Written by Jesse McLaren

A 40 year old developed sudden chest pain radiating to the jaw,

with diaphoresis and vomiting. What do you think?

What do you think?

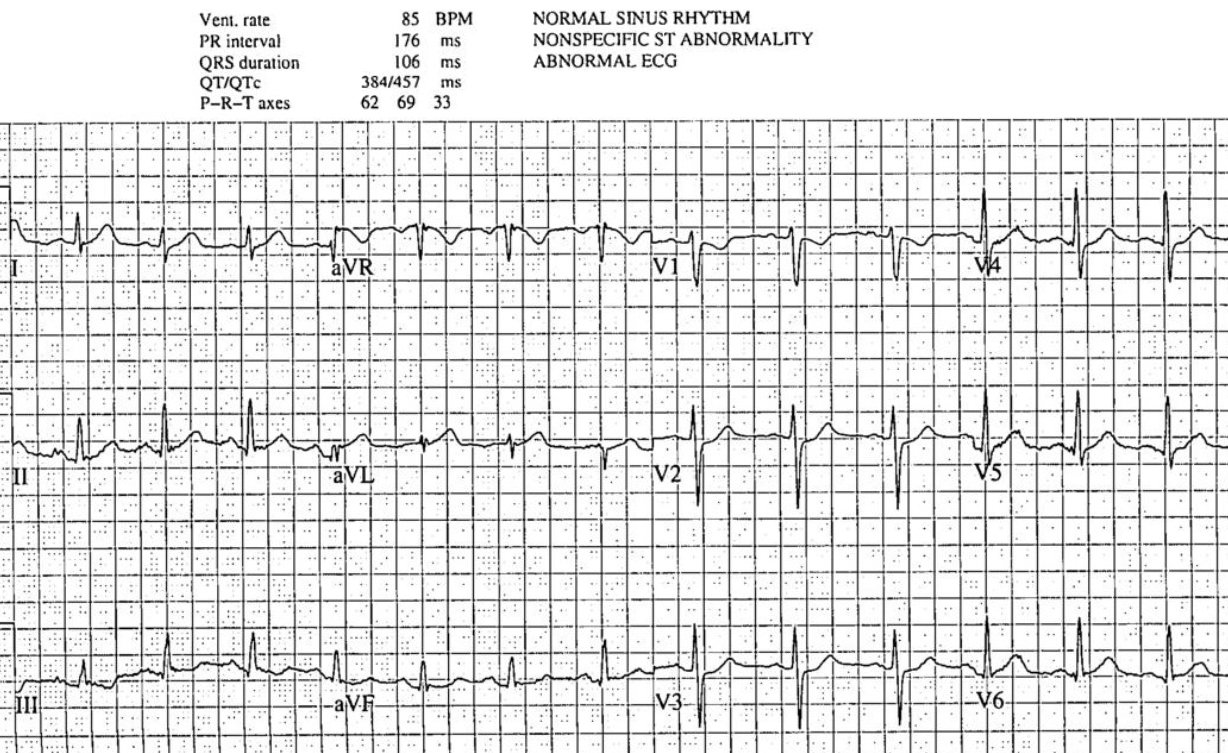

There’s normal sinus rhythm with normal conduction, normal axis,

normal R wave progression and normal voltages. There are hyperacute T wave in I/aVL

and possibly V5-6, with reciprocal change in III. There’s also ST depression in

V1-3. The computer interpretation labeled this ECG as “nonspecific”, and it

does not meet STEMI criteria. But there are ischemic abnormalities in the

majority of leads that add up to an ECG diagnostic of posterolateral Occlusion

MI.

