This case was sent by Eric Funk of the Expert Witness Newsletter

https://expertwitness.substack.com/p/death-after-ed-visit-for-covid

A 21-year-old college student went to the ED for cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath. He was known to have COVID.

Temperature was 36.3, Pulse 84, Resp 16, BP 134/86 and SpO2 = 97%. He was “well appearing.”

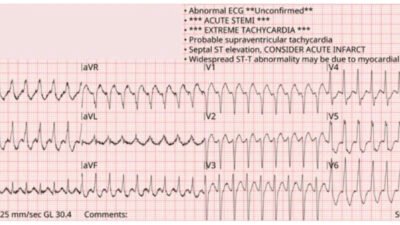

An EKG was recorded:

What do you think?

This ECG was sent to our “EKG Nerdz” group without any clinical information, and all of us said “Pulmonary Embolism”. It is diagnostic of PE. “Domed” ST Elevation, T-wave inversion in V1-V3 AND in lead III.

This post tells you why and compares the T-wave inversion of Wellens’ syndrome to that of PE: A crashing patient with an abnormal ECG that you must recognize

Another good post with links to many PE Cases:

Below, lots of info:

- On D Dimer, including in Covid

- Which is more sensitive for PE, Dimer or CT?

- Dyspnea and viral infections

- Why don’t we have electrocardiologists?

Case Continued:

CXR negative. ECG interpretation was interpreted as “nonspecific T-waves” ( suspect that this is a confirmation of the conventional computer interpretation).

The long note basically says that there is no serious illness going on.

The patient was discharged.

Comment: Even if you miss this ECG, you should not miss the diagnosis. No one with shortness of breath should be discharged without an explanatory diagnosis. Viral infection is NOT an explanation for dyspnea. Viral infections cause dyspnea if they cause pneumonia or bronchospasm. If you think it is bronchospasm, you need to at least confirm that with peak flow, then albuterol nebulization, then peak flow. The patient should have a peak flow below predicted value and, after albuterol, the patient’s dyspnea should resolve and the peak flow improved. If all of this does not happen, then you have NOT explained the dyspnea and the patient needs a workup for pulmonary embolism or heart failure, or maybe a pneumonia that is only visible on CT scan or with ultrasound. Moreover, you should ultrasound the heart.

D dimer is underutililized in diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. And D dimer remains useful in patients with Covid.

Question for you: What is more sensitive for pulmonary embolism, CT pulmonary angiogram or D Dimer (at cutoff of 500 ng/mL)?

Answer: Dimer.

Source: Open Evidence: https://www.openevidence.com/ask/73627608-e6d8-4232-88e3-c8796d87f5b8

“D-dimer is more sensitive than computed tomography (CT) for detecting pulmonary embolism (PE). Meta-analyses and systematic reviews demonstrate that high-sensitivity D-dimer assays have a pooled sensitivity of approximately 97% (95% CI, 96–98%), while CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) has a pooled sensitivity of about 94% (95% CI, 0.89–0.97) for PE detection.[1-2] This means D-dimer is less likely to miss cases of PE, but it is much less specific than CT, leading to more false positives and necessitating confirmatory imaging in many cases.”

“The American College of Physicians, in its clinical guidelines, recommends D-dimer as an initial test to rule out PE in patients with low or intermediate pretest probability, due to its high sensitivity.[3] CT is reserved for patients with a positive D-dimer or high clinical suspicion, as it is highly specific and can confirm the diagnosis and identify alternative causes of symptoms”.[2]

“In summary, D-dimer is more sensitive than computed tomography for detecting pulmonary embolism, but CT is more specific and is required for definitive diagnosis”.[1-3]

In summary: expert ECG interpretation would have made the diagnosis, but so would an expert clinician who has not spent 35 years studying ECGs.

Followup:

The patient returned home. Over the next week he continued to have symptoms. A week after the ED visit, he had a syncopal episode while running up stairs. EMS was called but he declined transport to the hospital. The patient’s friends would later claim that the EMS crew told him he would be fine and pressured him to sign the refusal form.

6 days after the EMS visit, the patient had a cardiac arrest.

EMS obtained ROSC and he was taken to the ED.

The patient was diagnosed with massive pulmonary emboli and admitted to the ICU.

Neurologic function did not return.

He died 5 days after the cardiac arrest.

The patient’s parents filed a lawsuit against the ED physician and hospital. They did not sue the urgent care nor the EMS service.

Multiple expert witnesses were hired including ED, cardiology, and hematology.

The only written expert report included in the court records was a hematologist for the defense.

A 10 million dollar lawsuit was successful.

Learning Points:

- A viral infection is NOT an explanation for shortness of breath.

- Learn to read ECGs.

- The PMCardio Queen of Hearts AI Model will be trained to recognize this ECG pattern. Stay Tuned.

Finally: Why don’t we have specialized electrocardiologists?

We have radiologists to read our X-rays, CT scans, and Formal Ultrasounds.

We have ultrasound fellowships for learning ultrasound in Emergency Medicine.

Why don’t we have ECG fellowships or specialized electrocardiologists? The ECG is far more difficult than ultrasound, and more important for immediate decisions than learning pelvic ultrasound or gallbladder ultrasound or appendicitis ultrasound, etc. Those are all nice, but you don’t NEED them. You can send a patient for a radiologist ultrasound etc.

