Answer: Almost Never

2 cases

Case 1: This was sent to me by a reader whose partner managed the case:

This was a 55 yo female non-smoker with a history of HTN. No CAD. She presented with 3 hours of fluctuating cycles of SOB that would worsen over 15 minutes then improve partly, associated with Nausea. There was No chest or back pain. Note: 1/3 of STEMI do not have chest pain.

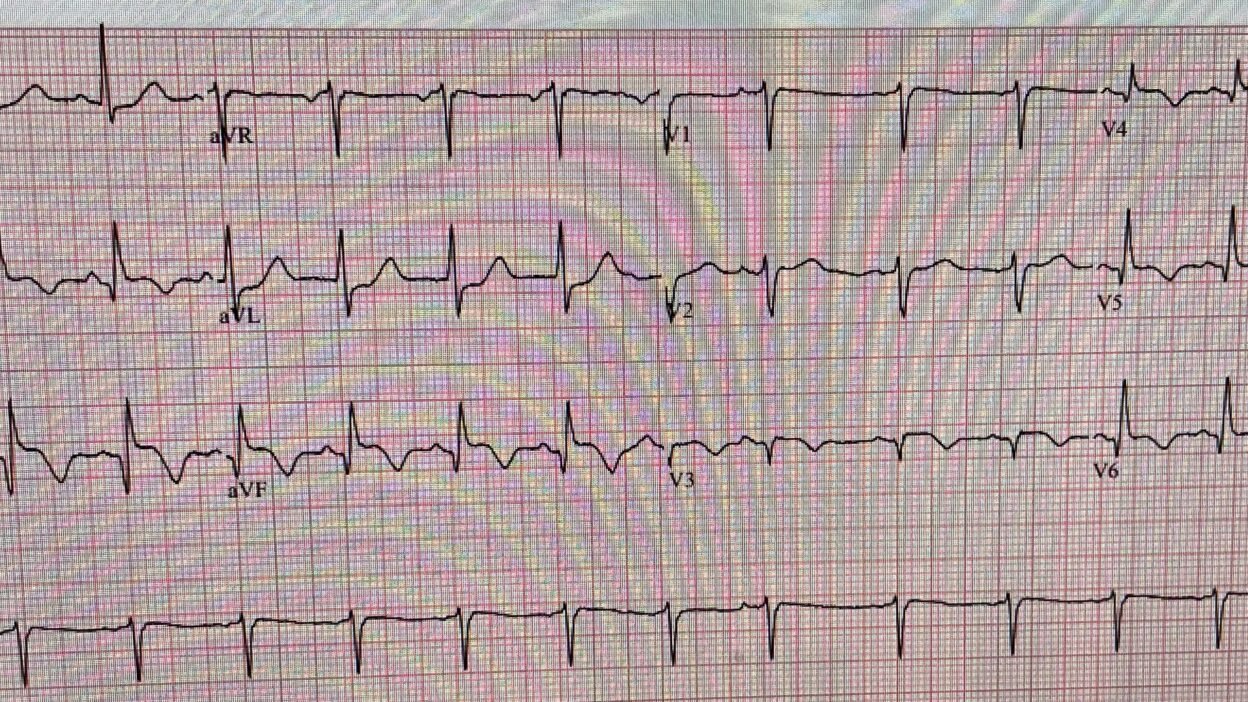

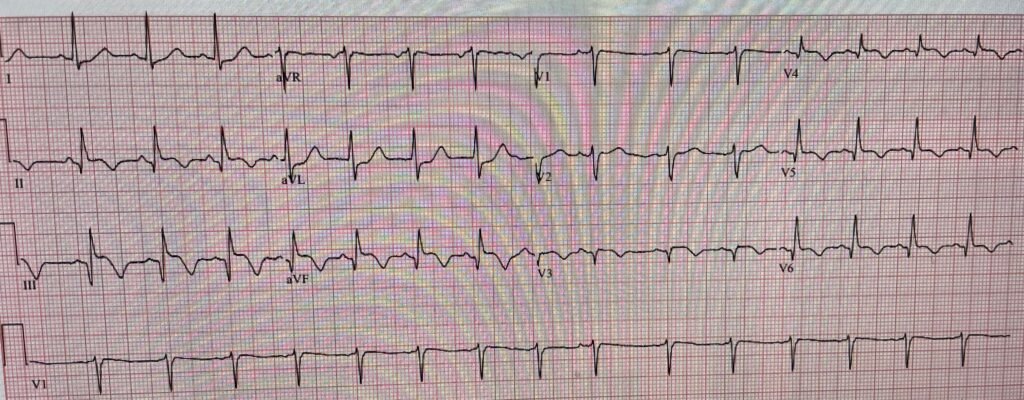

Here is the presenting ECG:

This is clearly inferior and lateral OMI, though really it appears as if it is 1) subacute, with well-formed Q-waves in inferior and in lateral leads V3-V6, and 2) probably reperfused, with inverted “reperfusion” T-waves in inferior leads and V3-6. Even if the ECG suggests subacute OMI, reperfused OMI, or both, the presence of active symptoms (whether chest pain, SOB, or other) mandate emergent cath lab activation.

Aside: This may be a fully reperfused subacute OMI which never had chest pain (was truly a silent MI) but over time, due to decreased contractility or to valvular dysfunction developed heart failure/pulmonary edema as a result of the infarct. In other words, presence of symptoms might be due to the consequences of infarction rather than the presence of active coronary thrombosis.

