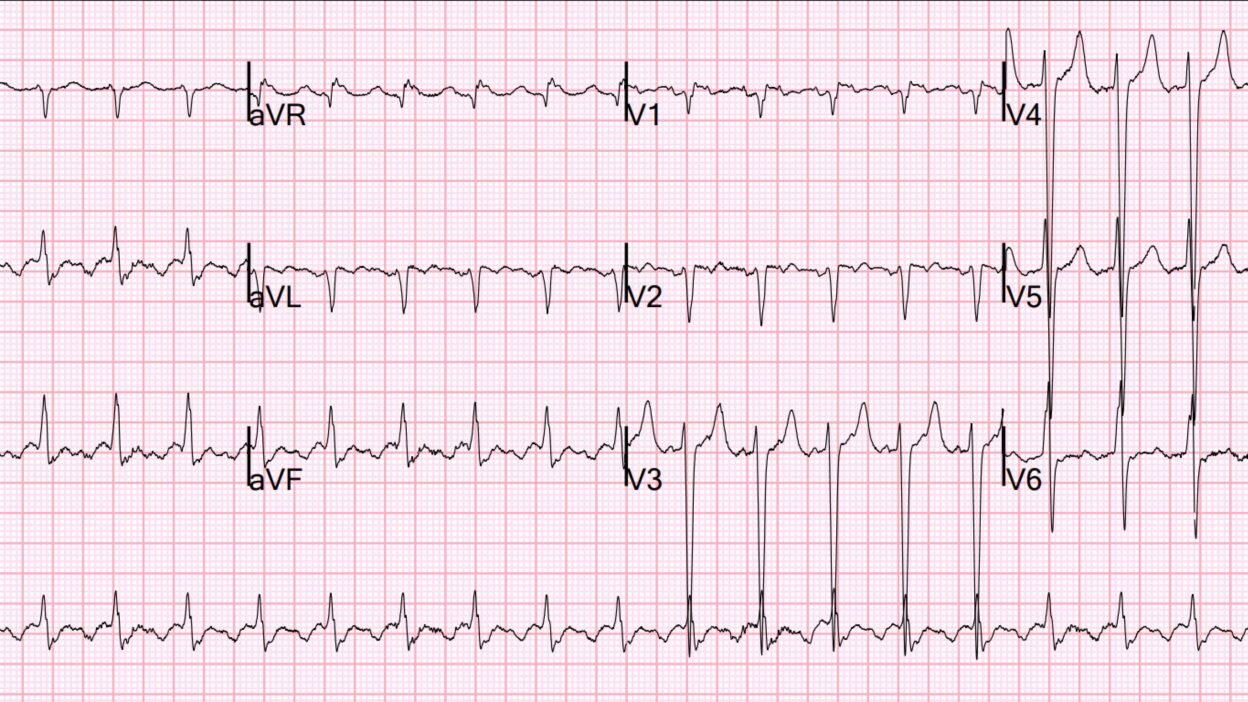

I do not have the ECG they recorded, but when he presented to the ED 2 days later in much worse condition, this was his ECG:

What do you think?

There is clear atrial flutter with a 2:1 conduction with ventricular rate at 126 (so atrial rate is 252, slightly slow for atrial flutter). There is no evidence of acute or old MI. There is a lot of voltage in the precordial S-waves, suggesting LVH, but without the typical LVH repolarization abnormalities.

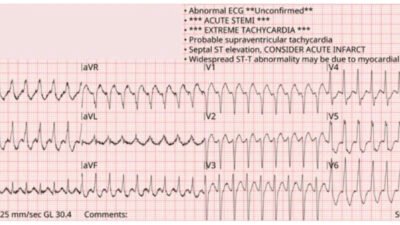

Had the clinic used the PMCardio Queen of Hearts AI app, this is what the result would have been:

She can accurately diagnose low ejection fraction! There is a very high certainty of low EF (0.82 is not a probability of 82%, nor is it sensitivity nor specificity of 82%. It is difficult to correlate that 0.82 with any exact number that we can understand, except to say that it is very highly probable that the patient has an EF less than 40%.)