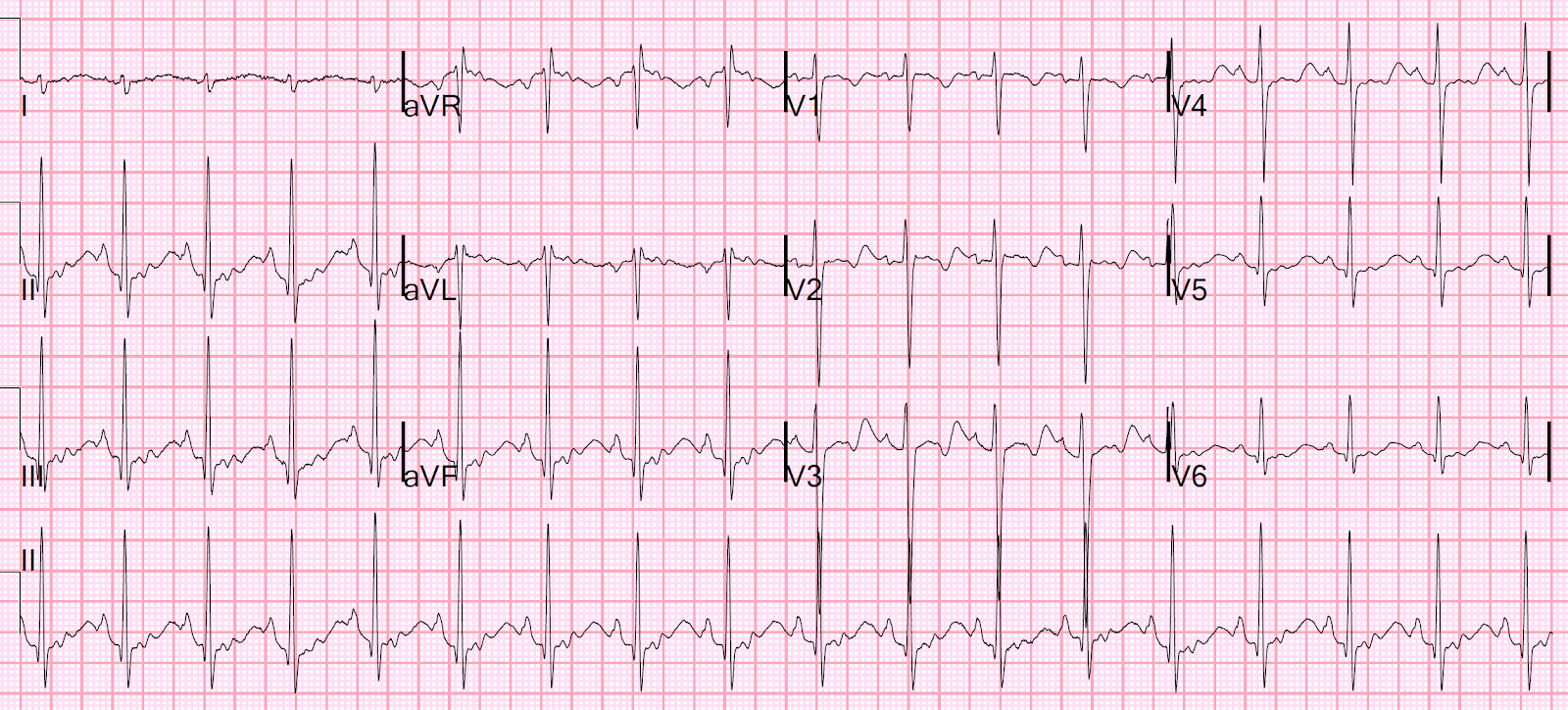

The paramedics had previously done an ECG and were concerned

about posterior MI, so they administered ASA/nitro and took the patient

directly to the cath lab. The patient arrived at the CCU with 90 minutes of ongoing

chest pain, where the ECG above was recorded followed by a 15-lead ECG 4

minutes later.

There’s now an acute Q wave and convex ST segment in aVL,

and mild ST elevation in the posterior leads V8-9, again confirming

posterolateral OMI. But the cardiologist did not think it met STEMI criteria, so

the patient was sent to the emergency department for assessment.

