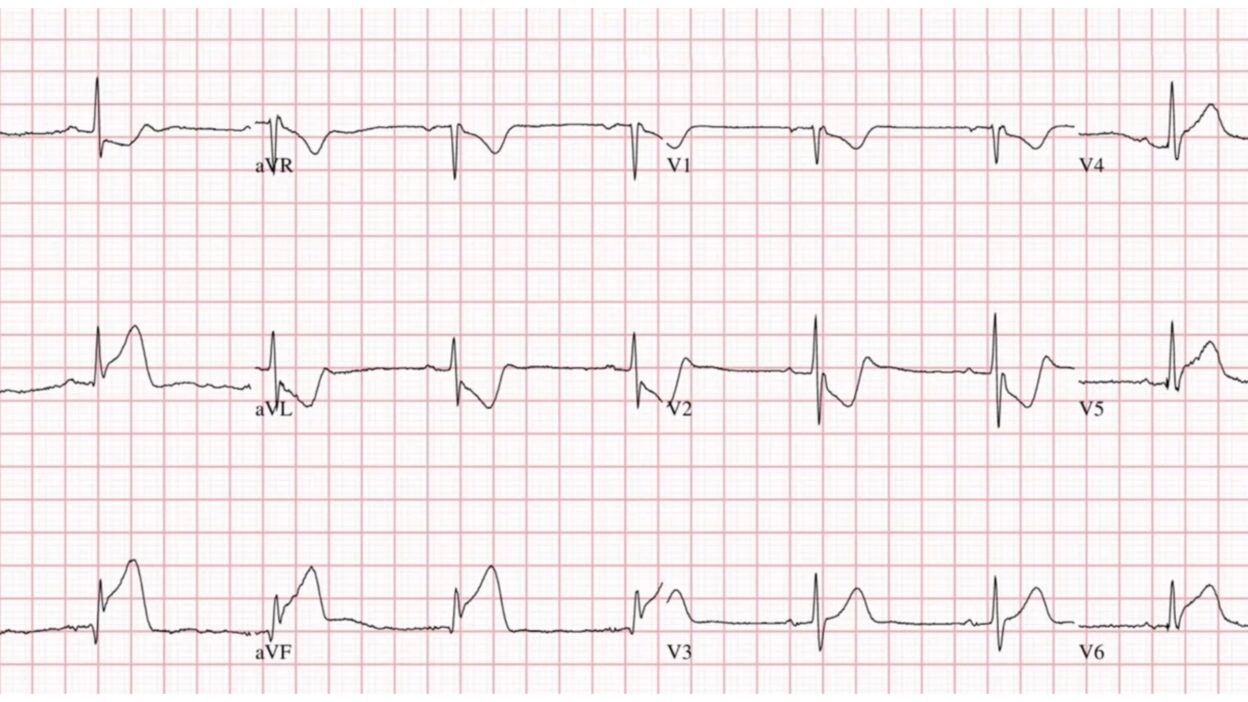

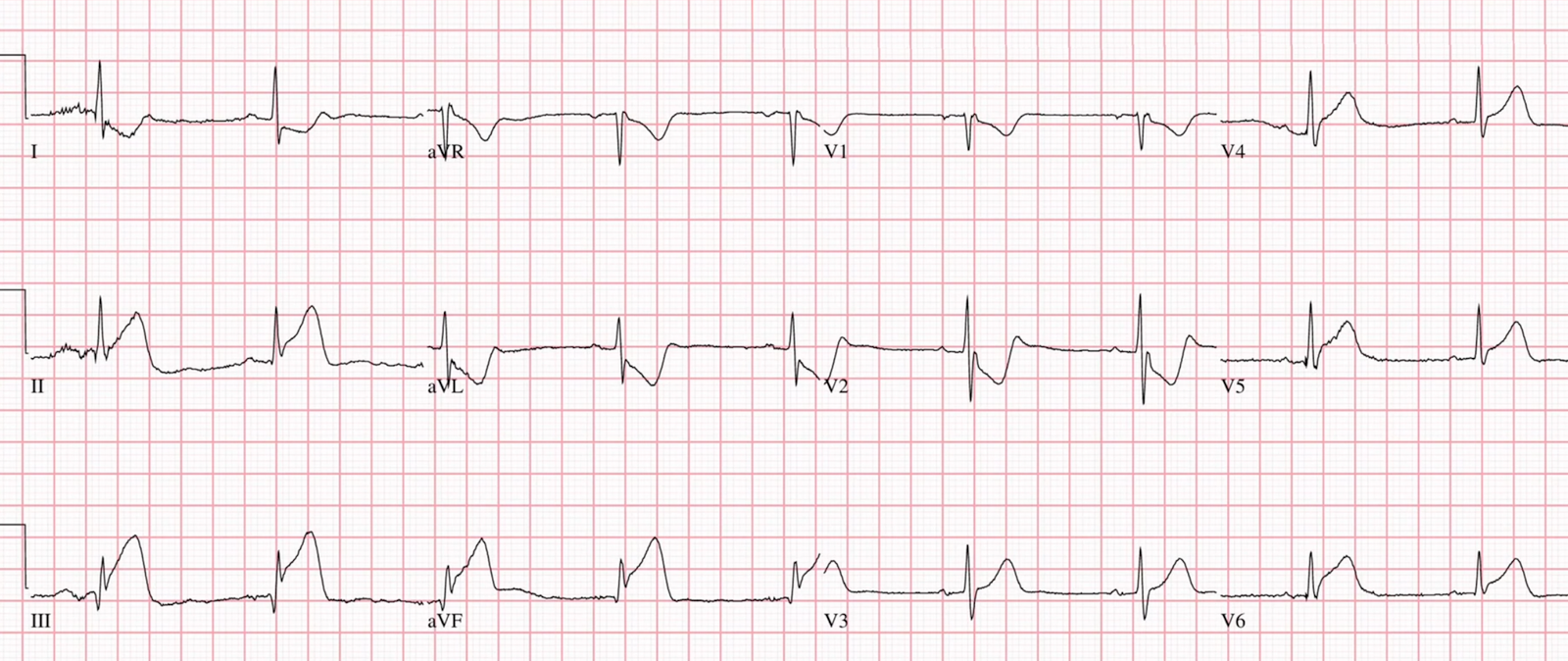

A 45-year-old man presented to the ED complaining only of “heartburn”. There was no chest pain, no shortness of breath, nausea or vomiting. And this was his ECG …

The diagnosis is obvious — but there is more. What do you think? (See below).

The patient had mostly normal blood pressure, but did have one BP measured at 93/51.

Watch this video breaking down this ECG case and see what happened!

Watch the Video and listen to Sam’s excellent narration.

This is a large MI (of inferior, posterior, and lateral walls, with Right ventricular MI!). RV MI often presents with hypotension and RV failure, which is very dangerous. Unlike the LV, the RV depends on systolic blood pressure for perfusion. If the BP falls, the perfusion falls (especially through collaterals) and then cardiac output and BP fall further in a vicious circle of death.

RV MI is VERY dangerous

—Zehender M, et al. Right ventricular infarction as an independent predictor of prognosis after acute inferior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993;328(14):981–8. —The patients with ST-segment elevation in lead V4R had a higher in-hospital mortality rate (31 percent vs. 6 percent, P<0.001) and a higher incidence of major in-hospital complications (64 percent vs. 28 percent, P<0.001) than did those without ST elevation in V4R.