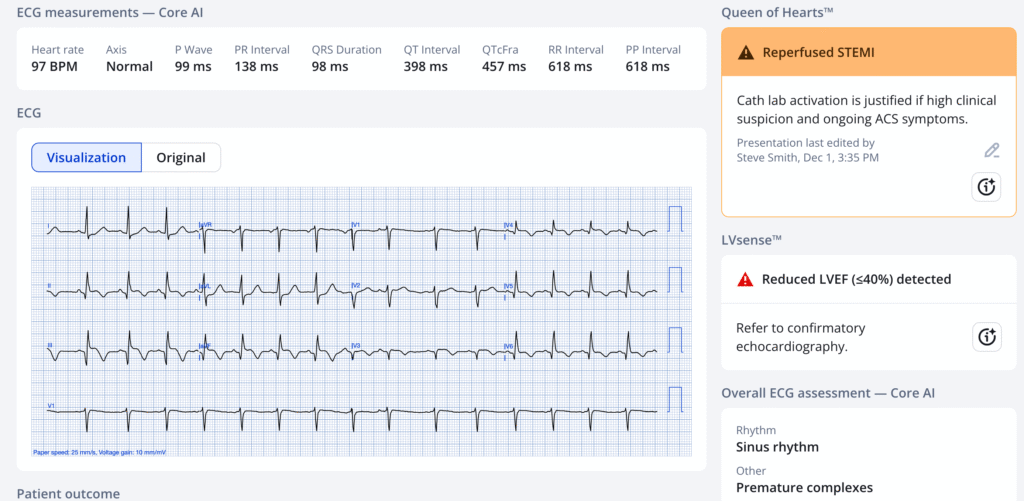

The Queen of Hearts agrees with Reperfusion:

The physician (who is at a non-PCI hospital) recognized that the EKG shows OMI (“STEMI subtype”). He sent it to his consulting cardiologist at a PCI center and that cardiologist appropriately recommended thrombolytics and transfer ASAP for PCI.

The patient remained short of breath and systolic BP was 80 mmHg, so low dose norepinephrine was started. He decided to order “screening CXR” prior to thrombolytics. This portable chest X-ray was shot:

What do you think?

There is evidence of pulmonary congestion. There APPEARS to be a wide mediastinum, but the image is ROTATED! The trachea should be directly between the clavicular heads, but the left clavicular head is rotated to the right and the right clavicular head is far over to the right. This results in the anterior part of the aortic arch being positioned far to the right of where it should be and fools you into thinking there is a wide mediastinum. There is no widened mediastinum.