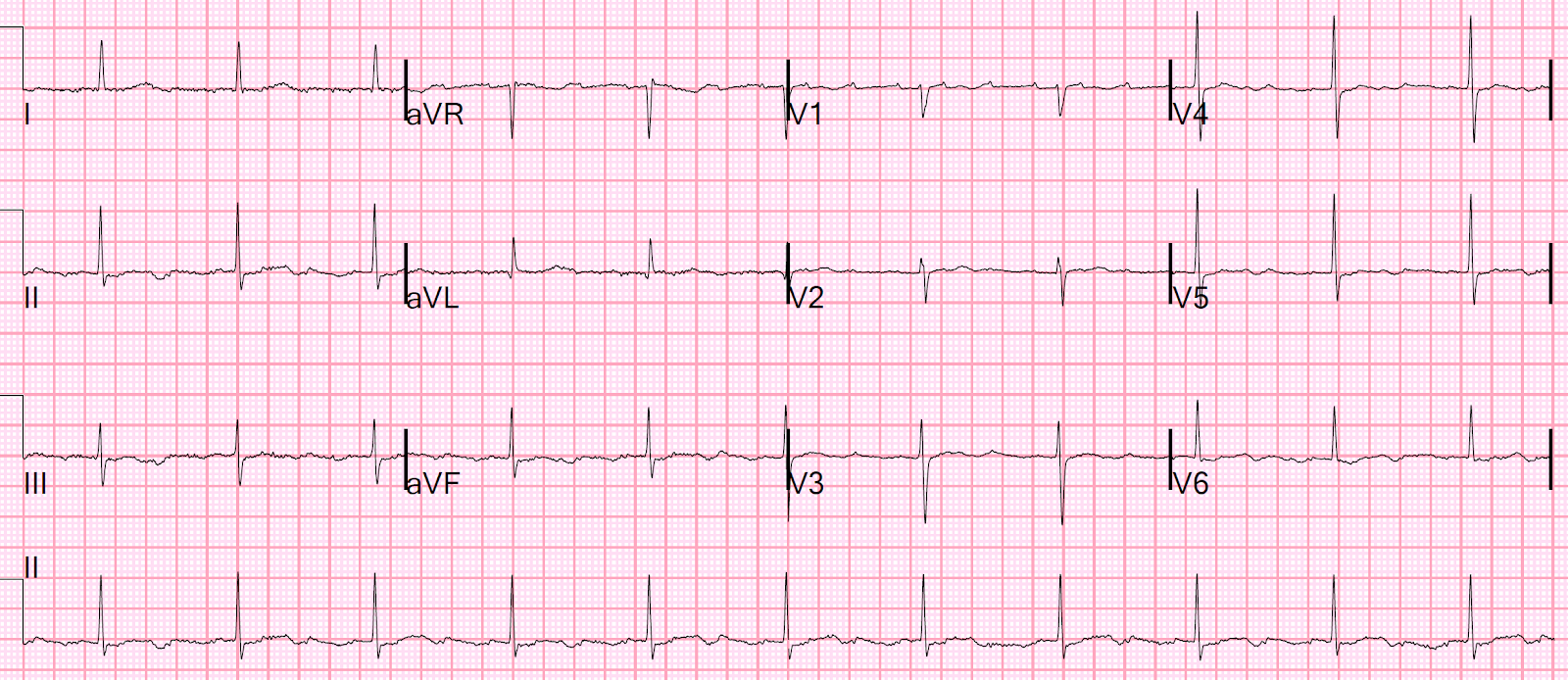

The patient arrived in the ED with ongoing chest pain and

another ECG was obtained:

There’s now mild ST elevation in I/aVL and deeper ST

depression in V3, confirming ongoing posterolateral OMI. The emergency

physician gave more nitro and called a Code STEMI.

Cardiology assessed the patient in the ED with serial ECGs

over the next hour, during which time the chest pain continued and the first high sensitivity troponin I returned at 100 ng/L (normal <26).

There’s ongoing posterolateral OMI, in a patient with refractory

chest pain and positive troponin. But cardiology felt this did not consistently

meet STEMI criteria, and noted the pain was reproducible on palpation and

unrelieved by nitro, so they administered morphine and asked for a CT chest to

rule out dissection. But reproducible or other forms of atypical chest pain do not exclude myocardial

infarction in a patient with such a high pre-test likelihood; morphine is

associated with delayed reperfusion; and refractory ischemic chest pain is an

indication for the cath lab even in the absence of ECG changes.

The CT found coronary calcifications but no aortic

dissection. The patient was still in pain, with a repeat troponin of 400 ng/L.

Cardiology reassessed the patient and diagnosed NSTEMI, treated with

ticagrelor/heparin/nitro and non-urgent cath. Because of refractory chest pain

the patient received multiple doses of morphine for another couple of hours in

the emergency department, and then was taken to the cath lab. Angiogram found a

99% occlusion of the first obtuse marginal, as predicted from the first ECG, with TIMI-1 flow.