Had the clinic MD had this PMCardio assessment available, then he would have immediately referred the patient to the ED for new onset heart failure. (New atrial flutter by itself should have led to ED referral). Instead, he treated the patient with metoprolol in order to slow AV conduction. But metoprolol should not be given acutely to patients with new heart failure and low EF (rather, beta blockers are gently titrated up for chronic use in HFrEF after such a patient has been stabilized).

The patient was discharged from the clinic without a diagnosis of low EF or heart failure.

When he arrived in the ED 2 days later, far more short of breath than when he had been in clinic (probably due to the metoprolol), his vital signs were reasonably OK and he was in no distress. But he was clearly clinically in heart failure.

An immediate bedside ultrasound revealed a very large LV with extremely poor LV function (~10%), very large left atrium, and some B lines. BNP was very high (NT-proBNP = 25,000). Troponin was consistent with a chronic cardiomyopathy (hs cTnI ~ 250 ng/L). His lactate was 4.8 mEq/L, and he had mild pulmonary edema.

With elevated lactate and pulmonary edema, this is cardiogenic shock, however mild.

Here is a still image of his bedside ultrasound (sorry I do not have the video):

You can see that the LV is very large and the Left atrium is very large as well. It is likely that the cardiomyopathy came first, leading to elevated LV and LA pressures, LA dilation, and then atrial flutter. I suspect that atrial flutter was probably the final event that tipped him over into heart failure.

Chest Xray showed mild pulmonary edema and a very large heart (cardiothoracic ratio over 50%):

The providers thought that slowing his heart rate might help, so they tried to diminish AV conduction with esmolol. This resulted in hypotension, and so they transferred him to the critical care area where I was working. Fortunately, esmolol has a short half life (which is why they chose it).

This is when we learned from outside charts from the clinic visit from 2 days prior that he had been started on metoprolol for his Atrial flutter but without any evaluation of cardiac function! As stated above, they had also started anticoagulation (but it is important to remember that, if cardioversion were needed, this would not protect from pre-existing thrombus)

Metoprolol is what had worsened his condition and led him to present to the ED, given only because the providers did not recognize LV failure.

It could have been diagnosed with PMCardio AI ECG, preventing a long and difficult hospitalization.

The patient was thinking clearly and was not cool and clammy, and BP at this time was 108/68, so the shock was mild. He was also breathing easily, so the pulmonary edema was mild.

An atrium which is in atrial flutter does not contribute sufficiently to LV filling, not nearly as much as sinus rhythm, so my first objective was to cardiovert. Given the cardiogenic shock, it was worth the risk of stroke. We did not perform TEE to look for thrombus, or even calculate a CHAD(2)DS(2)-VA score, as he needed cardioverson regardless.

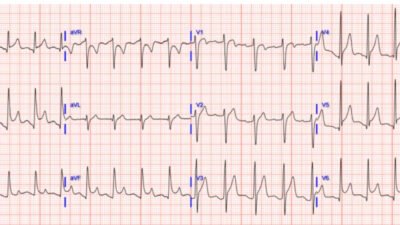

We administered etomidate sedation and cardioverted with 100 J (atrial flutter usually does not need high energy). He converted:

Now he is in sinus rhythm, but, because of metoprolol, and in the context of low stroke volume, the rate is too slow for adequate cardiac output.

Will the ejection fraction output of the PMCardio AI app be the same in sinus rhythm? Yes:

He did improve after cardioversion. We placed central and arterial lines, and started dobutamine. The plan was to add nitroprusside for afterload reduction if the blood pressure remained above 120 systolic.

Magnus Nossen, one of our editors here, comments that patients in this situation (inappropriate bradycardia after cardioversion) can benefit more from temporary atrial pacing than from pressors.

By 4.5 hours after cardioversion, the lactate had dropped from 4.8 to 2.6, then 1.2 by 14 hours.

Further management of cardiogenic shock was continued in the ICU with cardiology supervising.

Later formal echo: Decreased left ventricular systolic performance, severe. The estimated left ventricular ejection fraction is 20-25%.