The treating physicians thought that the mediastinum was not normal, and therefore he worried that his acute MI was due to aortic dissection. So he sent the patient for a chest CTA before giving thrombolytics.

It was a difficult study with partial dye extravasation.

The patient had a cardiac arrest in the CT scanner immediately after image acquisition. It was reported as a nonshockable rhythm.

Interestingly the physician spoke to cardiology during 50 minutes of CPR and was told to give lytics if he achieved ROSC, but only if CTA ruled out dissection.

–Initial troponin I = 3.12 ng/mL (confirms subacute OMI)

–NT-Pro-BNP > 30,000 pg/mL (very high, along with chest x-ray, it confirms that pulmonary congestion is the etiology of the SOB.

The patient was in heart failure due to subacute OMI.

CT Angiogram report: suboptimal contrast, no dissection, ground glass lungs, cardiomegaly, distended hepatic veins and IVC.

She was not resuscitated.

In the chart, it says that “due to aortic dissection on the differential, TNK-tPA could not be safely administered.”

By trying to rule out aortic dissection, when this is entirely unnecessary, the patient died in the CT scanner of her Occlusion MI.

Case 2

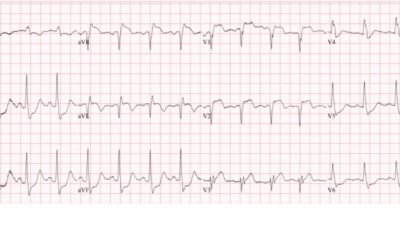

Case 2 has already published on this blog: A very elderly woman with sudden severe chest pain radiating to her back

In this case, I had very high suspicion of dissection because of back pain and differential blood pressures. There was a large anterior OMI on the ECG. The patient was very elderly. I realized that IF this acute anterior OMI was due to aortic dissection, then there was nothing that could be done to save her. So I simply assumed it was a vessel thrombosis and treated as such. A bedside ultrasound showed what looked like a flap, then she suddenly had dissection into the pericardium and then free rupture into the chest, all documented on ultrasound.

Discussion

Acute OMI as a result of acute aortic dissection is rare. The best study is this one, in which 0.5% of acute STEMI were due to aortic dissection. Of 1576 acute STEMI, 8 had aortic dissection. 5 per 1000 STEMI. Rare.

Zhu Q-Y, Tai S, Tang L, et al. STEMI could be the primary presentation of acute aortic dissection. Am J Emerg Med [Internet] 2017;35(11):1713–7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2017.05.010

