This was sent by an old friend, who was working with a physician assistant student, Lily McLean. She had just that minute downloaded the Queen of Hearts, and this case made her an OMI convert.

They were at a hospital without PCI capability.

Lily and my friend came on for the morning shift and were told this by the departing emergency physician: “60-something woman presented at time zero with left chest heaviness beginning 3.5 hours prior when she was up and about at home. It built steadily to 8 or 9/10. No radiation or SOB, mild nausea.”

“No known CAD, smoker, controlled HTN, moderate obesity. I gave ASA, ordered serial trops. I was planning for a GI cocktail in this ‘low risk patient.’ ‘There were no EKG findings.‘ The computer noted Q-waves with possible old MI.”

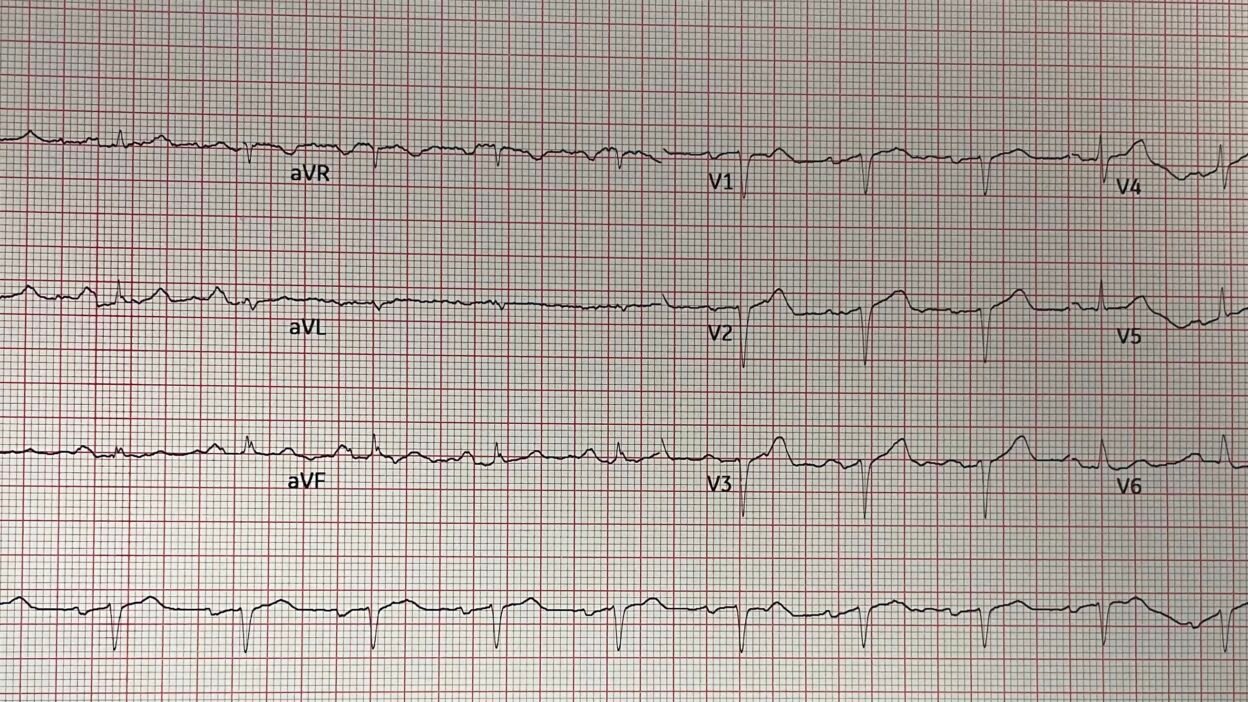

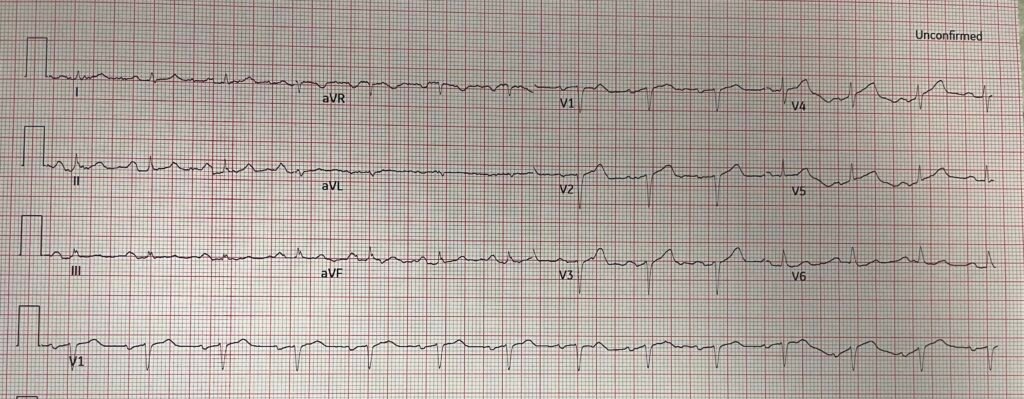

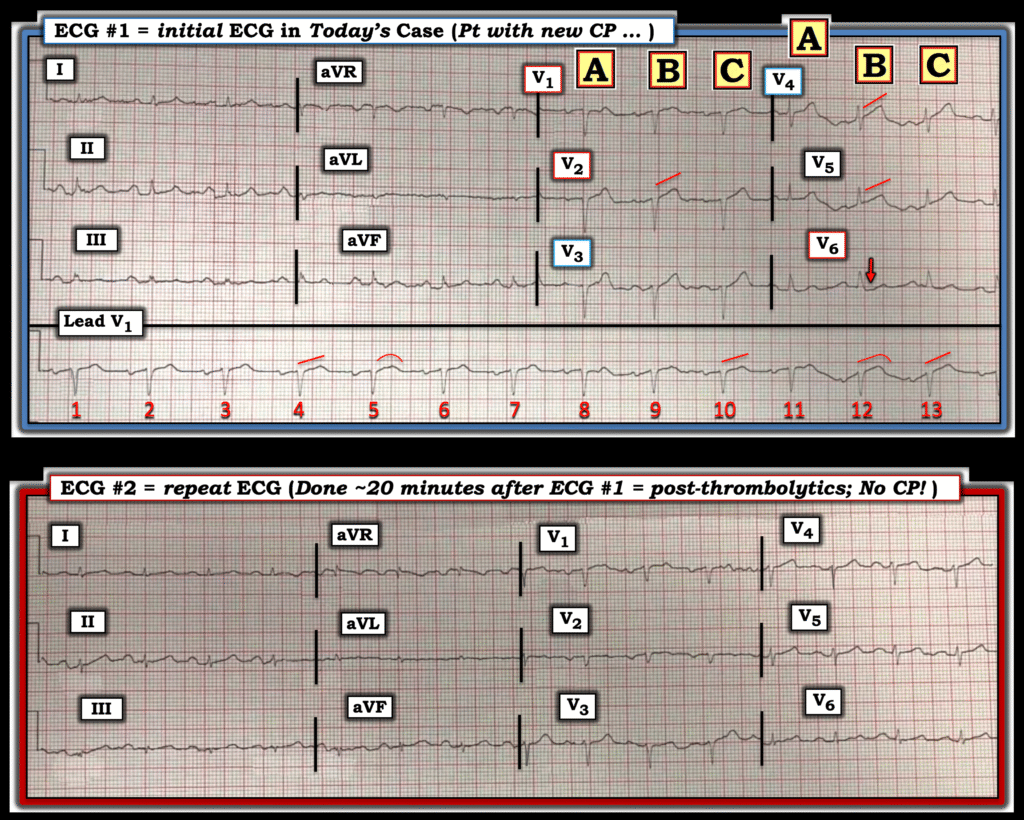

Here is that ECG:

What do you think?

I showed this to an interventional cardiologist with 30 years of experience, and he said “Old anterior MI.”