MRI: The left ventricle is severely enlarged in both size and volume, with

increased myocardial mass consistent with eccentric left ventricular

hypertrophy. End diastolic volume is 366 mL; end systolic is 303 mL. (Thus, stroke volume is 63 mL!). There is severe systolic dysfunction characterized by global hypokinesis with ejection fraction of 17% without regional wall motion abnormalities. (Thus it was a non-ischemic cardiomyopathy — if ischemic, there would be wall motion abnormalities.)

Comment on ejection fraction vs. stroke volume: this shows why someone with chronic cardiomyopathy can function with an EF of 17% whereas a healthy person who suddenly has acute MI with an EF of 17% would be in shock or dead. 17% of 366 mL is 62 mL. 17% of 100mL is 17 mL. It is stroke volume that determines cardiac output, and stroke volume is determined by BOTH EF and end diastolic volume.

Ultimately the patient did well. He was discharged on GDMT (Goal Directed Medical Therapy) for heart failure with reduced ejecion fraction. Entresto, Hydralazine, Bumetanide, Apixaban, Metoprolol, Empaglifozin (SGLT-2) inhibitor, Spironolactone.

Had PMcardio been used at the clinic, low EF (<40%) could have been identified, the patient would not have been discharged, and beta-blockade would have been avoided in favor of urgent ED referral and hemodynamic assessment.

Learning Point:

- A patient in cardiogenic shock with a dysrhythmia benefits from restoration of sinus rhythm, when possible. The small but real risk of stroke in such a case must be tolerated.

- Consider temporary atrial pacing in patients who have sinus bradycardia after cardioversion for atrial flutter or fibrillation, when that bradycardia is due to beta blockade which will eventually wear off.

- The PMCardio AI ECG App can diagnose low ejection fraction with very high accuracy. In a recent presentation at ESC in Madrid, it showed that in a screening population (Framingham cohort!! –no symptoms), the PPV was 33% and NPV 98%. In a patient with symptoms, the PPV would be far higher.

- FINALLY: In Clinics, heart failure is frequently missed. Use the AI app or bedside echo rather than miss it!

= = =

======================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (9/21/2025):

Today’s case addresses the question of which patients with an arrhythmia need to be admitted to the hospital. While fully acknowledging my much easier role of reviewing today’s case from the comfort of my home office large screen desk top computer — I thought it important to revisit some decisions made in today’s case.

Point #1: It is difficult to do quality control based solely on review of the medical chart. Subjective findings can be written by the clinician in a way to “cover” whatever the final discharge diagnosis turned out to be. And in today’s case — We lack objective data (ie, We are not shown the ECG recorded in the primary care clinic at the time today’s patient first presented).

Point #2: The above said — We are told that a previously healthy 70-something man presented with “some progressive shortness of breath“. An ECG was recorded and reported as showing “AFlutter with a rapid ventricular response. A ß-blocker and anticoagulation were prescribed — and the patient was sent home.

- My Impression: From the “retrospectoscope” (ie, sitting comfortably in my office chair) — this patient should not have been sent home. The 1st question to ask is WHY does a previously healthy 70-something man develop new AFlutter with a rapid ventricular response?

- As per the suggested approach by Stiell and Eagles (Clin Exp Emerg Med 11(2):213-217, 2024) — the 1st Priority for assessment of a patient presenting to the ED for new AFlutter is to determine IF the AFlutter is a primary arrhythmia or a secondary arrhythmia due to a medical cause?

- A primary arrhythmia is typically suggested by sudden onset of symptoms (ie, palpitations) — in which case rate or rhythm control without necessarily admission to the hospital may be appropriate options.

- DCCV (Direct Current CardioVersion) has long been established as a safe procedure when performed in the ED by capable emergency physicians for a primary arrhythmia presenting as new-onset AFib or AFlutter within the previous 48 hours (Carpenter and Sargent — BMJ Open Qual 7(4):e000260, 2018).

- In contrast (as per the above cited Stiell and Eagles reference) — new AFlutter with a rapid ventricular response in a patient with progressive shortness of breath, especially in a previously healthy older adult is not the history of a primary arrhythmia, but rather of secondary AFlutter arising in response to some underlying medical disorder such as anemia from GI bleeding, pulmonary embolus, heart failure, etc. In such cases — hospital evaluation of why this patient is now presenting with new AFlutter is essential.

