A man in his 30s presented for similar symptoms (acute substernal chest pain) twice, each visit one year apart.

Visit #1

History including acute substernal chest pain, shortness of breath, and diaphoresis, within 3 hours onset. Obesity but no other cardiac risk factors. Vitals within normal limits.

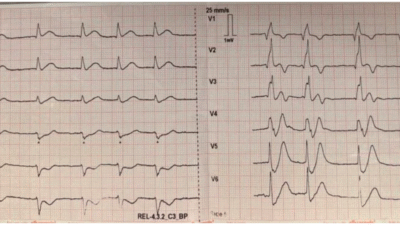

ECG:

What do you think?

Meyers: Many leads with STE, meeting STEMI criteria, but T waves are non-hyperacute, benign ST morphology, spodick sign, and some PR depression. DDX is pericarditis vs. normal variant. No signs of OMI. Notice how aVR must mathematically have ST depression because many leftward/downward leads have STE.

Smith: I think most important is that the STE in II is far higher than in III AND there is no reciprocal STD in aVL. Our study showed that zero patients with pericarditis had reciprocal STD in any lead other than aVR, AND that 99% of inferior OMI had some (often minimal) amount of STD in aVL. So although I often write that “you diagnose pericarditis at your peril”, in this case it is almost certainly not OMI.

Bischof JE, Worrall C, Thompson P, Marti D, Smith SW. ST depression in lead aVL differentiates inferior ST-elevation myocardial infarction from pericarditis. Am J Emerg Med [Internet] 2016;34(2):149–54. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2015.09.035Queen of Hearts interpretation:

New PMcardio for Individuals App 3.0 now includes the latest Queen of Hearts model and AI explainability (blue heatmaps)! Download now for iOS or Android. https://www.powerfulmedical.com/pmcardio-individuals/

Code STEMI activated, emergent angiogram: normal coronary arteries

Serial high sensitivity troponin I:

<6, 13, 15, 19, 14, (none further measured)

ESR elevated at 30 mm/hr, CRP elevated at 6.1 mg/dL

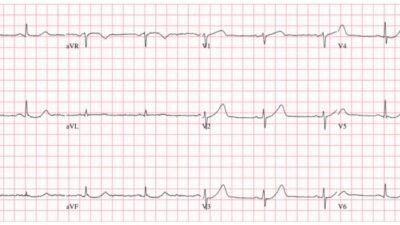

Repeat ECG:

Queen of Hearts interpretation:

In this view you can see the raw score (from zero to 1.0, with zero being highest possible certainty of NO OMI, and 1.0 being highest possible certainty of YES OMI). This ECG has a score of 0.00, as confident as possible that there are no ECG signs of OMI, despite lots of STE and obvious STEMI criteria.

Echo with no wall motion abnormalities, normal EF, and no pericardial effusion.

Cardiac MRI showed:

- No late gadolinium enhancement of the myocardium to suggest infarction or inflammation

- Normal LVEF

- “Patchy pericardial late enhancement adjacent to LV free wall with abnormal T1 and T2 signal that is consistent with acute pericarditis”

Visit #2

Almost exactly the same history written in the HPI as visit 1 above.

ECG:

Queen of Hearts:

Code STEMI activated, emergent angiogram: normal coronary arteries

Serial high sensitivity troponin I: <6, <6, <6; (none further measured)

ESR elevated at 33 mm/hr, CRP elevated 8.7 mg/dL

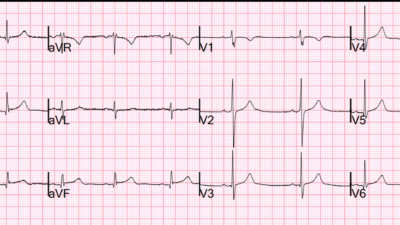

Repeat ECG:

Queen of Hearts:

Echo: no wall motion abnormalities and normal EF. A moderate sized pericardial effusion was present.

Cardiac MRI during this visit showed:

- No late gadolinium enhancement of the myocardium to suggest infarction or inflammation

- Normal LVEF

- “Moderate sized circumferential pericardial effusion measuring up to 1.8 cm inferior to the right ventricle and 1.2 cm lateral to the left ventricle. The effusion is transudative with T1 times in the 3100-3200 ms range. There are no signs of increased intrapericardial pressures. There is pericardial late gadolinium enhancement adjacent to the basal to mid anterior wall and anterior to the apex consistent with inflammation/acute pericarditis.”