—Zehender et al. (#2). Zehender M, Kasper W, Kauder E, Geibel A, Schonthaler M, Olschewski M. Eligibility for and benefit of thrombolytic therapy in inferior myocardial infarction: focus on the prognostic importance of right ventricular infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;24(2):362–9.—–Patients with RV MI who received reperfusion therapy had 10% mortality; those who did not had 42% mortality.

Bischof and Smith studied the utility of STE in V1 for diagnosis of RV MI in the setting of inferior OMI: Specificity of STE in V1 for RVMI was 84%; sensitivity was 35%. Sensitivity was higher without (69%), than with (35%), STD in V2. In other words, ST depression in V2 hides RV MI, just as in this case.

Not all proximal RCA Occlusions result in RV MI physiology (hypotension, poor RV systolic function) because there are often collaterals from the LAD to the RV.

Epigastric pain in acute MI: Not only is acute MI often the etiology of epigastric pain, but a “GI cocktail” will often be associated with resolution of pain (in some studies, 25% of the time!). This is presumably just coincidence, because acute spontaneous reperfusion is very common, leading to resolution of symptoms. NEVER make any diagnosis based on therapeutic trials. One can never distinguish GI symptoms from MI without ECG +/- troponin.

Here is a great example, with a very subtle ECG: ST depression limited to Inferior leads is reciprocal to high lateral wall and represents STEMI. Patient diagnosed with Acid Reflux, sent home and had a cardiac arrest.