= = =

The 2 ECGs in Today’s CASE:

For clarity in Figure-1 — I’ve reproduced and have labeled the 2 ECGs done on today’s patient. I focus my comment on some interesting findings in these 2 tracings.

Today’s Initial ECG — Realizing that we do not have access to the actual ECG at the time this patient first presented to the primary care clinic — it probably looked similar to ECG #1 obtained 2 days later when this patient presented to the ED.

- As per Dr. Smith — the rhythm is AFlutter with 2:1 AV conduction (Ventricular rate ~130/minute — with flutter rate = 130 X 2 ~260/minute) — and without sign of new or old MI.

- Two additional findings in ECG #1 are: i) LVH (markedly deepened S waves in leads V3,V4,V5 — that easily satisfy Peguero criteria for LVH — Click HERE for my review of LVH Criteria); and, ii) RVH (ie, The presence a narrow rS complex in lead I with predominant negativity in association with marked QRS voltage criteria for LVH indicates RVH until proven otherwise).

- Clinical Impression: Even before turning to the amazing ability of AI for assessing LV function — new AFlutter with a rapid ventricular response in a patient with biventricular hypertrophy should immediately suggest a cardiomyopathy (and with it, the need for sending this 70-something man with “progressive” shortness of breath and this ECG to the hospital for full evaluation).

- PEARL: As per Dr. Smith — the diagnosis in ECG #1 of AFlutter with 2:1 AV conduction is obvious to those of us familiar with the daily interpretation of ED arrhythmias. That said — AFlutter remains the most commonly overlooked arrhythmia (by far in my experience!). To facilitate recognizing this manyfaceted rhythm disturbance, consider the following: i) Remember statistics (ie, that AFlutter is so commonly overlooked) — therefore, if you have a regular SVT rhythm at ~130-170/minute but without clear sign of sinus P waves (ie, no clear upright P wave in lead II) — then Think AFlutter until proven otherwise! — ii) Look at my “Go-To Leads” for picking up subtle atrial activity (highlighted in RED in ECG #1 = leads II,III,aVF; lead aVR; and lead V1). If you focus on one or more of these leads in an SVT at ~130-170/minute, but without sinus P waves — You’ll often see 2:1 activity of AFlutter (highlighted in ECG #1 by slanted RED lines). Extra Credit: You can then prove 2:1 AFlutter in less than 5 seconds by pulling out your calipers to verify precise 2:1 activity of the deflections I highlight with slanted RED lines.

= = =

Today’s Repeat ECG — Following synchronized cardioversion of this patient’s AFlutter — a much more stable and slower supraventricular rhythm was restored ( = ECG #2, as shown below in Figure-1).

- Technically — the rhythm in this repeat ECG is not “sinus”. Instead, as highlighted by the colored arrow P waves in Figure-1 — there are multiple P wave morphologies.

- I suspect the RED arrow P waves are the 2 sinus P waves in ECG #2 — because these are the clearly upright P wave forms in this tracing. The rather tall, peaked appearance of these P waves in the inferior leads (ie, for beats #2 and #5) — suggests RAA, consistent with this patient’s dilated cardiomyopathy.

- The beat-to-beat variability in P wave morphology that we note for the first 5 beats in ECG #2 suggests a variant (slower) form of a multifocal atrial rhythm — which is commonly seen in patients with an underlying cardiopulmonary disorder.

- P wave morphology for the last 6 beats in the long lead II rhythm strip of ECG #2 finally stabilizes. Technically, this is not reestablishment of a “sinus” rhythm — because each of these last 6 P waves manifests a small-but-present initial negative deflection, which tells us these P waves do not originate from the SA node. Instead — this ectopic atrial focus begins just before beat #6 (Beat #6 is actually a junctional escape beat — since it’s PR interval is too short to conduct).

- To Emphasize: Clinical implications of the rhythm in ECG #2 are for practical purposes, the same as if a sinus rhythm would have been the result of cardioversion. Therefore, this post-cardioversion rhythm is actually an excellent response to cardioversion of this patient’s AFlutter — and I strongly suspect that true sinus rhythm will return as this patient’s underlying acute heart failure continues to improve.

Figure-1: I’ve reproduced and labeled the 2 ECGs from today’s case.

= = =