Written by Lucas Goss MD, peer reviewed by Pendell Meyers, Alex Bracey, Stephen Smith

An 81 year-old female with PMHx of ESRD on hemodialysis, normal NM stress test in

2020, TAVR on warfarin, atrial fibrillation, diastolic heart failure, obesity, diabetes,

hypertension, and CVA was brought into the ED by EMS for altered

mental status and hypotension that began near the end of her dialysis session. Upon

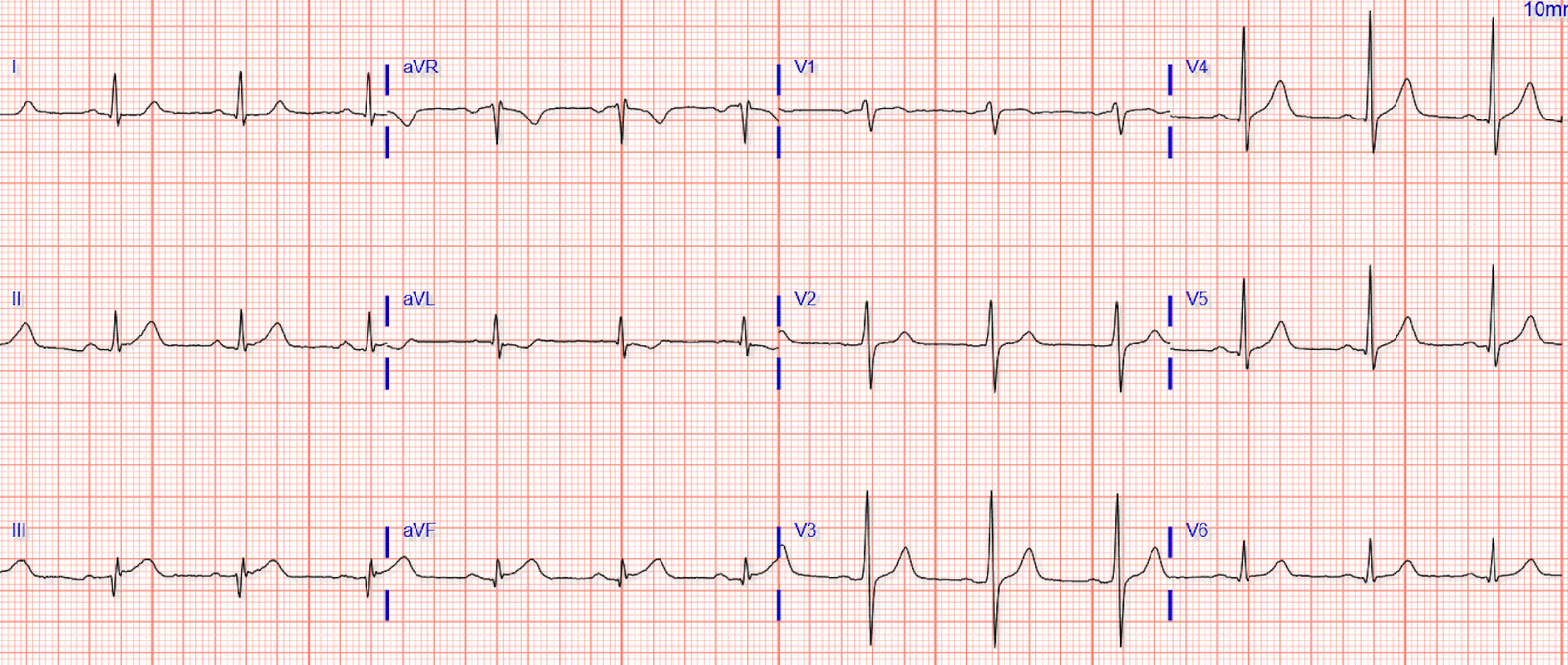

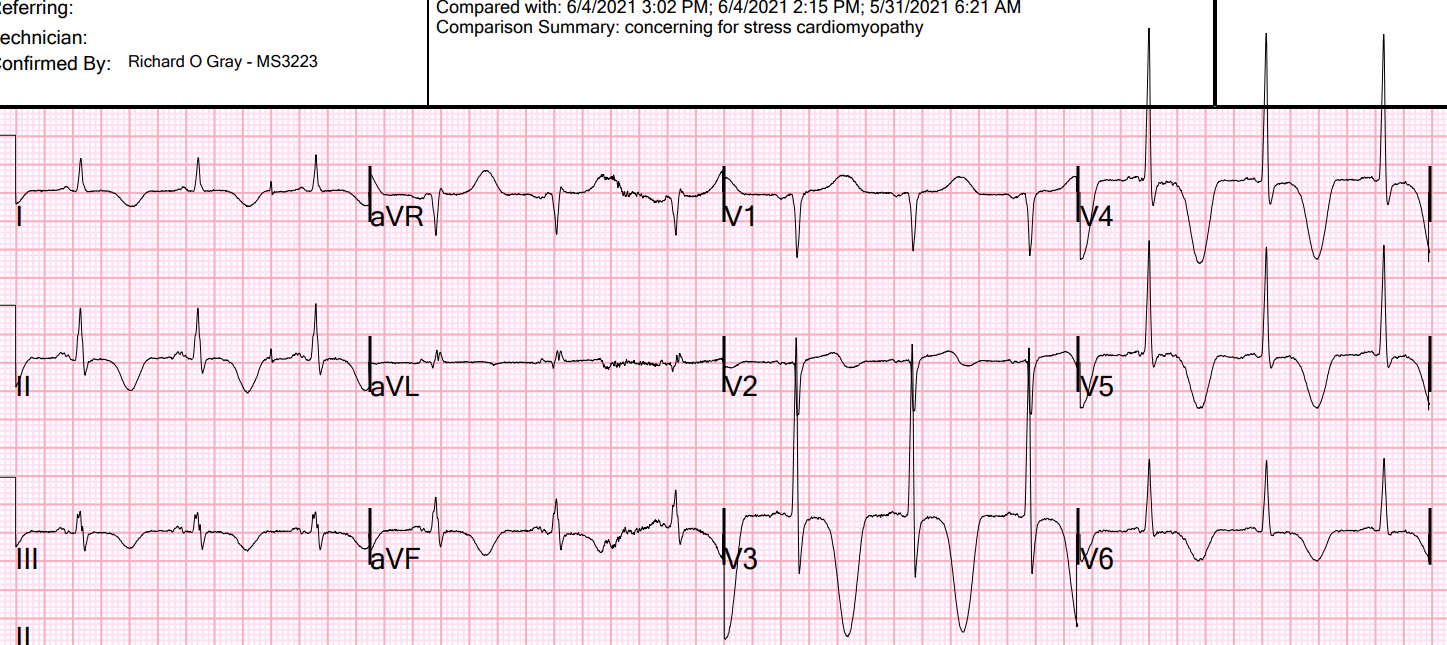

EMS arrival to her dialysis facility, they were unable to obtain a blood pressure. EMS recorded a prehospital ECG that looked identical to the initial ED ECG shown below, and EMS called the ED physician concerned about the patient and the ECG, asking whether the cath lab should be activated:

|

| What do you think? |

ECG Interpretation

Sinus rhythm 1st degree AV block, with a few PACs or PJCs (causing a few periods of regularly irregular rhythm)

The QRS is approximately 100ms, with morphology suggestive of LAFB

Diffuse ST depression that is maximal in V4-V6 and lead II, with obligatory reciprocal STE in aVR

Impression

Findings consistent with diffuse supply demand mismatch, without signs of focal occlusion. As we have explained many times on this blog, the differential of this ECG pattern is huge, including non-occlusive ACS (such as acute left main ACS, triple vessel disease with nonocclusive culprit), or any non-ACS cause of either/both decreased supply or decreased demand. The list of causes for this latter possibility is far too long to list, but common causes include hypotension, hypoxemia, sepsis, GI bleed, etc.

Case Continued

Before the patient had arrived in the ED, the ED providers were initially concerned for ACS because of “aVR sign”. Because of this concern, they immediately paged cardiology and asked that they come down to the ED to evaluate the patient on arrival. The patient was immediately brought back to a resuscitation room.

Upon arrival to the ED, the patient’s vital signs were notable for BP of 82/67, HR in the 60’s, and saturating well on room air. From the available documentation, it sounds like the patient was somewhat somnolent on arrival, and it is unclear to me whether she could confirm or deny chest pain or other symptoms.

The patient was

undressed and noted to have a massive amount of melena. At this point the working diagnosis was changed to massive GI bleeding.

A central line was placed and she began receiving massive transfusion protocol, TXA, and vasopressors. She

was found to be acidotic with a hgb of 5.4 (down from 9.7 one week earlier), lactate of

12, INR was unreadably high, and significant elevation of LFTs. Initial troponin was 89.