= = =

======================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (10/19/2025):

Today’s case by Dr. Ghali highlights a series of important points:

- A chief complaint of severe “heartburn” that persists, unrelieved by the usual treatment measures — is a worrisome sign. (GI complaints tend to be more common with inferior MI — attributable to the anatomic location of the inferior wall of the left ventricle that “sits” on the diaphragm).

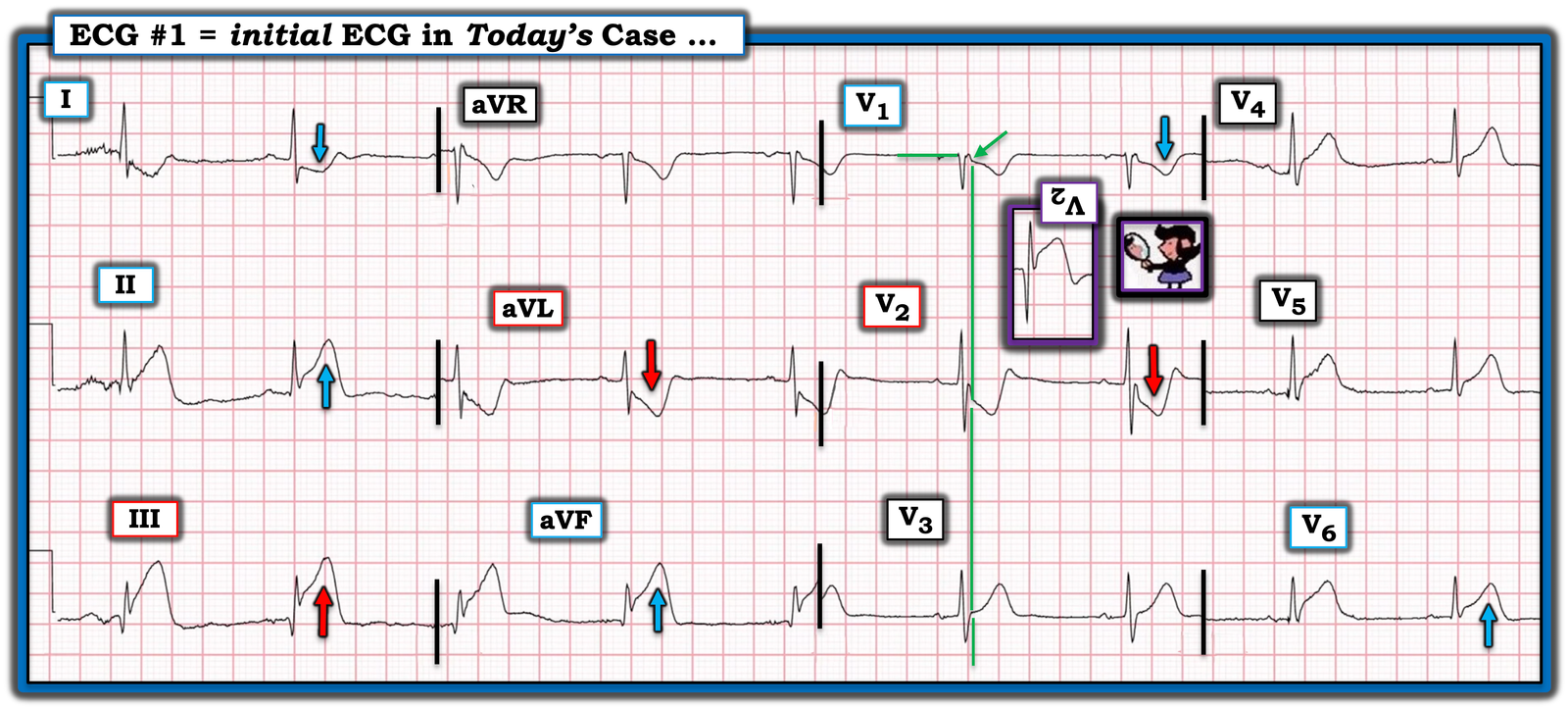

- Sometimes the magnitude of ECG abnormalities in a given patient will surprise you. For example — I would not have imagined the profound amount of ST-T wave deviation seen in today’s initial ECG (that I’ve reproduced and labeled in Figure-1).