ECG 4 days later:

Queen of Hearts:

The patient was treated well for recurrent pericarditis.

Learning Points:

This was a case of pericarditis, not OMI. Pericarditis does exist, but it’s much rarer than OMI. Please don’t ever misdiagnose OMI for pericarditis. The harm of one missed OMI outweighs many unnecessary uncomplicated angiograms.

Anyone can become an ECG expert with guided practice and correlation with actual patient outcomes (not just the final diagnosis written in the STEMI metrics database!). We have provided this education on this blog since 2008 for free, and always will continue to do so.

If you don’t have the time or desire to become an expert to provide optimal care for these patients and OMI patients, then consider using an AI ECG model that is trained for this purpose. Queen of Hearts is made by us, and is by far the best so far. If someday competition arises and performs better, then that would be even better for patients!

Smith: I have been teaching the ECG diagnosis of MI for 37 years. After all that experience, I believe that very few health care providers have all of the characteristics necessary to be true ECG experts. This expertise can be learned to some extent by some people, but for most even with dedicated study it is not reachable. Such a learner requires:

1. Motivation

2. Time

3. The (rare) native visual talent for “seeing” waveform differences and similarities.

Therefore, I believe that the PMCardio Queen of Hearts AI Model is an absolute necessity for good care of chest pain patients.

Example: At TCT in San Francisco at the end of October, we will present a study of over 1000 STEMI Activations and show that the use of the Queen of Hearts on the initial ECG would have 1) decreased false positive activations from 41% to 7% and 2) resulted in earlier activation for 2/3 of the 30% who were not activated on the first ECG.

= = =

======================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (9/28/2025):

Today’s case by Dr. Meyers highlights a number of important points regarding the diagnosis and potential misdiagnosis of acute pericarditis as a cause of new CP (Chest Pain) in patients who present for emergency care.

- The 1st problem in this regard relates to the challenge of assessing the true incidence of acute pericarditis (ie, of pericarditis without associated myocarditis) in an emergency setting. Cited as accounting for ~5% of all ED admissions for acute CP (Andreis et al — Intern Emerg Med 16(3):551-558, 2021 — and — Dababneh and Siddique — StatPearls, 2025) — our experience suggests the true incidence of acute pericarditis accounts for a significantly lower percentage than this of ED admissions.

- Instead, as we frequently caution on Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog — the entity of acute pericarditis tends to be greatly overdiagnosed (all-too-often seemingly by default through application of a series of imperfect ECG criteria). As a result, when confronted with a case suggestive of acute pericarditis — I find myself repeating the mantra instilled in me by the wisdom of Drs. Meyers and Smith, “In a patient with new CP — You diagnosis acute pericarditis at your peril” (simply because in an emergency setting — an acute cardiac syndrome will be statistically much more common than acute pericarditis).

- The above said — today’s case illustrates that pure acute pericarditis does occur on occasion.

- PEARL: The fact that today’s patient presented 1 year after his first episode of acute pericarditis with a nearly identical clinical history — should have been a big clue that his 2nd presentation represented a recurrence of acute pericarditis. Up to 30% of patients with an initial episode of acute idiopathic pericarditis will have ≥1 additional episodes ( = recurrent pericarditis).

- NOTE: The entity of acute myocarditis (including acute myo-pericarditis) is not nearly as elusive a diagnosis as is pure acute pericarditis — because unlike pure pericarditis, serum Troponin is generally elevated (often significantly) with myocarditis. As we’ve shown in many cases in Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog — at times, cardiac catheterization may be needed to distinguish between acute OMI vs acute myocarditis.

= = =

Today’s Initial ECG:

Armed with awareness that acute OMI is a much more common cause of acute CP presenting to the ED than acute pericarditis — I found myself thinking that of all the initial ECGs I’ve seen in my decade of following all cases on Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog — today’s initial ECG (that I’ve reproduced and labeled in Figure-1) fits a “textbook description” for the ECG picture of acute pericarditis as well as any other ECG that I’ve seen.