After intubation she lost pulses and suffered a brief PEA arrest that responded to 1mg

of epinephrine and 1 round of compressions.

Unfortunately she remained too unstable for endoscopy and continued to have GI

bleeding. She suffered another cardiac arrest and was made DNR shortly into her

hospital stay.

Learning Points

STE in AVR with diffuse ST depression is NOT diagnostic of left main or severe triple

vessel disease. Rather, it is most commonly representative of diffuse subendocardial

ischemia or supply/demand mismatch. The causes of this finding are vast and include

sepsis, hypoxia, PE, tachyarrhythmias, GI bleeding, etc., as well as ACS. It depends almost completely on the clinical situation.

Note that this is in contrast to ST depression in leads V1-V4 which is typical of posterior

OMI. With diffuse subendocardial ischemia, there will be STE in AVR with diffuse ST

depression that is maximal in V5, V6, and lead II.

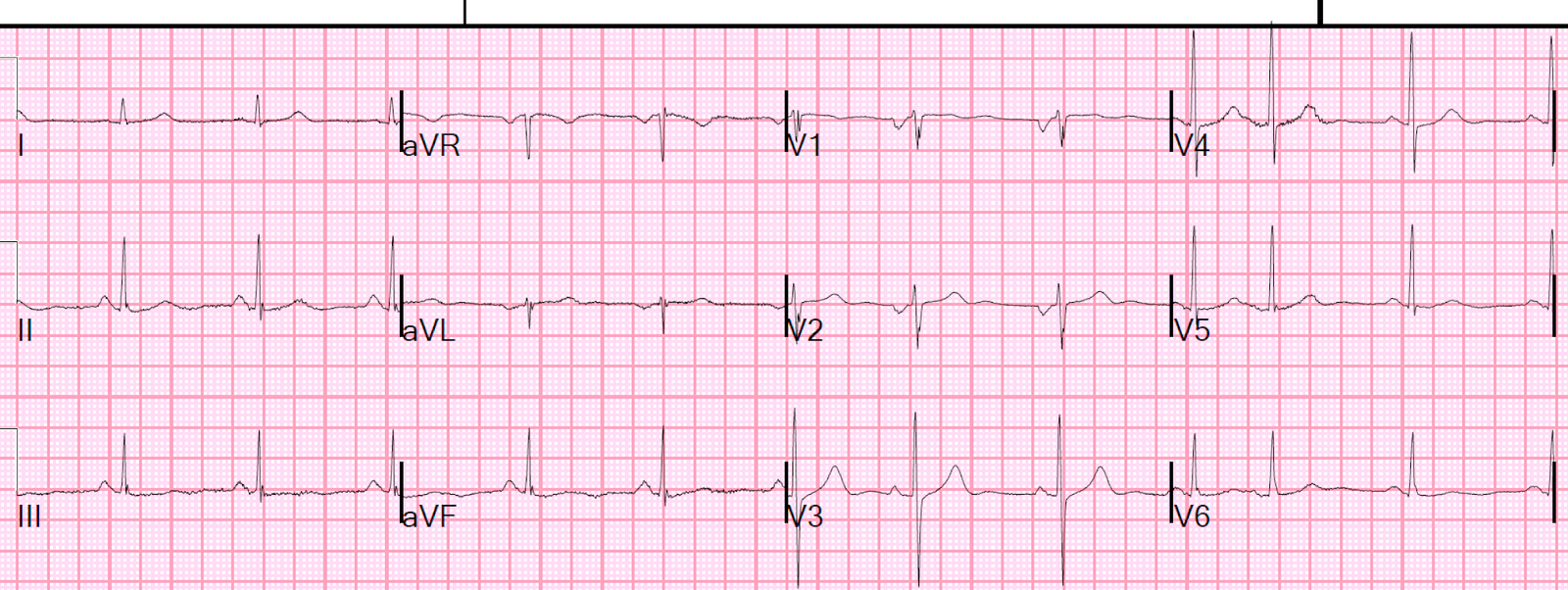

If a patient demonstrates this EKG finding despite fixing their oxygenation, hypotension,

tachyarrhythmia, etc. and this finding persists on EKG it may be indicative of left main or

severe triple vessel disease. However, until all of the other physiologic derangements

are fixed, this is a non-specific finding that merely demonstrates diffuse subendocardial

ischemia.