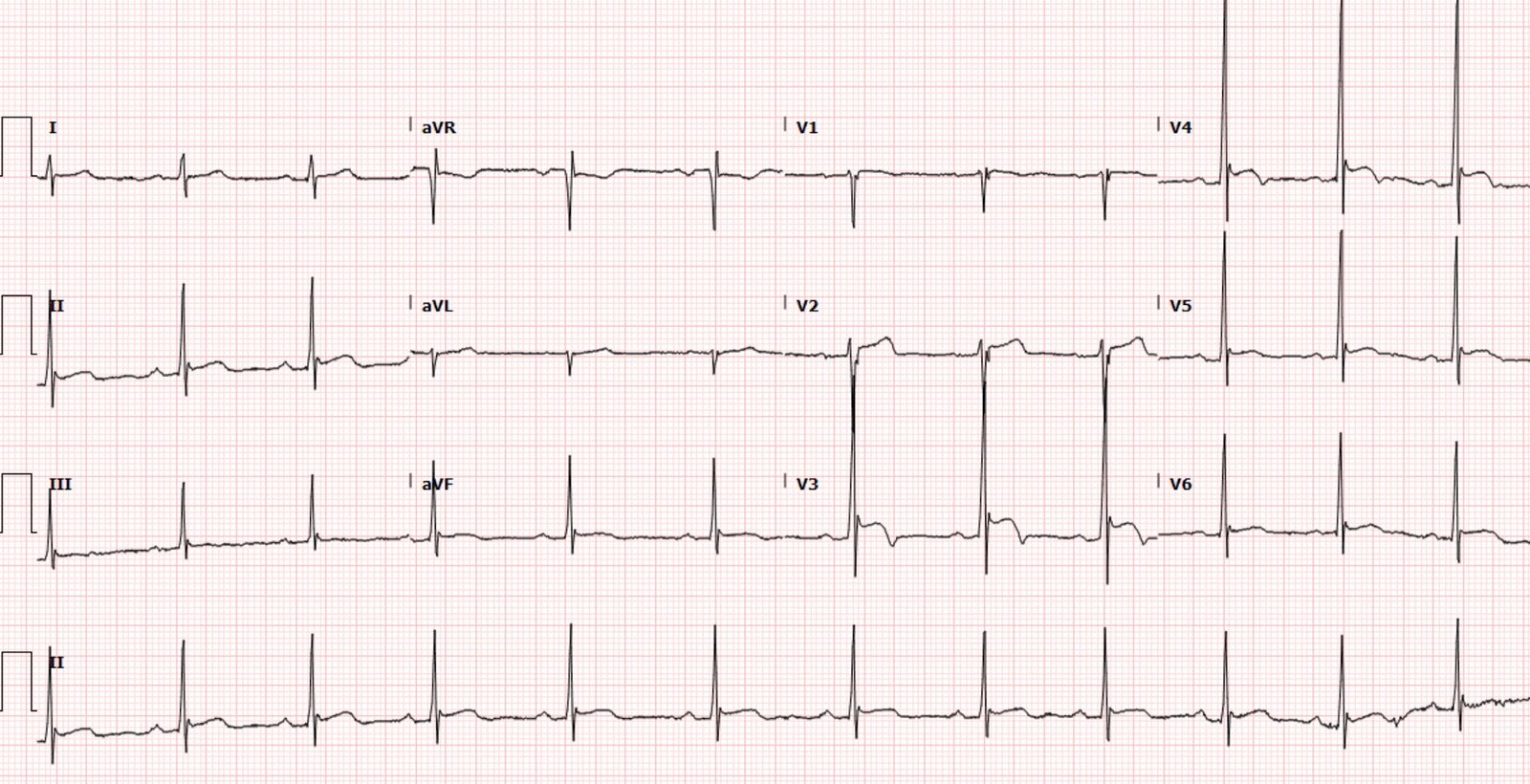

Below is the next day ECG:

T waves in I/aVL/V6 have deflated to their normal size and

developed reperfusion T wave inversion, with ongoing Q wave in aVL, and taller

T waves in the anterior leads from posterior reperfusion.