- I review “My Take” on the ECG diagnosis of acute pericarditis in My Comment in the May 16, 2023 post of Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog (including a 9-page PDF summary).

- For additional insight regarding ECG diagnosis of acute pericarditis in a challenging case — Check out My Comment in the June 15, 2025 Post .

ECG Findings in Figure-1 that suggest Acute Pericarditis:

- Diffuse ST elevation (seen here in 9/12 leads! = RED arrows ).

- PR depression in multiple leads — with PR elevation in aVR (BLUE arrows in these leads).

- The ST-T wave appearance in lead II resembles lead I (more than it does lead III — whereas with acute OMI, lead II resembles lead III).

- Unlike acute MI — with acute pericarditis: i) There is no reciprocal ST depression; ii) Infarction Q waves are absent (The q waves that are seen in Figure-1 are small in size and narrow — consistent with normal “septal” q waves); iii) There is normal R wave progression (whereas with anterior MI there is often loss of anterior R waves); and, iv) The shape of the elevated ST-T waves is upsloping (“smiley”-configuration) — as opposed to the ST segment coving that is more often seen with acute OMI.

- The ST/T wave ratio in lead V6 >0.25 (or at least it looks like the ratio is >0.25 — with this being somewhat difficult to assess given PR depression seen in lead V6).

- Spodick’s Sign is present (a downsloping of the TP [or entire QRS-TP] segment that may be present in a number of leads with acute pericarditis = the downward slanting RED dotted line in lead V5).

= = =

Figure-1: I’ve labeled the initial ECG in today’s case.

Additional Clinical Considerations:

I’ll highlight some selected clinical points of interest regarding the diagnosis of acute pericarditis (supported by the Andreis and Dababneh/Siddique manuscripts that I cite above):

- Potential etiologies of acute pericarditis are numerous (including bacterial, viral, fungal infections — malignancy — connective tissue disorders — metabolic conditions (uremia; myxedema) — pericardial trauma; — post-MI (Dressler Syndrome) — infiltrative disorders (amyloidosis; sarcoidosis — and others).

- The above said — in up to 90% of cases, no clear etiology for acute pericarditis is found — in which case the disorder is classified as acute “idiopathic“ pericarditis.

- Because of how common it is with acute idiopathic pericarditis for no definite etiology to be found — extensive diagnostic evaluation is rarely necessary unless there is suspicion for a specific etiology.

- Potential treatments for acute pericarditis include: i) NSAIDs; ii) Colchicine (for its anti-inflammatory effect); iii) Corticosteroids; and, iv) Other anti-inflammtory agents (with newer treatments including anti-interleukin-1 [IL-1] agents that hold promise for more effective control of recurrent pericarditis — Kumar et al — ACC: Latest in Card, 2023).

- As alluded to earlier — the overall incidence of recurrent idiopathic pericarditis cited in the literature is between 15-30% of cases. Of note — treatment of patients with corticosteroids expedites resolution of symptoms, but is associated with a much higher recurrence rate. In contrast — use of colchicine instead of corticosteroids is associated with a much lower recurrence rate (with colchicine often combined with NSAIDs, and with treatment often extended for 6-12 months). The hope is that newer anti-interleukin-1 agents will be even more effective in preventing recurrence.

- NOTE #1: No mention is made in today’s history as to whether a pericardial friction rub was (or was not) present. This is unfortunate (but all-too-common in the cases I routinely see posted on the internet) — because IF a pericardial friction rub is heard, then you have made the diagnosis of acute pericarditis! (and unnecessary cardiac catheterization may have been avoided in both instances in which today’s patient presented with acute pericarditis).

- NOTE #2: No mention was made regarding any potential positional relationship or pleuritic nature of this patient’s CP (the CP was instead described as “substernal”, associated with shortness of breath and diaphoresis). While a patient’s description of the nature of their CP is by definition subjective (with imperfect correlation to textbook description of pericardial pain) — there is a tendency for pericarditis CP to be “pleuritic” (increasing with inspiration due to commonly associated pleural inflammation) — and “positional” (commonly relieved by sitting up and exacerbated by lying supine, which increases “stretch” on the inflammed pericardium).