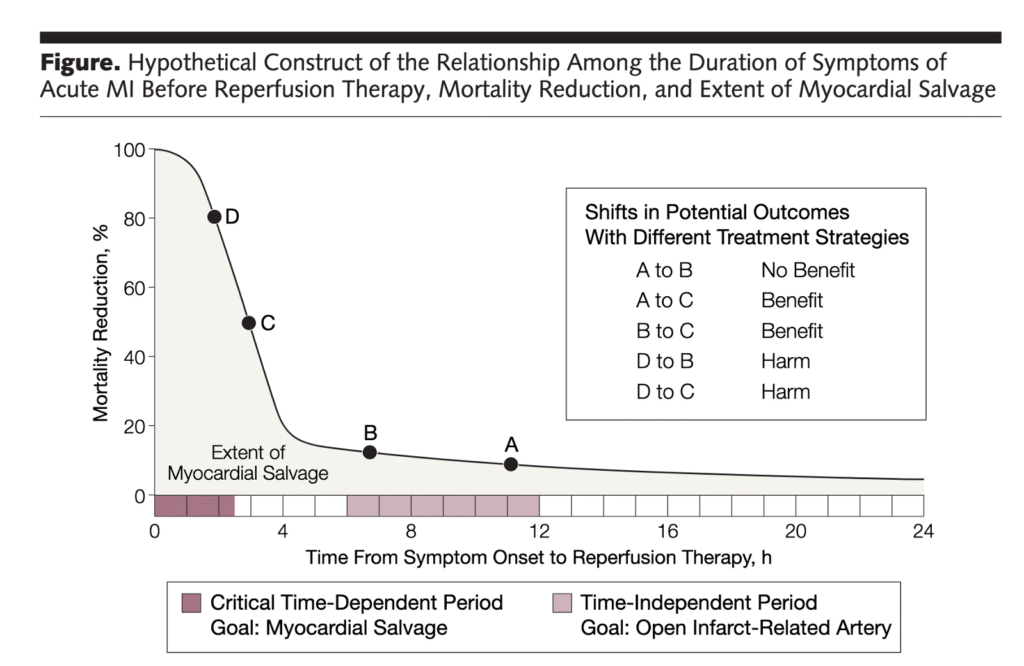

Remember that ANY delay to reperfusion of Occlusiom MI sacrifices myocardium!!

By 4 hours after chest pain onset, 80% of the mortality benefit of thromboylitics is gone!

Gersh BJ, Stone GW, White HD, Holmes DR Jr. Pharmacological facilitation of primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: is the slope of the curve the shape of the future? JAMA [Internet] 2005;293(8):979–86. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15728169

In this case, because the OMI was subacute, at which point thrombolytics have much less benefit (but still some up to 12 hours), the delay is probably not what killed her.

What killed her was having a cardiac arrest far from the resuscitation area. The CT scanner is a very bad place to have an arrest.

Learning Point

Overthinking

The case contributor wrote that he thinks his partner was overthinking:

“Overthinking in my experience as a medical director was very difficult to address once a physician has finished training. It can often become an engrained approach even, or especially, in smart, thorough, and well-intentioned physicians. These tend to be risk averse doctors, with a ready rationale for their decision-making and they are often defensive when things turn out poorly. I have tried and mostly failed to help them overcome this. For these physicians, no amount of thinking can be too much and the more of it they do the better they think they are and the more cavalier the rest of us appear to them. There are other specialties better suited to this approach. In emergency medicine we should be like Goldilocks – think just the right amount, be prepared to quickly choose the right bed, and lie in it.”

One definition of overthinking: a negative thought pattern where you get stuck analyzing thoughts, situations, or decisions excessively, replaying them over and over without finding a resolution. This can involve dwelling on past mistakes and worrying about worst-case scenarios.

My summary of Overthinking: “Just because you can think of other etiologies of the patient’s critical illness does not mean that those etiologies are remotely likely.”

As for STEMI/OMI in due to Aortic Dissection: If you have any worry about aortic dissection, do a bedside ultrasound and ONLY do a CT if:

1) the clinical presentation is suggestive of aortic dissection and the ultrasound is supportive of AD, or

2) the Ultrasound is diagnostic of AD

Screening for aortic dissection with bedside cardiac ultrasound is quite sensitive and specific. If there are no findings of AD on bedside ultrasound, it should be extremely rare for a STEMI (OMI) patient to undergo a CT scan before reperfusion therapy.