(Obviously, bedside ultrasound in critically ill patients is critical — I do not include that)

But when it comes to ECGs, you are on your own. Partly that is because physicians greatly overestimate their ECG interpretation skills. So they don’t think they need help.

But, in fact, physicians are terrible at ECGs.

Anthony Kashou showed that physicians are terrible at ECG interpretation:

Kashou AH, Noseworthy PA, Beckman TJ, et al. ECG Interpretation Proficiency of Healthcare Professionals. Curr Probl Cardiol [Internet] 2023;101924. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.101924

“Among the 1206 participants, there were 72 (6%) primary care physicians (PCPs), 146 (12%) cardiology fellows-in-training (FITs), 353 (29%) resident physicians, 182 (15%) medical students, 84 (7%) advanced practice providers (APPs), 120 (10%) nurses, and 249 (21%) allied health professionals (AHPs). Overall, participants achieved an average overall accuracy of 56.4% ± 17.2%, interpretation time of 142 ± 67 seconds, and confidence of 0.83 ± 0.53.”

======================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (9/23/2025):

Today’s case was frustrating for me to read — yet extremely important for clinicians to be aware of. I did not participate in the “EKG Nerdz” group that Dr. Smith refers to in his discussion — but my impression that I made within seconds on seeing today’s ECG was identical to that of my colleague ECG enthusiasts = acute PE until proven otherwise.

Point #1: It is difficult to do quality control based on review of the medical chart. Subjective findings can be written by the clinician in a way to “cover” whatever the final discharge diagnosis turned out to be. Vital signs can be glossed over. During my 30-year academic career — the most commonly overlooked physical exam finding I observed while doing teaching rounds with medical students and residents — was respiratory rate.

- Unless you discipline yourself to do nothing other than count a patient’s respirations over a period of at least 30 seconds — the RR (Respiratory Rate) that will be written on the chart of a dyspneic patient will be routinely underestimated.

- In my experience — a notation on the chart of a respiratory rate of 12 or 16/minute in a patient who presents with dyspnea, much (if not most) of the time means that the clinician did not focus on and count respirations himself/herself for at least 30 seconds.

- Copying the respiratory rate written in the nursing notes is not an alternative for accuracy, compared to listening yourself — since in my experience, nursing documentation of respiratory rates is less than 100% accurate.

- And, IF your “well-appearing” young adult patient turns out to have a respiratory rate of say, 30/minute (with which they might not “look” to be dyspneic — because they are otherwise young and healthy and taking small, rapid breaths that go unnoticed unless you look directly at the patient and actually count how fast they are breathing) — IF they are breathing this fast, then more than a simple viral infection needs to be considered.

= = =

Point #2: Today’s patient was seen in an ED (Emergency Department). By definition — any physician in charge of seeing patients who present to an ED needs to appreciate that acute PE has to be considered until proven otherwise with a chief complaint of dypnea and an ECG that looks like today’s tracing.

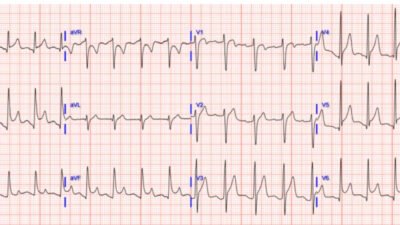

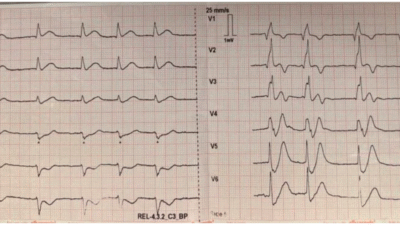

- To Emphasize: Small PEs rarely manifest RV strain on ECG. Even though most of the usual ECG findings associated with acute PE are not present in today’s initial ECG (that I’ve reproduced below in Figure-1) — RV “strain” definitely is present, in the form of symmetric T wave inversion in both anterior and inferior leads (colored arrows in Figure-1).

- PEARL (as per Drs. Smith and Meyers): When there is T wave inversion in the chest leads — IF there is T wave inversion in both lead V1 and lead III ==> Think acute PE (and not an acute coronary syndrome).

- I review ECG findings commonly associated with acute PE in My Comment in the November 21, 2024 post (in which Dr. Meyers presents links to no less than 20 cases we’ve presented in Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog of this entity).

- BOTTOM Line: Although many of the other ECG findings commonly seen with acute PE are not present in today’s case — the history of chest pain and dyspnea in an otherwise healthy young adult who presents with the ECG shown in Figure-1 has to be suspected of acute PE until proven otherwise. RV “strain” on ECG needs to be explained.

- P.S.: Technically, an S1Q3T3 pattern is not present in ECG #1 — because there is no Q wave in lead III. That said — an S wave of greater-than-usual depth in lead I in the absence of an incomplete RBBB pattern — is not usually seen in normal tracings, thereby suggesting some degree of right axis shift, which adds to my suspicion of acute PE.

- Finally — S waves do persist through to lead V6, as another finding seen in pulmonary patterns.

= = =

Figure-1: I’ve reproduced and labeled today’s ECG. (To improve visualization — I’ve digitized the original ECG using PMcardio).