Peak troponin was 50,000 ng/L and the echo found an EF of 50%

with basal/lateral wall motion abnormalities. The discharge diagnosis was “NSTEMI,” implying that the cath lab activation was false and the cancellation was appropriate.

False/inappropriate activation or cancellation?

There are many

studies on false positive and inappropriate activation of the cath lab. “False positive

activation” is a retrospective term for patients whose angiogram reveals no

culprit lesion.(1-7) But this is a heterogeneous group, including “appropriate

false-positive activation” (including STEMI mimics like takotsubo, coronary

spasm or myocarditis, which can only be diagnosed after angiogram has ruled out

acute coronary occlusion) and “unnecessary cath lab activation” (erroneous ECG

interpretation and MI ruled out).(8) Unfortunately, “inappropriate activation”

has come to mean any cath lab activation that is canceled by the cardiologist

because the ECG didn’t meet STEMI criteria. This defines “appropriateness” by the surrogate marker of STEMI criteria, not the actual outcome of acute coronary occlusion. If the cath lab is activated for STEMI(+)NOMI (e.g non-ischemic elevation from LVH or early repol, with a non-occlusive lesion with TIMI-3 flow) this could still be classified as appropriate; yet cath lab activation for STEMI(-)OMI (i.e does not meet STEMI criteria but does have an occluded artery) could be considered inappropriate. Many

studies have excluded “inappropriate activation” patients from further

analysis, and gone onto classify the “appropriate activations” as true positive

STEMI vs false positive STEMI. (9-11) But what about false negative STEMIs, false cancellations and

inappropriatecancellations, like our patient above?

According to the

STEMI paradigm, there’s no such thing as a false negative STEMI, because this

is by definition “Non-STEMI”—even though 25-30% of NSTEMI have a totally occluded

artery and double the mortality.(12) This is what Smith/Meyers have termed the

“no false negative paradox.” Even those studies that have looked at outcomes of

“inappropriate activation” have denied the possibility of false negative STEMI.

Mixon et al. have a figure that illustrates this:

According to this classification, activations based on STEMI

criteria are deemed appropriate and classified as either true positive or false

positive based on the angiogram, but activations without STEMI criteria are by

definition inappropriate and false positive regardless of angiogram findings—even

though 41% of this group was subsequently diagnosed as “NSTEMI/UA”, a

heterogenous group including STEMI(-)OMI, NOMI and unstable angina.(13) Shamim

et al. found 5 of 62 “inappropriate activations” (8%) required emergent cath

but all were diagnosed with “Non-STEMI.”(14) Similarly, Degheim et al found 2

of 37 cancellations (5.4%) were “erroneously cancelled and found to be actual

STEMIs when patients underwent coronary angiography later for unresolved chest

pain and positive biomarkers.”(15) But these patients were not “actual STEMIs”, they

were STEMI(-)OMIs.

If false negative

STEMI doesn’t exist, then neither does inappropriate cath lab cancellation—even

if it results in patient death like this case or this case. There is only one study on

inappropriate cath lab cancellation, but this was defined as ECGs that met

STEMI criteria, in a patient with typical chest pain ≤12

hours, who had no contraindications but was not taken for cath, and ruled in

for MI.(16)

Only 1% of cancellations met this narrow definition, but 18% were canceled

because of “ST-T changes not consistent with STEMI,” 25% were canceled because of

bundle branch block or paced rhythm, and 10% required PCI. How many of these were

inappropriate cancellations, with ECGs diagnostic of STEMI(-)OMI?

“Appropriate

cath lab activation” should be based on the patient outcome that benefits from emergent

reperfusion—acute coronary occlusion—and criteria for cath lab activation

should be expanded beyond classic STEMI criteria to incorporate the latest advances.(17)

This now include evidence-based ECG criteria that can identify OMI and

differentiate it from mimics,(18) which is twice as sensitive as STEMI criteria

with preserved specificity (19). The STEMI paradigm has restricted its quality

metrics like door-to-balloon time to STEMI(+)OMI, but we need to apply them to

all patients with acute coronary occlusion including STEMI(-)OMI.(20). If we

use balancing measures like false or inappropriate activation to monitor and prevent against

over-activation of the cath lab, shouldn’t we also track false or inappropriate

cancellation to monitor and prevent delayed reperfusion?