Smith: But it is diagnostic of Acute LAD OMI. There is a QS-wave in V2, and 0.5 mm STE in leads V2,3, and 5, and 1 mm in V4. There are hyperacute T-waves in V2-5. [This is an NSTEMI with occlusion (NSTEMI-OMI)].

My friend did not like the EKG and the patient was still describing 3/10 pain. My friend was literally explaining the EKG concerns while Lily loaded PMCardio Queen of Hearts onto her phone. At the same time, the initial troponin came back at 0.314 ng/mL.

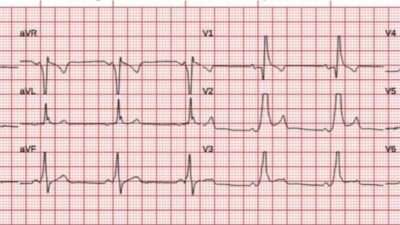

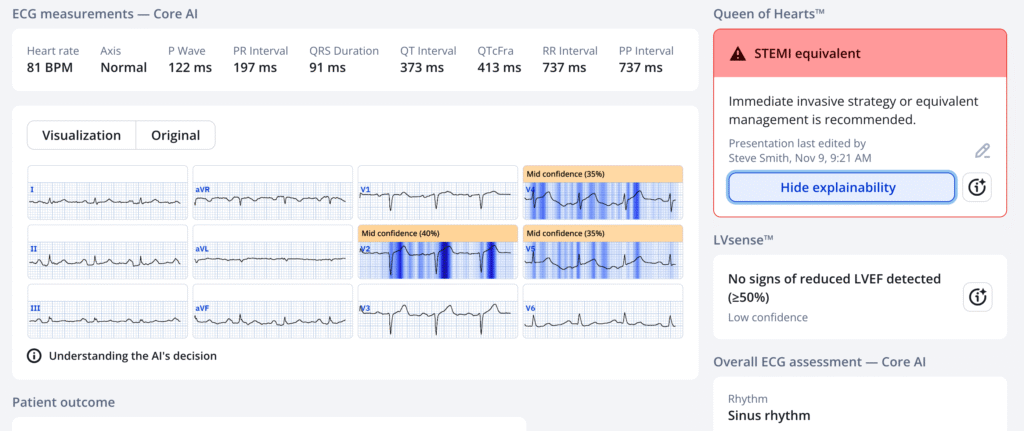

Here is the Queen’s interpretation:

PMcardio for Individuals now includes the latest Queen of Hearts model, AI explainability (blue heatmaps), and %LV Ejection Fraction. Download now for iOS or Android: https://individuals.pmcardio.com/app/promo?code=DRSMITH20. As a member of our community, you can use the code DRSMITH20 to get an exclusive 20% off your first year of the annual subscription. Disclaimer: PMcardio is CE-certified for marketing in the European Union and the United Kingdom. PMcardio technology has not yet been cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical use in the USA.

My friend assessed her thromboytic risk and she had no contraindications. So he gave thrombolytics.

Comment: there are those who believe that the only patients who are eligible for thrombolytic therapy are those who meet the STEMI millimeter criteria. This is hogwash. In order to refute it, I would need to write a whole paper here, but there is NOTHING to support limiting thrombolytics only to those who meet the criteria. If the artery is occluded or nearly so, and you can’t get the patient to PCI fast enough, then lytics are indicated if the risk is not too high. One must always remember that about 1% of patients receiving thrombolytics will have an intracranial bleed. See the NEJM article at the bottom.