- The sinus bradycardia that we see in Figure-1 is part of the overall process. Acute MI is known to produce changes in the autoregulation of autonomic tone (affecting both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems). In general — acute MI results in parasympathetic dysfunction, in the form of a reduction in the amount of “protective” vagal tone. A lessening of vagal tone upsets autonomic balance — with resultant unopposed sympathetic activation that predisposes to tachycardia with an increased risk in potentially lethal MI-associated arrhythmias ( = VT/VFib).

- KEY Point: Because inferior MIs are significantly less often affected by this autoregulatory reduction in parasympathetic tone — sinus bradycardia is much more common in association with acute inferior MI (whereas sinus tachycardia is more common with anterior MI — Wu and Vaseghi — Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 43(2):172-180, 2020 — and — McAreavey et al — Heart 62(3):165-170, 1989 ).

- “A picture is worth 1,000 words …” — The Echo clip in the above ECG Video by Dr. Ghali instantly told him much more than what he might have learned from the ECG finding of ST elevation in right-sided leads. Looking at this Echo clip (that occurs at 4:25 minutes in the above Video) — we can instantly appreciate the marked degree of RV dilatation, with its profound depressive effect on contractility.

- In the hands of a skilled emergency physician — bedside Echo is fast and provides invaluable information (which is the reason Dr. Ghali prefers it to obtaining right-sided leads when assessing a patient for acute RV involvement). That said — immediate Echo performed by skilled operators will not always be available in all clinical settings — in which case I advocate for use of right-sided leads to supplement standard ECG monitoring.

- As emphasized in many posts on Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog (See My Comment at the bottom of the page in the July 19, 2020 post) — awareness of acute RV involvement is clinically important for a number of reasons: i) It localizes the acute coronary occlusion to the proximal RCA (as is impressively demonstrated at 5:02 minutes in Dr. Ghali’s Video clip from this patient’s cardiac catheterization); — and, ii) Prognosis and management of acute inferior MI with significant RV involvement is often associated with poorer outcome + hypovolemia with hypersensitivity to nitroglycerin that may precipitate hypotension + depressed RV function (as is evident in Dr. Ghali’s Echo clip).

- Overall — acute inferior MI is associated with some degree of acute RV involvement in more than 1/4 of cases. That said — in many of these cases, LV dysfunction is the primary problem, and the degree of RV dysfunction is of limited clinical significance. Thus the goal for optimal management is to recognize those cases of acute RV MI in need of fluid resuscitation and intense hemodynamic monitoring (Jeffers et al — StatPearls, 2023 — and, Ondrus et al — Exp. Clin Cardiol 18(1):27-30, 2013 ).

= = =

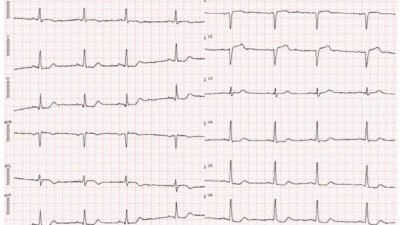

ECG Diagnosis of acute RV Infarction:

- Because none of the standard 12 ECG leads directly view the RV — the sensitivity of the ECG for detecting acute RV MI is not optimal. This means that much of the time — you will not be able to rule out the possibility of acute RV MI from exclusive use of the standard 12 leads. That said — lead V1 comes closest to viewing electrical activity in the right ventricle. As a result — IF there is abnormal ST elevation in lead V1 (but not in other anterior leads) in association with new-onset chest pain and acute inferior lead ST elevation — then the standard 12-lead ECG can be strongly suggestive of acute RV MI from acute proximal RCA occlusion. (For just one example of ECG diagnosis of acute RV MI from the standard 12 leads — Check out the October 7, 2019 post, with attention to My Comment at the bottom of the page).

- NOTE #1: Right-sided chest lead ST elevation in association with acute RV MI tends to be transient! Right-sided ST elevation has been shown to resolve in up to 50% of patients with acute RV MI within 12 hours of the onset of symptoms! (Nagam et al — Perm. J 2017 ;21:16-105).

- NOTE #2: When precordial leads are placed on the right side of the chest — lead V2 becomes right-sided lead V1 ( = V1R) — and — lead V1 becomes right-sided lead V2 ( = V2R). Although some providers prefer leaving standard leads V1 and V2 unchanged, and recording leads V3R-thru-V6R when getting right-sided leads — I prefer reversing chest lead placement of all 6 leads.

- The BEST single right-sided lead to use when assessing for acute RV MI is lead V4R. When there is ≥1 mm of ST elevation in lead V4R — this approaches 100% sensitivity and over 90% predictive accuracy for detecting acute RV MI (Jeffers et al — StatPearls, 2023).