Take home:

1.

Primary ST depression V1-4 is posterior OMI

until proven otherwise. A 15 lead may or may not show ST elevation, but can also show dynamic anterior and inferior/lateral changes

2.

Lateral OMI can be subtle but can often be

identified by acute Q waves, subtle ST elevation, convex ST segments,

hyperacute T waves, and inferior reciprocal change

3.

Reproducible chest pain does not rule out OMI in

high pre-test patients, and morphine is associated with delayed reperfusion

4.

Rather than restricting “Code STEMIs” to

STEMI(+)OMI, appropriate cath lab activation needs to be expanded to include

ECG signs of STEMI(-)OMI and clinical signs like refractory ischemia

5.

When the cath lab is canceled for lack of STEMI

criteria, but patients are subsequently found to have an acute coronary

occlusion, this should not be labeled “NSTEMI” with “appropriate cancellation”

but STEMI(-)OMI with inappropriate cancellation

References:

1. Larson. ‘False-positive’ cardiac

catheterization laboratory activation among patients with suspected ST-segment

elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA 2007

2. Yougquist et al. A comparison of

door-to-balloon times and false-positive activations between emergency

department and out-of-hospital activation of the coronary catheterization team.

Acad Emerg Med 2008

3. Nfor. Identifying false-positive

ST-elevation myocardial infarction in emergency department patients. J of Emerg

Med 2012

4. Chung et al. Characteristics and

prognosis in patients with false-positive ST-elevation myocardial infarction in

the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2013

5. Groot et al. Characteristics of patients

with false-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction diagnoses. Eur Heart J

2016

6. Shoaib et al. Impact of pre-hospital

activation of STEMI on false positive activation rate and door to balloon time.

Heart, Lung and Circ 2022

7. McCabe et al. Prevalence and factors

associated with false-positive ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

diagnoses at primary percutaneous coronary intervention-capable centers: a

report from the Activate-SF Registry. Arch Intern Med 2012

8. Kontos et al. An evaluation of the accuracy

of emergency physician activation of the cardiac catheterization laboratory for

patients with suspected ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Emerg

Med 2010

9. Lu et al. Incidence and characteristics

of inappropriate and false-positive cardiac catheterization laboratory

activations in a regional primary percutaneous coronary intervention program.

Am Heart J 2016

10. Boivin-Proulx et al. Effect of real-time

physician oversight of prehospital STEMI diagnosis on ECG-inappropriate and

false positive catheterization laboratory activation. CJC Open 2021

11. Garvey et al. Rates of cardiac

catheterization cancelation for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

after activation by emergency medical services or emergency physicians: results

from the North Carolina Catheterization Laboratory Activation Registry. Circ

2012

12. Khan et al. Impact of total occlusion of

culprit artery in acute non-ST elevation myocardial infarction: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2017

13. Mixon. Retrospective description and

analysis of consecutive catheterization laboratory ST-segment elevation

myocardial infarction activations with proposal, rationale, and use of a new

classification scheme. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012

14. Shamim et al. Electrocardiographic

findings resulting in inappropriate cardiac catheterization laboratory

activation for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Diagn

Ther 2014

15. Degheim et al. False activation of the

cardiac catheterization laboratory: the price to pay for shorter treatment

delay. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis 2019

16. Lange et al. Cancellation of the cardiac

catherization lab after activation for ST-segment-elevation myocardial

infarction: frequency, etiology, and clinical outcomes. Circ Cardiovas Qual

Outcomes 2018

17. Rokos et al. Appropriate cardiac cath lab

activation: optimizing electrocardiogram interpretation and clinical

decision-making for acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2010

18. Aslanger, Meyers, Smith. Recognizing

electrocardiographically subtle occlusion myocardial infarction and

differentiating it from mimics: ten steps to or away from the cath lab. Turk

Kardiyol Dern Ars 2021

19. Meyers et al. Accuracy of OMI ECG

findings versus STEMI criteria for diagnosis of acute coronary occlusion

myocardial infarction.

20. McLaren, Meyers, Smith, et al. From

STEMI to occlusion MI: paradigm shift and ED quality improvement. CJEM 2021