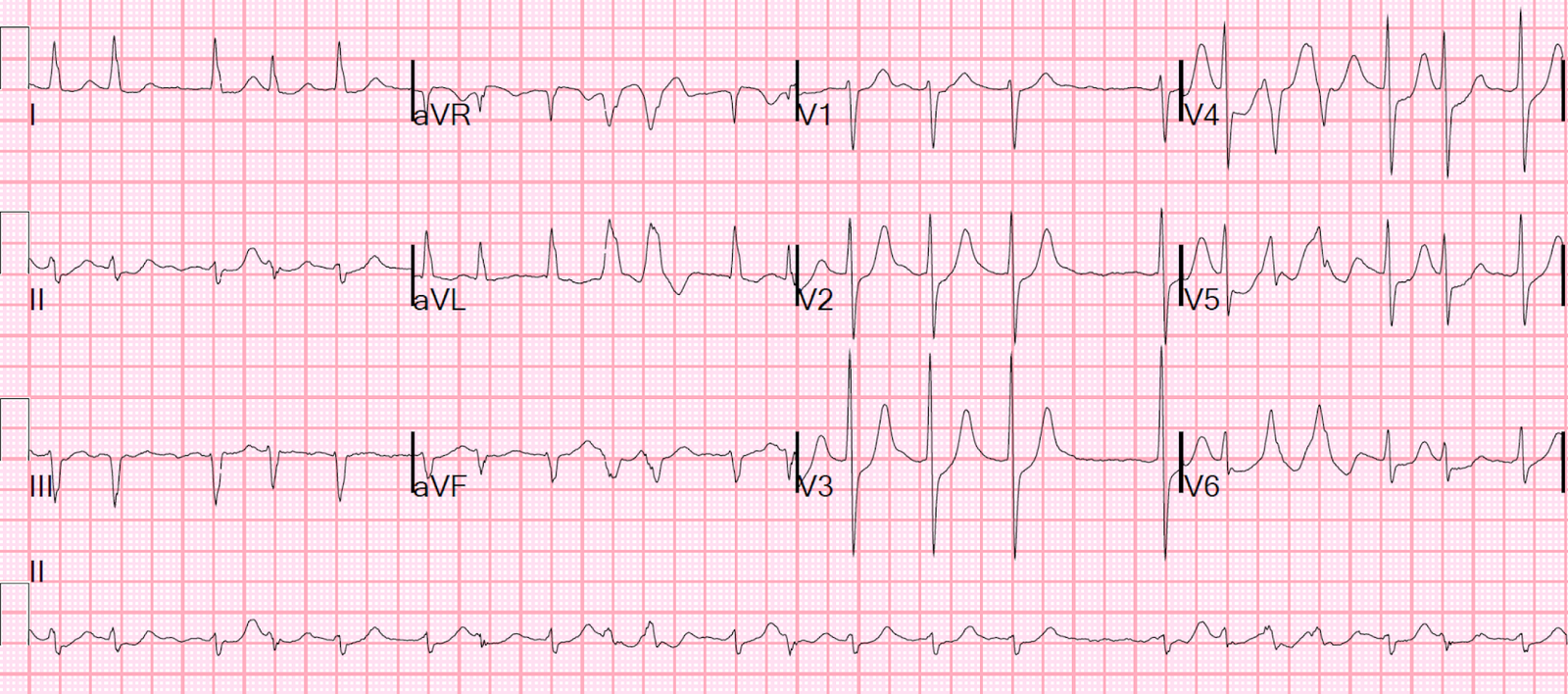

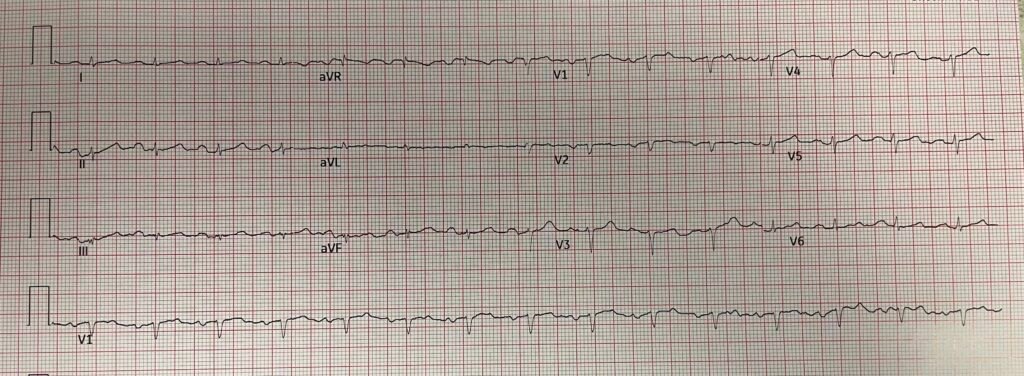

Case continued: Her pain completely resolved rapidly, and we obtained another ECG 20 minutes later:

All STE and HATW are resolved. BOTH pain free AND ECG resolution: reperfusion.