- Other parameters that have been cited as predictive of acute RV MI include: i) ST elevation in any of the other right-sided leads; — and, ii) Progressive increase in the relative amount of right-sided ST elevation as one moves rightward from lead V1R-to-lead V6R.

= = =

The ECG in Today’s CASE:

For clarity in Figure-1 — I’ve labeled today’s ECG with the findings highlighted by Dr. Ghali in his ECG Video:

- There is sinus bradycardia at ~55/minute.

- The diagnosis of an acute inferior STEMI is obvious from the marked inferior lead ST elevation (greatest in lead III) — with developing Q waves — and mirror-image opposite reciprocal ST depression in lead aVL (and to a lesser extent in lead aVL).

- As per Dr. Ghali — the RCA (Right Coronary Artery) is suggested as the “culprit” artery because: i) ST elevation in lead III is greater than in lead II; — ii) There is marked reciprocal ST depression in lead aVL, more than in lead I; — and, iii) The amount of ST elevation in lead III is greater than in lead V6 (as opposed to LCx occlusion — which would be more likely to show more ST elevation in lead V6).

- Acute posterior OMI is diagnosed by the marked ST depression in lead V2 ( = the positive Mirror Test — See My Comment at the bottom of the page in the September 21, 2022 post for more on the Mirror Test).

- Finally (as per Dr. Ghali) — lead V1 in Figure-1 suggests that there is associated acute RV involvement because the amount of ST-T wave depression in this lead is relatively small compared to the massive ST-T wave depression in neighboring lead V2. Typically with acute posterior OMI — lead V1 will look more like lead V2 than it does here unless some of the ST-T wave depression that would have been seen in lead V1 is being attenuated by ST elevation from simultaneously occurring acute RV MI.

- NOTE: There actually is slight J-point ST depression in lead V1 — as highlighted by the GREEN arrow in this lead (the vertical GREEN line marking the end of the QRS complex in leads V1,V2,V3 — thereby showing that the J-point in lead V1 is indeed depressed).

= = =

Figure-1: I’ve labeled the initial ECG.