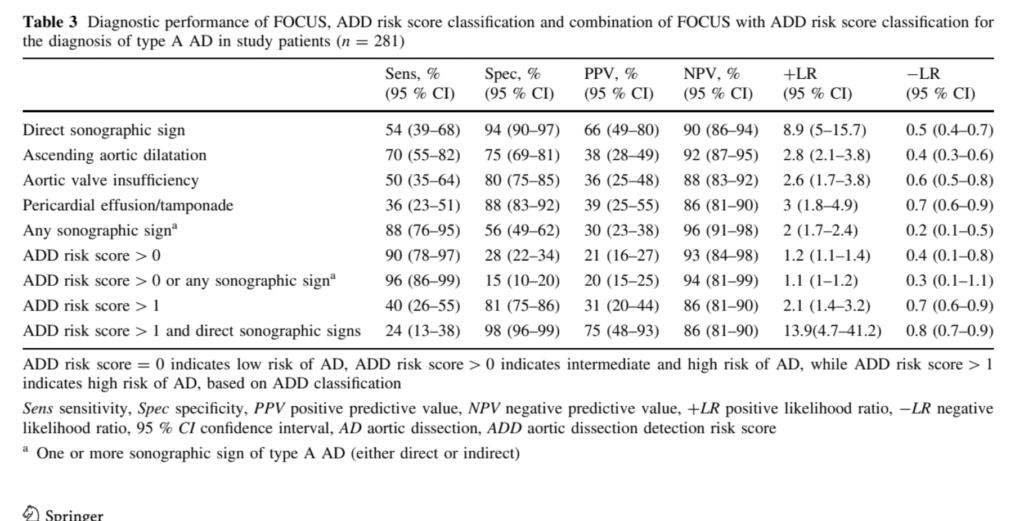

These high sensitivities and specificities are among patients who do not already have a diagnosis of acute OMI. Among patients for whom you already have a diagnosis of OMI for their symptoms, the diagnostic utility of a negative test rules out the diagnosis of AD. See Bayesian analysis below.

Table of Sono findings of AD from Nazerian et al.:

Here is a Bayesian Guide to Aortic Dissection, by my friend Jose Nunes de Alencar.

Let’s look at these cases using Likelihood Ratios.

1. The “Rule Out” Power

This is where the true value of bedside ultrasound lies in this scenario.

- Pre-test Probability: 0.5% (Pre-test Odds approx 0.005).

- The Test: Absence of any sonographic sign.

- Likelihood Ratio (-LR): 0.2.

- Calculation: 0.005 x 0.2 = 0.001 (Post-test odds).

- Result: The risk drops from 0.5% (1 in 200) to 0.1% (1 in 1000).The risk is now negligible, effectively ruling out dissection for the purpose of emergency management. It gives you the green light to skip the CT and save the myocardium.

2. The “Rule In” Power

- The Test: Presence of a direct sonographic sign (flap).

- Likelihood Ratio (+LR): ~9.0.

- Calculation: 0.005 x 9.0 = 0.045.

- Result: The risk rises from 0.5% to 4.5%.Although a 4.5% post-test probability seems “low,” look at the relative increase: the risk has increased nearly 10-fold. Therefore, even with a low absolute post-test probability, this probability would be higher enough to pause and at least consider a CT scan.

3. The “Synergistic” Scenario (Clinical suspicion + Positive Echo)

Here is where the “patient as an individual” concept changes everything. If the patient presents with specific symptoms (e.g., tearing pain, pulse deficit), they are no longer in the 0.5% baseline group.

- Pre-test Probability: Let’s conservatively estimate it at 20% (Pre-test Odds 0.25).

- The Test: ADD risk score > 1 AND direct sonographic signs.

- Likelihood Ratio (+LR): 13.9.

- Calculation: 0.25 x 13.9 = 3.47 (Post-test odds).

- Result: The probability rise from 20% to ~78%.

In this specific subset, the ultrasound is not just a “pause” button; it effectively becomes diagnostic. The post-test probability is so high that we are shifting gears entirely from “OMI suspicion” to “Aortic Dissection management” (calling the surgeon, controlling BP, and getting a CT to confirm and plan the repair, not just to rule it out).

References

- Nazerian, Peiman, et al. “Diagnostic performance of emergency transthoracic focus cardiac ultrasound in suspected acute type A aortic dissection.” Internal and emergency medicine 9.6 (2014): 665-670.

- This study was performed in a group of 281 patients suspected of AD (not all chest pain patients and not all STEMI patients), of whom 50 (18%) had AD.

- Detection of any FOCUS sign (direct or indirect) of AD had a sensitivity of 88% (95% CI 76–95 %) for the diagnosis of type A AD. Presence of ADD risk score >0 or detection of any FOCUS sign increased diagnostic sensitivity to 96% (95 % CI 86–99 %). Detection of direct FOCUS signs had a specificity of 94% (95% CI 90–97 %), while combination of ADD risk score [1 with detection of direct FOCUS signs had a specificity of 98 % (95 % CI 96–99 %).