My friend writes about the confusion of many cardiologists surrounding the issue of OMI (STEMI Equivalents):

“I called to the PCI receiving center and told the nursing supervisor I had given lytics to a patient who needed to be transferred for emergent cath. She said – “oh you mean a STEMI?” And I said “no, an OMI,” and tried to explain. I ultimately gave up – she was hung up on their “STEMI” protocol and was flummoxed when I said just treat it as a STEMI because I had told her there was no STE. She got the interventionalist. I described the EKG and told him it represented a STEMI equivalent and had given lytics and the troponin result.”

And continues: “He said he would not cath her until tomorrow due to bleeding risk post lytics. Then he tried to tell me there was no need to worry, that she could not have ongoing cardiac damage in the absence of STE. I told him I disagreed. Then since he wasn’t taking her right to the cath lab the supervisor said I would have to wait until they had an ICU bed open up before they would accept the patient. So much downstream stuff gets messed up clinging to this STEMI model. Thank goodness the cardiologist at least opined they needed to accept her right away as an ED to ED transfer.”

“The cardiologist did not want this patient to get lytics. They probably seldom see this since typically they go right to cath there and probably haven’t seen rural docs giving lytics in the absence of typical STE. I told him lytics is the only thing I can do to help this patient who is at least 3 hours from PCI. They just don’t get the big picture and approach this in a very simplistic automatic and self-serving brainless manner.”

Outcome: Since the patient had reperfused, and remained pain free without any further ECG evidence of ischemia, angiography was appropriately delayed until the next day, when it showed at culprit with 80% residual stenosis, but the LAD was only 2 mm, too small for PCI. She went for CABG. No echo or troponin data, nor subsequent ECGs, were available.

When to give thrombolytics if you are not at a PCI center:

- If first medical contact (medics arrive at patient’s home) to PCI time (at PCI center) will be > 120 minutes, and it is definitely acute OMI, give thrombolytics, then transfer.

- If time from Door (at small hospital) to Balloon (at PCI center) is > 90 minutes, give thrombolytics, then transfer.

- Door-in, Door-out time should not exceed 30 minutes.

- Only about 25% of transfers obtain a first medical contact to PCI time of < 120 minutes, so in most cases thrombolytics should be given.

- Thrombolytics work best when early after onset of chest pain and, more importantly, with high ECG Acuteness.

- Here is a short summary of high acuteness, from that post: Hyperacute T-waves indicate a large amount of viable, salvagable, myocardium. Q-waves indicate lower acuteness, but may be present early in anterior MI; thus, in anterior MI, T-waves are more important. Inverted T-waves signify either low acuteness or an open artery.