= = =

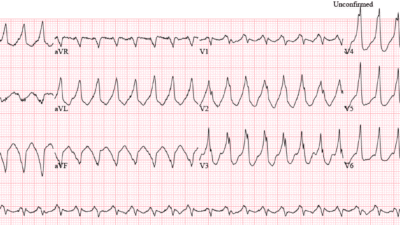

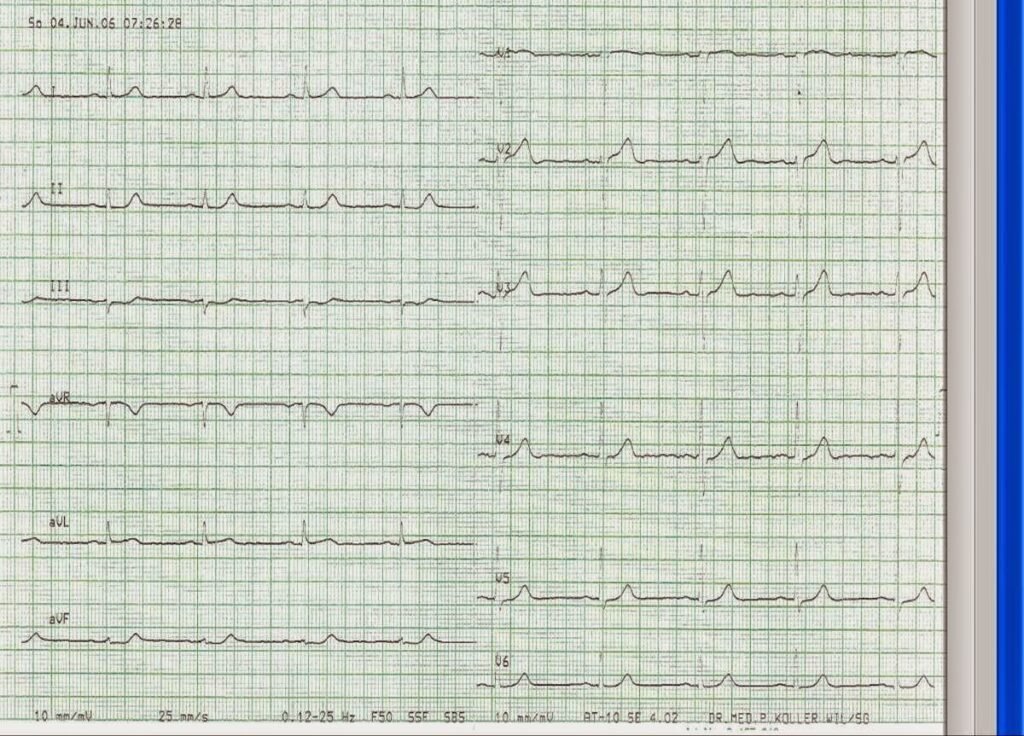

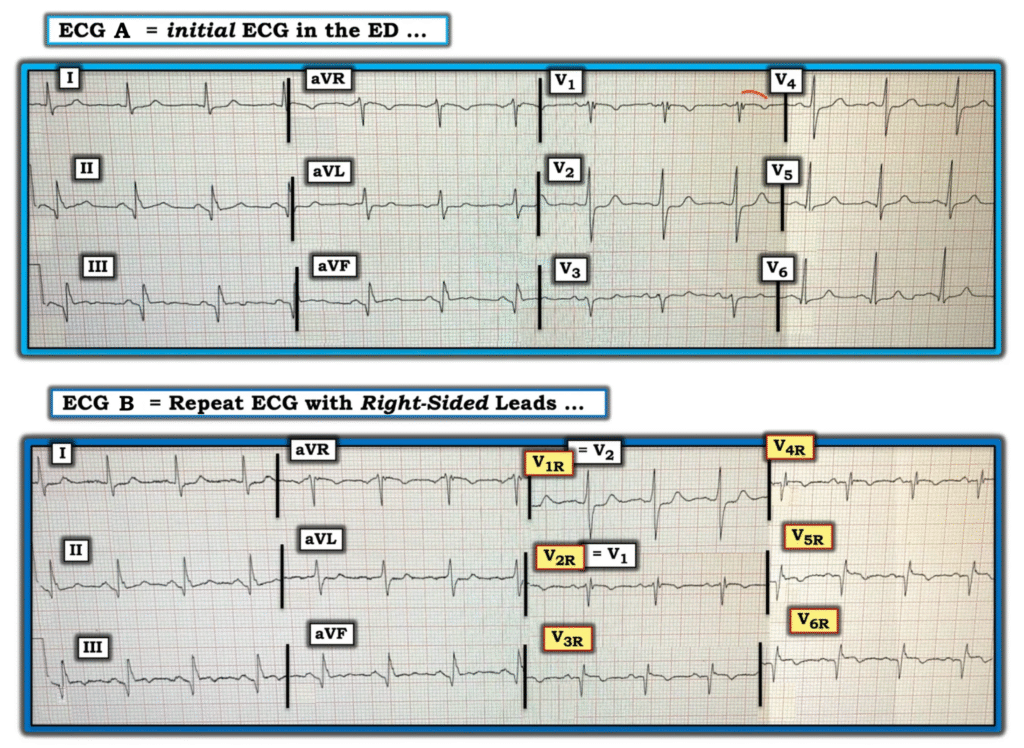

What Positive RV Leads Look Like:

I’ve excerpted Figure-2 below from the July 19, 2020 post — as an example of right-sided leads that are diagnostic of acute RV MI.

- ECG A in Figure-2 shows a sinus rhythm with evidence of infero-postero MI having occurred at some point in time as diagnosed by: i) Q waves with subtle ST elevation in leads II,III,aVF — and with subtle reciprocal changes in lateral leads I,aVL; — and, ii) Early transition with a tall R wave already in lead V2 — in association with shelf-like ST depression in this lead. That said, as a single tracing without more information and without a prior ECG for comparison — it would be difficult to tell if the above noted changes were new or old.

- The coved ST segment with T wave inversion in lead V1 is suspicious but nondiagnostic of RV involvement — because with posterior infarction, we would expect an ST-T wave in lead V1 to look more like what we see in lead V2.

But look at what happens in ECG B with right-sided leads:

- With placement of right-sided leads — lead V2 becomes right-sided lead V1 ( = V1R) — and — lead V1 becomes right-sided lead V2 ( = V2R).

- Beginning with lead V2R — there is ST elevation in 5 consecutive right-sided leads. Right-sided ST elevation is maximal in leads V5R and V6R. These right-sided ECG findings confirm acute RV MI!

= = =

Figure-2: An example of diagnostic right-sided leads (adapted from the July 19, 2020 post in Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog).

= = =

= = =