Imagine if the patient had been given aspirin and heparin for NonSTEMI!

See some of our other related posts:

ST Elevation in Lead aVR, with diffuse ST depression, does not represent left main

occlusion

Global ST depression with ST elevation in aVR – what is the cause?

A man in his 50s with witnessed arrest and ST elevation in aVR

Chest pain, pelvic and abdominal pain, hypotension, and severe ischemia on the ECG

How does acute left main occlusion present on the ECG?

Can you see through this wide complex rhythm?

The 4 Physiologic Etiologies of Shock, and the 3 Etiologies of Cardiogenic Shock

An elderly man with sudden cardiogenic shock, diffuse ST depressions, and STE in aVR

The below comes from this post:

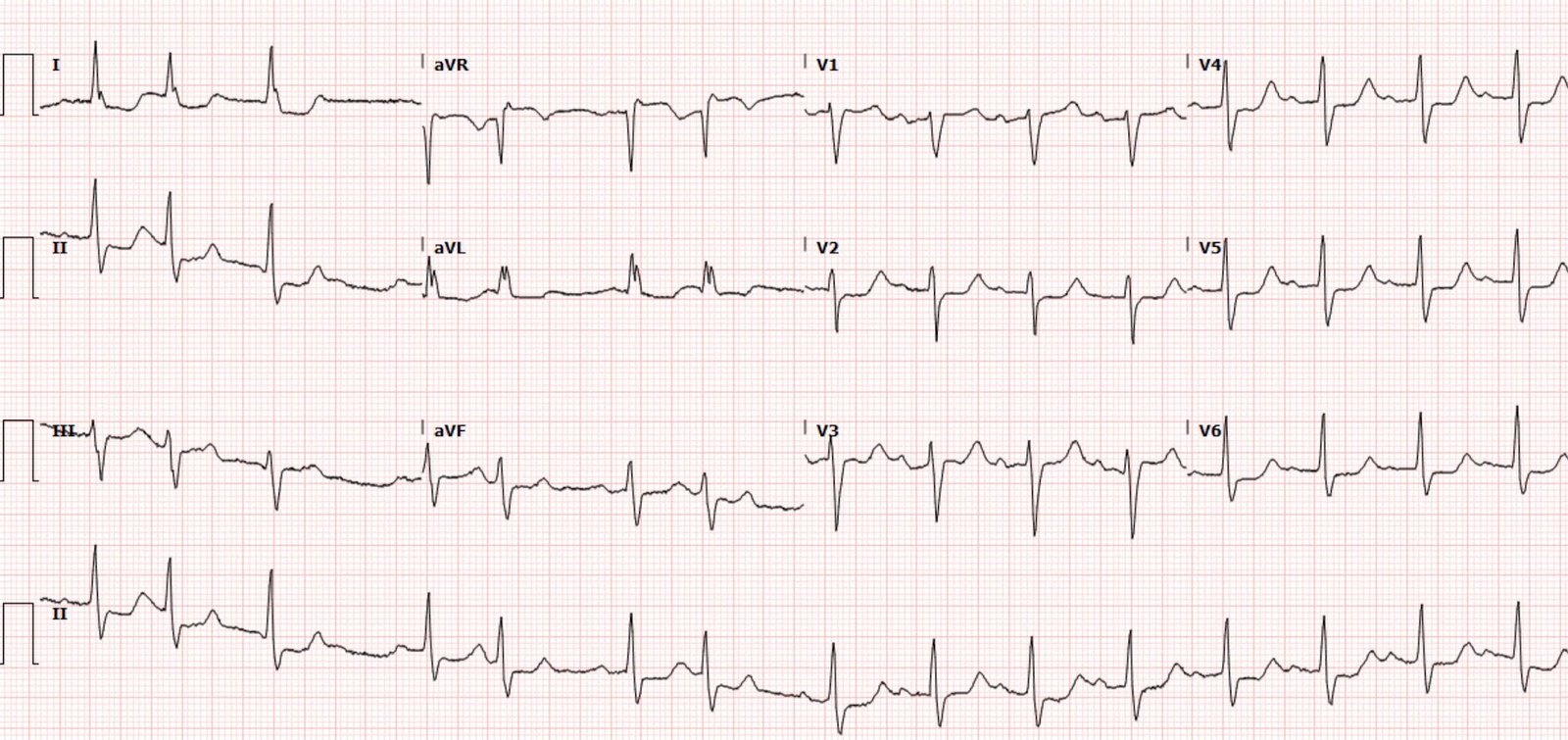

Extreme widespread ST depression, with ST Elevation in aVR. What do you think?