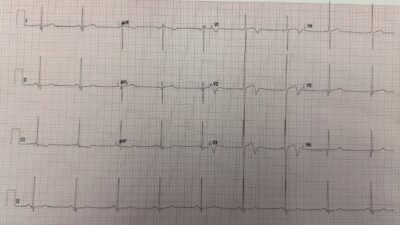

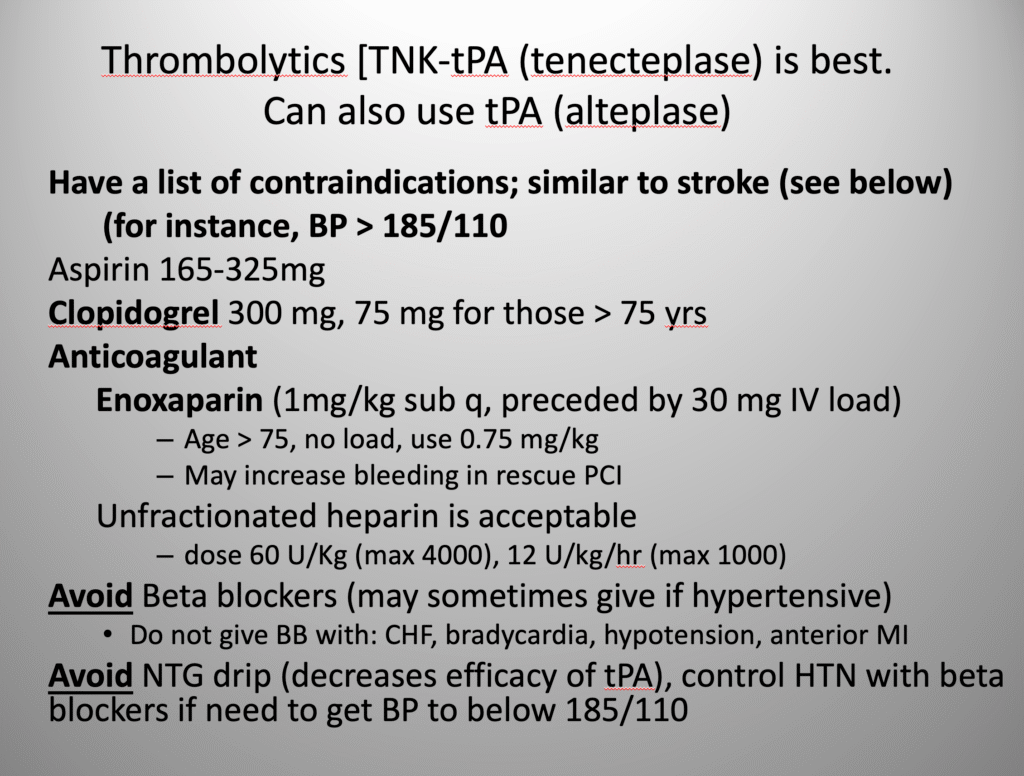

This is the recommended protocol for Thrombolytics:

When do patients need to get immediate PCI after thrombolytics, and when should they wait:

Patients who do not have reperfusion after thrombolytics, as indicated by ECG resolution and resolution of pain, should go immediately to the cath lab after arrival at the referral insitution. In patients with diagnostic ST Elevation, evidence of reperfusion in at least 70% resolution of ST elevation. For patients who only have HATW, reperfusion has not been carefully defined. In this case, the HATW were clearly resolved.

This is called “Rescue PCI.”

For high-risk ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients who received thrombolytics, the ACC/AHA guidelines recommend early PCI (within 2 to 6 hours) for patients with a high-risk indicator, such as persistent ST-segment elevation, chest pain, or hemodynamic instability.

However, routine PCI immediately after thrombolysis in asymptomatic patients is not beneficial. For low risk patients who reperfuse with thrombolytics, one should wait to do PCI: “The guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) state that immediate routine PCI after successful thrombolysis in a ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is not beneficial and can be harmful. Instead, rescue PCI (for failed thrombolysis) is recommended, and an early elective PCI within 2 to 24 hours is suggested for many patients who were initially treated successfully with thrombolytics. A primary PCI approach is preferred if a patient can be brought to a PCI-capable hospital within 90 minutes of first medical contact.

Here is the article establishing Rescue PCI from NEJM 2005: Rescue Angioplasty after Failed Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction

Here is the most relevant article, the TRANSFER-AMI study by Cantor et al. in the New England Journal. Routine Early Angioplasty after Fibrinolysis

for Acute Myocardial Infarction

= = =

======================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (11/21/2025):

Cases like the one presented today are frustrating — when we know what optimal care is, but despite our best efforts — explaining the premise of the OMI Paradigm is simply not possible to colleagues who deny OMI existence (ie, Denial of the clinical reality that many acute coronary occlusions simply do not produce ST elevation sufficient to qualify as a “STEMI” — or even if they eventually do, it is often not until much later in the course that ST segments finally elevate).

= = =

The Initial ECG:

For clarity and ease of comparison in Figure-1 — I’ve put together today’s initial ECG and the repeat ECG done ~20 minutes after beginning thrombolytics, by which time this patient’s CP (Chest Pain) had already essentially resolved.