- Pare, Joseph R., et al. “Emergency physician focused cardiac ultrasound improves diagnosis of ascending aortic dissection.” The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 34.3 (2016): 486-492.

- Results: Of 386547 ED visits, targeted review of 123 medical records and 194 autopsy reports identified 32 patients for inclusion. Sixteen patients received EP FOCUS and 16 did not. Median time to diagnosis in the EP FOCUS group was 80 (interquartile range [IQR], 46-157) minutes vs 226 (IQR, 109-1449) minutes in the non-EP FOCUS group (P=0.023). Misdiagnosis was 0% (0/16) in the EP FOCUS group vs 43.8% (7/16) in the non–EP FOCUS group (P=0.028). Mortality, adjusted for do-not-resuscitate status, for EP FOCUS vs non–EP FOCUS was 15.4% vs 37.5% (P=0.24). Median rooming time to disposition was 134 (IQR, 101-195) minutes for EP FOCUS vs 205 (IQR,

114-342) minutes for non–EP FOCUS (P= 0.27). Conclusions:

Patients who receive EP FOCUS are diagnosed faster and misdiagnosed less compared with patients

who do not receive EP FOCUS

- Results: Of 386547 ED visits, targeted review of 123 medical records and 194 autopsy reports identified 32 patients for inclusion. Sixteen patients received EP FOCUS and 16 did not. Median time to diagnosis in the EP FOCUS group was 80 (interquartile range [IQR], 46-157) minutes vs 226 (IQR, 109-1449) minutes in the non-EP FOCUS group (P=0.023). Misdiagnosis was 0% (0/16) in the EP FOCUS group vs 43.8% (7/16) in the non–EP FOCUS group (P=0.028). Mortality, adjusted for do-not-resuscitate status, for EP FOCUS vs non–EP FOCUS was 15.4% vs 37.5% (P=0.24). Median rooming time to disposition was 134 (IQR, 101-195) minutes for EP FOCUS vs 205 (IQR,

= = =

======================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (12/11/2025):

Today’s discussion by Dr. Smith features 2 difficult cases for which optimal management requires more than just ECG interpretation. It especially features the need to balance the pros and cons of various management strategies — with the clinical likelihood of potential risk vs potential benefit interventions. The PEARLS put forth in Dr. Smith’s above discussion are worthy of repetition:

- Portable chest x-rays on “sick” patients are often suboptimal in quality. Overlooking this clinical reality in the above rotated and underexpanded AP CxR — led providers in Case #1 to falsely conclude there was mediastinal widening. (It could also mislead as to whether or not there is heart failure/pulmonary edema).

- Acute OMI as a result of acute aortic dissection is rare ( = the rare 0.5% incidence of acute aortic dissection among a study group of 1,500+ patients with an acute STEMI, in whom the STEMI was caused by acute aortic dissection — citation by Zhu et al above by Dr. Smith).

- The decision to look for this 0.5% of STEMI patients whose STEMI is due to acute aortic dissection is not benign — because the clinical reality is that doing so will significantly delay thrombolytics/PCI in the 99.5% of STEMI patients who do not have aortic dissection (as per Dr. Smith’s Figure showing 80% of mortality benefit from thrombolytics is lost by 4 hours after CP onset).

- Spending a moment to check BP symmetry in both extremities (as done by Dr. Smith in Case #2) — is far quicker than having to do chest CTA.

- If truly concerned about possible aortic dissection — Use bedside cardiac ultrasound to screen for this! ( = Doing bedside U/S is far quicker than chest CTA).