Learning point

Most widespread ST depression, with STE in aVR is NOT due to ACS. See 2 papers referenced below.

The differential diagnosis for widespread ST depression with STE in aVR is anything that can cause supply demand mismatch. So anything that Some important ones are listed here:

1. Valvular disease

2. Severe anemia

3. Severe hypoxia

4. Hypotension, especially diastolic hypotension

5. Hemoglobinopathies or cellular toxins

6. Severe LVH or HOCM, which prevents adequate perfusion

7. Extreme tachycardia

8. Extreme hypertension

9. Lesser degrees of any of the above, if combined with fixed coronary stenoses.

Acute coronary syndrome. Severe Left Main stenosis (not occlusion!) or LAD, or single vessel ACS with 3 vessel disease.

The ECG does not differentiate the above etiologies, it simply signifies that there is severe diffuse global supply-demand mismatch, whatever the etiology.

LVH, LBBB, RBBB, and RVH may manifest ST depression without any ischemia!

Other cases:

2 cases of Aortic Stenosis:

Diffuse Subendocardial Ischemia on the ECG. Left main? 3-vessel disease? No!

An elderly man with sudden cardiogenic shock, diffuse ST depressions, and STE in aVR

Literature

1. Knotts et al. found that such ECG findings (STE in aVR) only represented left main ACS in 14% of such ECGs:

Only 23% of patients with the aVR STE pattern had any LM disease (fewer if defined as ≥ 50% stenosis). Only 28% of patients had ACS of any vessel, and, of those patients, the LM was the culprit in just 49% (14% of all cases). It was a baseline finding in 62% of patients, usually due to LVH.

Reference: Knotts RJ, Wilson JM, Kim E, Huang HD, Birnbaum Y. Diffuse ST depression with ST elevation in aVR: Is this pattern specific for global ischemia due to left main coronary artery disease? J Electrocardiol 2013;46:240-8.

2. Now there is a paper published in 2019 that proves the point beyond doubt, though makes it clear that this pattern is associated with very high mortality.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S000293431930049X

Harhash AA et al. aVR ST Segment Elevation: Acute STEMI or Not? Incidence of an Acute Coronary Occlusion. American Journal of Medicine 132(5):622-630; May 2019.

Here is the abstract:

Background

Identification of ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is critical because early reperfusion can save myocardium and increase survival. ST elevation (STE) in lead augmented vector right (aVR), coexistent with multilead ST depression, was endorsed as a sign of acute occlusion of the left main or proximal left anterior descending coronary artery in the 2013 STEMI guidelines. We investigated the incidence of an acutely occluded coronary in patients presenting with STE-aVR with multi-lead ST depression.

Methods

STEMI activations between January 2014 and April 2018 at the University of Arizona Medical Center were identified. All electrocardiograms (ECGs) and coronary angiograms were blindly analyzed by experienced cardiologists. Among 847 STEMI activations, 99 patients (12%) were identified with STE-aVR with multi-lead ST depression.

Smith comment: this is a very limited population, as it only includes those with STEMI activations. There are likely many other patients with STE-aVR who did not get a STEMI activation as they were not suspected of having ACS.

Results

Emergent angiography was performed in 80% (79/99) of patients. Thirty-six patients (36%) presented with cardiac arrest, and 78% (28/36) underwent emergent angiography. Coronary occlusion, thought to be culprit, was identified in only 8 patients (10%), and none of those lesions were left main or left anterior descending occlusions. A total of 47 patients (59%) were found to have severe coronary disease, but most had intact distal flow. Thirty-two patients (40%) had mild to moderate or no significant disease. However, STE-aVR with multilead ST depression was associated with 31% in-hospital mortality compared with only 6.2% in a subgroup of 190 patients with STEMI without STE-aVR (p less than 0.00001).

Comment: Again, this does not include the many STE-aVR patients who were not activated, so even fewer would have ACS, and mortality in this group is much greater than in all STE-aVR patients.

Conclusions

STE-aVR with multilead ST depression was associated with acutely thrombotic coronary occlusion in only 10% of patients. Routine STEMI activation in STE-aVR for emergent revascularization is not warranted, although urgent, rather than emergent, catheterization appears to be important.