- Although subtle — the initial ECG in Figure-1 is definitely not “without EKG findings”. Instead (as per Dr. Smith and the QOH interpretation) — chest lead hyperacute T waves are present that are diagnostic of acute LAD occlusion until proven otherwise.

= = =

I wil add the following thoughts about ECG #1:

- There is low voltage in both limb leads (ie, ≤ 5 mm in all 6 limb leads) and chest leads (ie, ≤ 10 mm in all 6 chest leads). In a patient being evaluated for new CP — this is relevant, as low voltage may indicate cardiac “stunning” from an ongoing large infarction (Click HERE — for more on clinical implications of low voltage).

- There is significant artifact, especially in the chest leads — with resultant marked variation in ST-T wave morphology. This is problematic — because of the difficulty it imposes on determining which QRS complexes in the chest leads represent “true” ST-T wave morphology.

- For example, in a patient with new CP — complexes “B” and “C” in lead V1 immediately caught my “eye” because these ST segments are coved and slightly (but disproportionately) elevated with respect to the very small S wave in this lead. This ST-T wave abnormality is not seen in complex “A”, which is artifactually distorted. So I looked next in the long lead V1 rythm strip below the 12-lead ECG — which provides 13 “looks” at lead V1 ST-T wave morphology. I’ve drawn in RED the 5 ST-T waves in the long lead V1 that are clearly abnormal ( = the ST segments in the long lead V1 for beats #4,5; 10; 12,13) — whereas the other 8 ST-T waves in this long lead V1 did not look nearly as abnormal to me.

- KEY Point: The reason assessment of the ST-T wave in lead V1 was important to me in my interpretation — is that once I know in a patient with new CP that 1 or 2 leads are definitely abnormal — it becomes far more likely that lesser ST-T wave abnormalities in neighboring leads are “real” and indicative of an acute evolving event.

- I’ve highlighted with RED lines those chest lead ST-T waves (for complex “B” in leads V2,V4,V5) in which ST segment straightening and disproportionately “bulky” T waves are clearly present. I was less confident that complex “A” in each of the 6 chest leads is abnormal.

- Finally — complex “B” (but not “A” and “C”) in lead V6 seems to suggest ST flattening with slight depression (RED arrow) — which if real, could be consistent with Precordial Swirl given the appearance of ST-T waves in “B” and “C” in the other chest leads.

BOTTOM Line: When the critical decision of how strongly to argue with OMI “non-believers” and whether or not to use thrombolytics when STEMI criteria are not met — We want to obtain as technically good of a tracing as possible, to optimize the validity of our interpretation.

- That said — even with the above-described artifact-induced variations in ST-T wave morphology in ECG #1 — this initial ECG looks like an acute LAD occlusion in progress.

- But if in doubt — then immediately repeat the ECG.

= = =

Figure-1: Comparison between the initial ECG — and the repeat ECG recorded ~20 minutes later after starting thrombolytics (at which point the patient was now pain-free! ).

= = =

The Repeat ECG:

Artifact distortion is less (albeit not completely gone) in ECG #2. That said — lead-to-lead comparison of ST-T wave morphology clearly shows marked improvement, with definite deflation of the overly “bulky” ST-T waves in virtually all of the chest leads.

- Together with simultaneous complete relief of CP within 20 minutes of beginning thrombolytic therapy — this degree of improvement seen in the repeat ECG proves that despite not satisfying STEMI criteria — the initial ECG was the result of acute LAD occlusion.

- P.S.: If anything — QRS voltage is less in the repeat ECG. I’m intellectually curious if this dramatic low voltage is the result of cardiac stunning, that fortunately was mitigated by prompt initiation of thrombolytic therapy. It would be interesting to see if a tincture of time will result in a good clinical outcome (in association with ultimate return of normal QRS amplitudes).

- BOTTOM Line: The conviction to administer thrombolytic therapy for this STEMI-/OMI+ case was potentially life-saving.

= = =