= = =

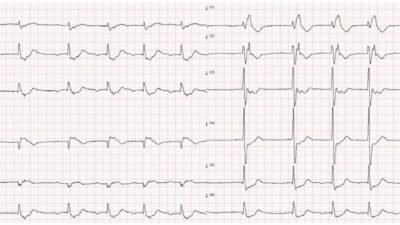

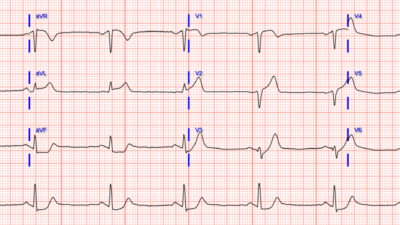

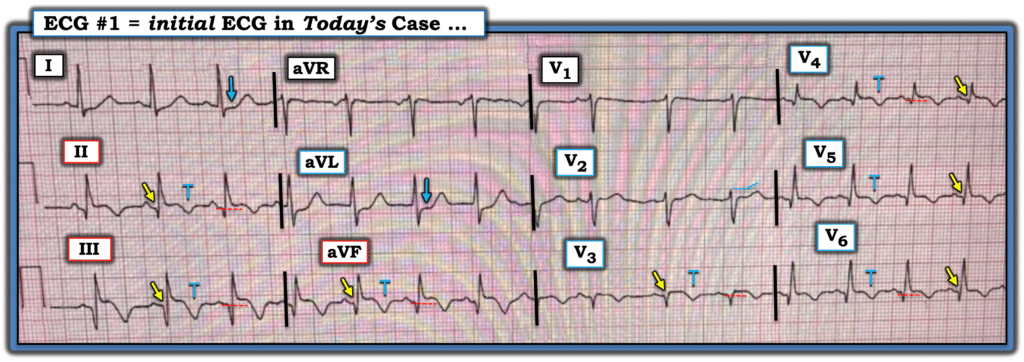

Relevant to the above PEARLS are details in the initial ECG from Case #1:

- The rhythm is sinus tachycardia (rate = 100/minute), with a PAC seen in simultaneously-recorded leads V1,2,3. Most acute MIs are not associated with tachycardia unless “something else” is going on (ie, heart failure, impending cardiogenic shock or other acute medical problem).

- There is evidence of an extensive STEMI in Figure-1 (ie, YELLOW arrows highlighting Q waves in leads II,III,aVF; and in V4,V5,V6 — with loss of r wave from V2-to-V3 leading to a QS in lead V3).

- In addition — there is still ST elevation in 6 leads (RED dotted lines) — in association with deep T wave inversion in 7 leads (the BLUE “T’s”) — which as per Dr. Smith, together with the terminal T wave positivity in leads I,aVL — suggest ongoing reperfusion.

- The ST segment flattening in lead V2 in the absence of at least slight upsloping ST elevation in this lead (especially given that neighboring lead V3 shows coved ST elevation! ) — suggests posterior OMI.

- In summary — I interpreted ECG #1 as indicative of an extensive infero-postero-lateral STEMI — most probably subabcute (as per Dr. Smith) given the above-noted ECG signs of ongoing reperfusion. I thought acute (or recent) occlusion of a dominant LCx vessel might account for this ECG picture.

- Alternatively, given the impossibility of determining from a single tracing what is “new” vs “recent” superimposed on top of “old” — I thought it likely that this patient may well have significant underlying multi-vessel disease with an unpredictable collateralization pattern resulting in anterior injury ( = the QS with coved ST elevation in lead V3 — with Q waves and ST elevation in the remaining chest leads).

- Regardless — The patient in Case #1 has clearly suffered an extensive recent MI — now with clear ECG signs of ongoing reperfusion plus tachycardia suggesting the possibility of associated heart failure, if not impending shock. Correlating these ECG findings to the time sequence of this patient’s presentation — I suspect that IF this patient’s extensive MI had been caused by acute aortic dissection — that fatal cardiac arrest would have occurred long before this point in time (therefore further reducing the already low likelihood that the extensive STEMI in Case #1 was the result of acute aortic dissection).

= = =

Figure-1: I’ve reproduced and labeled the initial ECG from Case #1.

= = =

= = =